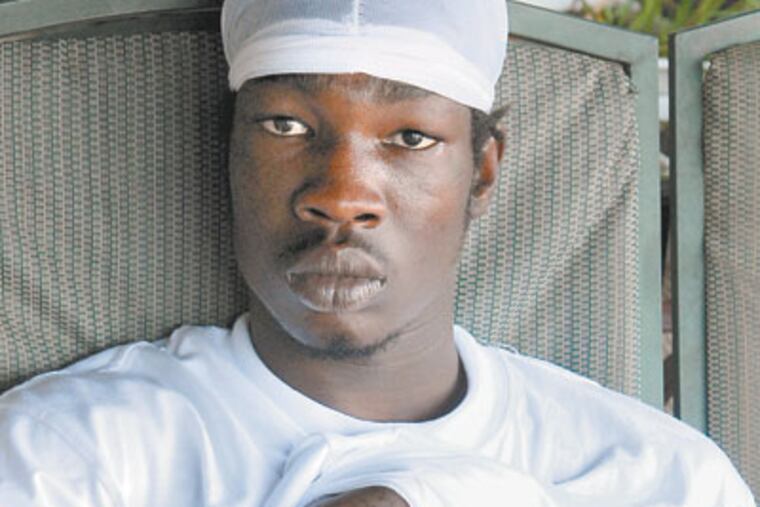

A life on the street: Leroy Lewis

First of two parts. Forty-three minutes past midnight, a crackle pierced the summer air. For a moment, Leroy Lewis, perched on a concrete wall beside a rowhouse in his Juniata Park neighborhood, talking to two friends, dismissed the sound as leftover fireworks.

First of two parts.

Forty-three minutes past midnight, a crackle pierced the summer air. For a moment, Leroy Lewis, perched on a concrete wall beside a rowhouse in his Juniata Park neighborhood, talking to two friends, dismissed the sound as leftover fireworks.

When Lewis, 19, turned to look, he saw a young man, his baseball cap tilted low, moving from the alleyway across the narrow street, pointing a gun, hunting.

"The next shot was me looking at him," Lewis recounted later. "I just seen a whole bunch of fire."

Lewis took off, dipping behind parked cars, as bullets cut through his stomach, his buttocks, an ankle, a shoulder, and a thigh. His friends were also hit, one in the chest, the other in a thigh.

As Lewis collapsed a block away on some rowhouse steps, shot six times, one thought filled his mind: "I'm going to die."

Hours later, as chief trauma surgeon Amy Goldberg scanned the list of patients rushed into Temple University Hospital's emergency room overnight on July 9, 2008, one name stood out.

"Not again," Goldberg thought.

Ten months before, on Sept. 1, 2007, she had stitched and stapled together Lewis' stomach, ripped open by a bullet.

Goldberg, 48, remembered how Lewis had worked hard to recover, in the hospital for weeks, visiting the trauma clinic for months, calling her Miss Amy. Lewis admitted to hospital staff that he'd sold drugs, on and off. But unlike many gunshot patients - brooding, itching to get back to the street - Lewis, then 18, said he wanted to change

Now here he was again. Goldberg, who had completed her residency at Temple 16 years earlier, couldn't help but wonder, "How long before he is lost for good?"

Three perilous ages

It is a haunting question about one of Philadelphia's most exhaustive, expensive, frustrating, and mournful problems:

From 2004 through 2008, 8,314 shootings in the city produced victims. Of the victims, 623 were 19-year-olds, more than any other age group. Add 18- and 20-year-olds - 1,071 more victims - and those in this three-year bridge to adulthood were 17 times more likely than other Philadelphians to be shot.

Eighty-four percent of the 18-, 19- and 20-year-old gunshot victims were African American males.

Why is this age group most at risk?

"I don't know if anyone has the answer yet," said Sam Gulino, the city's chief medical examiner, who is conducting a study of 15 years of youth homicide data.

"From a commonsense standpoint, it's the first time kids are out of school, so a large portion of their time is not structured by activities. If you have a 17-year-old who is cutting school, there's the school or DHS to intervene. When you're 19, none of that stuff exists."

When he was 19, the voids in Lewis' life were daunting but not uncommon: a single-mother home, a dismal education, little job experience, self-doubt, a lack of motivation, a need to take care of himself and be respected as a man, and his frustration of not knowing how.

