New clues emerge in 1970 Boy Scout murder, but it's still a mystery

IT WAS THE SPRING of 1970. Suburbia was unraveling. Parents hovered over their children. Catholic schoolboys had become central characters in a real-life whodunit that stretched from Philadelphia to Phoenixville. It felt like everyone was a suspect.

IT WAS THE SPRING of 1970. Suburbia was unraveling.

Parents hovered over their children. Catholic schoolboys had become central characters in a real-life whodunit that stretched from Philadelphia to Phoenixville. It felt like everyone was a suspect.

One by one, Boy Scouts in Darby Borough were hooked up to polygraph machines and interrogated. Their knives were confiscated and sent to a forensics lab to be examined for blood residue.

Crime-scene investigators drained the pond outside St. Basil the Great Church, about 30 miles away in Chester County. They swept the church's triangle-shaped property with metal detectors, again and again, searching for the murder weapon.

Hundreds of people were interviewed, and each Sunday around sunrise, police set up a checkpoint near the church to ask drivers if they'd seen anything unusual the morning of April 26, 1970, when 11-year-old Terry Bowers was killed in his sleeping bag while camping out with Boy Scout Troop 275 from Darby's Blessed Virgin Mary parish.

"I thought it was the safest place in God's green pastures," one Scout's father told the Philadelphia Bulletin at Bowers' viewing.

Police eyed mentally ill patients from nearby hospitals, and one investigator approached even the kids' priest, discreetly suggesting that maybe Bowers' fellow Scouts or their leaders might be more forthcoming when they confessed their sins in church. The Boy Scouts posted a $5,000 reward for information about the "dastardly crime."

No witnesses, weapon or motive. No arrests.

But, more than four decades later, new theories are emerging about one of suburban Philadelphia's most bizarre unsolved murders - and Boy Scout records indicate that a former Scout and convicted rapist once admitted to killing Bowers in retaliation for being kicked out of the Scouts.

"How did this happen? How does a boy get stabbed to death on the grounds of a Catholic church on a Boy Scout trip and nobody hears anything?" Bowers' sister, Maureen, who was 12 when Terry was killed, asked last week. "The poor little guy came home in a body bag."

Town in mourning

Lorraine DeLuca Placido remembers jumping rope in front of her family's rowhouse on Winthrop Road that Sunday when a girl next door said Terry Bowers was dead. Placido was 9 years old, two grades below him.

"By the end of the night, everyone in the neighborhood was talking about it," said Placido, now director of the physician-liaison program at Penn Medicine.

Placido began researching the case in 1994, hoping to find something police missed. Her binder is full of meticulous notes and dozens of news stories.

"Making a diagnosis and solving a crime is the same thing. You have to find the clues," she said. "My mind just works that way."