"Some of these guys don't know how to catch a bus out of their neighborhood," said Darryl Coates, executive director of the nonprofit Philadelphia Anti-Drug/Anti-Violence Network. "And when they walk out the door, and guns, drugs and violence are all they see, and are exposed to, what do we expect? We have to show our young people there's all these opportunities out there, and what they look like."

Most programs focus on juveniles in the city's Department of Human Servies system or young probationers. But "to meet the needs of this 19-year-old who's on the cusp," said Deputy Mayor of Public Safety Everett Gillison, "the only programs right now are few and far between. This is the hardest nut to crack."

On Lewis' path to adulthood, he made his choices often marred by an impatient temper. He became a delinquent and a drug dealer, a kid easy to write off.

"A lot of people aren't going to give this young man sympathy," said sociologist Elijah Anderson.

Anderson, a Philadelphia native, an author, and a Yale University professor, has studied black urban culture in the city for three decades.

"A lot of that has to do with the fact that the young black male, what he represents as a stereotype, is an alienating figure. People want to blame him for what's happening."

The bottom line, said Scott Charles, trauma outreach coordinator at Temple University Hospital, is "we can moralize it all we want. But if we don't change his circumstances so he can be more stable, there's nothing to make him less likely to come back to us."

"The violence," Charles said, "can stop here if we give him the tools that he needs. If not, violence in the city is going to increase exponentially."

What happened to Lewis between the ages of 18 and 20 - shot twice in less than a year, careening between life as a man-child and as a corner drug hustler - reveals the battle young men like him, without discernible skills, face in navigating their futures. For some, outcomes are predictable. They end up dead, or in jail. For Lewis, no one could predict the troubles to come.

Trauma of being shot

While Lewis lay in a hospital bed in July 2008, a chest tube helping him breathe, Charles phoned Doris Spears, the case-management supervisor of PIRIS, the Pennsylvania Injury Reporting and Intervention System, to tell her that Lewis had been shot a second time.

PIRIS, a pilot initiative, began in April 2006. With a $1.3 million budget, the program aimed to catch gunshot victims ages 15 to 24 when they were most apt to listen: while in a hospital bed.

At three hospitals, outreach workers like Charles referred patients to the program, run out of a Center City office. Once enrolled, gunshot victims were guided by case managers through a labyrinth of social services to help prevent them from being struck by gun violence again. More than half of those in the program, PIRIS data found, had left high school without a diploma, and 67 percent were unemployed when they were shot.

Surviving a bullet can be a time to rebuild a life - or a prelude to more violence. After surgeons like Goldberg stitch them back together, many patients return to the neighborhoods, friends, and lifestyles that got them shot in the first place. Mental-health experts say many of these walking wounded suffer the same mental distress as combat veterans in Iraq and Afghanistan, stress that often goes unchecked and untreated.

In fact, "most people who have been shot develop post-traumatic stress disorder," said Paul Fink, a psychiatry professor at Temple University's School of Medicine and chairman of the city's youth homicide committee. "Being shot is a real trauma, and people have a great deal of difficulty overcoming it."

Feelings of fear and helplessness become barriers to finding a job or returning to school, he said. Anger fuels the urge to retaliate, the need to return to the neighborhood bigger and badder. Gunshot victims struggle "with the idea that you're going to be killed, that you're going to be shot again, that your life is over," Fink said.

The first time Charles referred Lewis to PIRIS in September 2007, after he'd been shot in the stomach, Lewis rejected the program. Frustrated that after weeks he hadn't connected with a case manager, Lewis demanded that Charles rip up his PIRIS paperwork. Lewis refused to reconsider. It was the same self-defeating behavior that Charles had seen in gunshot patients many times before.

"You can't expect him to get motivated if he doesn't know what direction to run in," Charles said. "He needs more than a job. He needs someone to help him with adulthood."

Ten months later, Charles updated Spears, PIRIS' case-management supervisor. Lewis was back in the ER, he told her, shot six times. Goldberg, the trauma surgeon, 5-foot-2 with dark, spiky hair, stood nearby, listening to Charles' half of the conversation. At one point, overcome with concern, she leaned over and yelled into the phone: "You're taking him!"

Three days later - with a tenuous reconnection to PIRIS in place - Lewis was discharged.

'It's about the block'

A month later, on a warm afternoon in early August 2008, Lewis sat hunched on the tan sofa in his mother's living room, accented with family photographs and African art.

Sunlight peeked through the drawn curtains, beyond which lie the tree-lined streets and redbrick houses of Juniata Park, a diverse, working-class community north of Kensington.

"I don't like to be seen outside," Lewis said, swatting his sister's orange kitten with his socked feet.

Lewis, a lean 5-11, wore a billowy white T-shirt and blue jeans. A white do-rag covered his short dreadlocks. A tattoo on his right hand read "Black," his nickname on the street for his mahogany skin.

With his mother at her job as an aide at a nursing home, and his younger siblings away for the summer or at day care, Lewis spent most of his time in his room, watching BET, listening to the Notorious B.I.G. or Lil Wayne, or sleeping, waiting for his life to take a turn.

As he opened up to a reporter, he leaned in, his brown eyes cast toward the floor. He spoke in polite tones, and sometimes displayed the grin of a shy, awkward teen.

Since he was 16, when he managed to graduate from high school, Lewis said, he'd dealt drugs on and off. Standing not far from his home, in an alley overlooking neighbors' kitchens and back bedrooms, he sold crack, marijuana, and pills. He wouldn't discuss the source of the drugs he sold, sticking to a no-snitching code, telling his story and no one else's. But it was clear from what he said that he had been a vendor, not a supplier. He described his world then: "Doing dumb stuff, like what regular teenagers do. Buyin' a whole bunch of clothes and sneaks, drinkin', and smokin' " weed.

The shootings, 10 months apart, had little to do with other, he said.

"It's about the block," he explained. "They try to get the money I have."

The shooting in September 2007 was over a debt, he said. Lewis was walking to the corner deli with a girl when he ran into a drug dealer who owed him money.

Lewis couldn't remember how much, maybe $100. More so, he wanted the respect the debt had cost him. "What's up?" Lewis demanded. The 18-year-old blew him off.

Nights later, when they saw each other on the north side of Hunting Park Avenue, insults were exchanged, and a fight erupted outside a neighbor's home. As the two wrestled to the ground, Lewis said, he felt a "real hard punch" as a bullet burrowed into his abdomen. A bystander had shot him in the stomach.

The police report reveals only the barest facts: "Complainant was shot at the above location and transported to Temple hospital by private auto. Complainant received a gun shot wound to the stomach. Complainant is in critical condition. . . . There are no known witnesses. . . ."

Wounded, riding in a friend's dark sedan, Lewis said, he felt his body growing warm. Vomiting, writhing in pain, he screamed to Temple ER doctors: "Get this out of me." After surgery, an infection required his incision to remain open for weeks, leaving a gaping wound. The shooting and the entire ordeal are indelibly marked by a jagged scar from his sternum to his navel.

What led to the second shooting is harder to discern. That July night in 2008, Lewis stood in the alley where he dealt drugs, hunched over a pile of money in a dice game. He had cleaned up, and as the players dispersed, he gave one pouter a $20 consolation. The teen handed it back, using the money to buy a "couple of jays," from him, Lewis said.

He left but returned moments later, this time looking for "wet," marijuana dipped in embalming fluid. "I don't have it," Lewis said he had told him, "but I know where I can get it."

Lewis phoned someone and placed the order. While they waited in the alley, on the side of a rowhouse, 43 minutes after midnight - Lewis thinks the whole thing may have been a setup - someone opened fire. The shooter's rage may have come from the dice game, or an argument over a smacked cigarette two weeks before, or the constant eruptions over who controlled the alley's trade. No one knows anymore.

The six shots, marked by nine dime-size bullet wounds, have left Lewis with a limp; his left foot shattered, achy, and weak; and lingering thoughts of betrayal.

Now the prisoner of his own living room, he was tired of the block, tired of a life going nowhere. He wanted a job, he said, and the chance to study business at community college so he could go into real estate like his grandfather in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he had grown up.

A few days earlier, Lewis had shared these goals with PIRIS case manager Tinisha Scott. Scott, 28, saddled with 10 other clients, said she'd return in a week to develop a plan, leaving Lewis somewhat encouraged.

He did not have a driver's license, and he'd held only one job, housekeeping part time at the nursing home where his mother works.

"I don't really believe nothing until I see it," Lewis said. "But I'm just thinking and hoping I could be able to pursue what I want to do with their help. I truly don't wanna be outside."

Surviving gunfire twice, he felt like a marked man.

According to police records, no one was arrested in the first shooting. Lewis figured that when his assailant got out of jail - he was incarcerated for another crime - "we can just settle it like men," Lewis had assured guys in the neighborhood. "Rumble in the street in front of everybody if need be."

In the second shooting, the 18-year-old arrested by police was not convicted. None of the witnesses, including Lewis, bothered to come forward. But that wasn't why Lewis was afraid. He believed neighborhood rivals and wannabes would view his death as a prize, like winning a giant teddy bear at a fair.

"There's just so much hatred," Lewis said of the streets. "They gonna look at me like, 'Who do he think he is?' and they gonna try."

Whether Lewis was being pursued by hooded gunmen, or paranoia, remained to be seen.

As Lewis talked, his cell phone rang often, his mother, calling from her job, checking, worrying.

"Hi, Mommy," he answered.

"OK, Mommy," peppered his conversation, and for the moment, Lewis sounded like a little boy.

After he hung up, he explained: "She scared. She scared for my life out here like I'm scared for my life out here. She feels as though it's not going to be no third chance."

Growing up in Brooklyn

Lewis remembered his mother, Paulette Lewis, raising four little boys on her own, rarely let them play outside their three-bedroom apartment in a Brooklyn rowhouse his grandfather owned.

The family was close-knit, and every night, Lewis said, nodding for emphasis, members gathered at his grandparents' nearby home for Bible study.

His grandfather, a doorman most of his life, was a deacon at First Born Assembly Pentecostal church. Lewis described him as a man of quiet strength "who doesn't talk, who's about doing." His grandmother led prayer meetings.

In raising her boys, his mother didn't spare the rod, Lewis said. "Oh, Ma Dukes didn't play," he snickered, using his nickname for her.

His mother worked as a health aide when she could, caring for elderly people in their homes. Around their basement apartment, money was tight.

Lewis, the third oldest, the chatterbox, loved hearing his mother read to him. He has little memory of his father - his spitting image, relatives like to tell him. From his mother, he has pieced together the story of a man who ran the streets, courted trouble, and got deported to Jamaica when Lewis was 3.

About three years later, his mother's boyfriend, a childhood friend, Cecil Waldron, moved in, and came to know Lewis as a good kid who had "a lot of pent-up frustration."

Looking back, Lewis believes that growing up without a father, the rigidness of Bible study every night, the lack of material things, and the constant punching matches with his brothers all touched him.

When he acted up in school or disobeyed his mother at home, where she would dismiss him as "hardheaded" or "just like your father," Waldron pulled him aside, trying to offer discipline and direction.

"They were looking for a father," Waldron said. "They wanted a father."

Waldron, who worked in a nursing-home laundry, bought Lewis and his brothers clothes, took them to the park to play and ride bikes, and sat with them at the kitchen table for homework. "As long as the schoolwork is done," he'd tell them, "you're going to get what you deserve."

Remembering Waldron, Lewis said: "He did more for me than a father would. He gave me boundaries."

A broken family

But when Lewis was 10, Waldron and his mother broke up. She moved to Philadelphia to stay with an aunt, bringing with her Lewis, his younger brother, and the baby girl she'd had with Waldron. Lewis' two older brothers stayed in Brooklyn with their grandparents.

"Once I came to Philly, everything just went downhill for me," Lewis said. He missed his brothers, his grandparents, everything he had in Brooklyn.

The family moved twice, with Lewis attending two different schools. With each move, he became more disruptive. By sixth grade, he had settled into Benjamin Rush Middle School in Northeast Philadelphia, where he struggled with math.

"I just couldn't get it, and I figured if I couldn't get it, no one was," he recalled with a chuckle.

In math class, Lewis threw paper balls, talked back, talked to everyone. He enjoyed the attention, the tough-guy reputation he earned in fights.

It all ended one afternoon in the hall, in a scuffle between Lewis and a math teacher over a basketball. The teacher said Lewis had hit him, which Lewis denies.

School officials acted swiftly, and Lewis' days of disrupting classes at Benjamin Rush Middle School were over.

A family court judge ordered him to Stillmeadow Inc., a now-closed juvenile residential facility north of Scranton, the first in a chain of alternative schools that would make up most of the rest of his education.

"I thought it would have been good for him," his mother said, looking back. "What I saw, he got worse."

Shallcross, a disciplinary school in Northeast Philadelphia, was next. During his year there, Lewis said, he was constantly suspended for fighting and upsetting class until he "got kicked out." So in the fall of 2003, his mother sent him to his grandparents in Brooklyn, to live under his grandfather's biblical lessons, hard work ethic, and stern gaze.

Lewis, then 14, welcomed the return. As for his grandfather, Essert Cameron, he said he had wanted "to see if I could make something out of him."

His grandfather enrolled Lewis in Samuel Tilden High School, and gave him chores: Take out the garbage, mop the floors, clean the yard.

One Saturday, seeing his brother and cousin enjoying television while he worked, Lewis complained: "Why is everything me?"

"That just turned me off completely," his grandfather said. On top of it, his grandfather learned that Lewis, still struggling with math, was skipping classes to hang out with his friends.

"I wanted him to have good friends," his grandfather said. "Friends that would help him, not drag him down. But he didn't listen."

After the school year, he sent his grandson back to Philadelphia to his mother.

A graduate at 16

In June 2005, at a Community Education Partners-run disciplinary school, Lewis learned that, with his New York credits, he had enough to graduate. He was 16.

At his tiny ceremony, in a dull auditorium, he and seven other students marched to the stage in black caps and gowns while relatives looked on from folding chairs.

"It felt good," Lewis reminisced. "I felt like, 'Wow.' "

Out of school, with no job experience and college just a distant concept, Lewis hung out in the neighborhood as the summer waned. He soon met up with a friend from disciplinary school. The two had promised to meet up when they were released - "kick it on the outside," Lewis said.

The summer was a constant state of recess: on corners, hanging with friends, cracking jokes, drinking beer, smoking marijuana, and flirting with girls, late into the night. Some friends flashed their drug money. Others let Lewis and his friend watch the pace of the drug game firsthand, the ease and the speed in which that money was made. Lewis and his friend saw opportunity, and before long the two started selling crack cocaine together.

Lewis found he could pocket as much as $600 a day.

"It was all she wrote after that," he said. "I didn't want to go to school. I didn't want a job. I didn't want to work for nobody. I wanted to get my own money."

He also felt the fraternity of hanging with "my boys," some friends already selling drugs.

"It's like they're with you," Lewis said. "And the girls come around, and the cars. It's like a family."

Lewis treated his friends to dinners at Red Lobster, drinks at neighborhood bars, and road trips to Baltimore's Inner Harbor; he indulged himself in trendy clothes, expensive sneakers, and a dirt bike - things once out of his reach.

Disgusted, his mother gave him an ultimatum: Stop selling drugs or leave the house.

Lewis left.

"I pretty much stayed on the streets," he said, working a corner of the alley, overshadowed by a bustling commercial street, from early morning until the dark hours of night. "It was addictive money," he said. "I wasn't too much worried about the consequences. I was just getting money."

Lewis would pop into a friend's home to grab a bite, wash up, and change clothes, then return to his corner. The fast money lasted for months, he said, until police busted him for drug possession. A family court judge sent him six hours away to VisionQuest in northwest Pennsylvania, a program geared to troubled youths, which Lewis called "boot camp."

"It felt like a vacation to me," he said.

He enjoyed the drills, the cadences, and the horseback rides. But "guys were always trying to push you." Fights erupted over stares, bumps, cigarettes.

One day in late December, in the break room, Lewis and some guys were sitting around the television while another group played pool, trash talking, laughing, and sinking balls.

"Quiet the f- down," Lewis said he had yelled.

"Nah, we ain't quieting down," a pool player fired back. "Turn the TV up."

That was it.

On his feet, Lewis asserted, "You can see me in my room." He was prepared to settle the silly disagreement with his fists, as he had so many times before. If he let this guy punk him, he felt, others would rush to follow.

A brawl ensued. According to Venango County Court records, Lewis and two other males jumped the pool player, splitting his lip.

Lewis pleaded guilty to simple assault, and was sentenced to six to 231/2 months of probation. It was a month after his 18th birthday; it was his first adult record.

Back home in 2007, and sick of the block, sick of the cops and the stickup boys, sick of his mother in his ear, sick of a life going nowhere, Lewis got his first and only job: housekeeping at the nursing home where his mother worked.

A month later, trying to collect an old drug debt, he was shot in the stomach, his first encounter with Goldberg and Charles at Temple University Hospital. After Lewis gave up on PIRIS, he went back to selling drugs on the block.

"I was just so down and hurt," he recalled. "I just didn't care anymore."

Ten months later, standing in the alley where he dealt drugs, his dice game winnings in his pocket, he was shot again, six shots that left multiple wounds.

Tomorrow

Leroy Lewis longs for success but must deal with more violence on the streets, and with his own paranoia.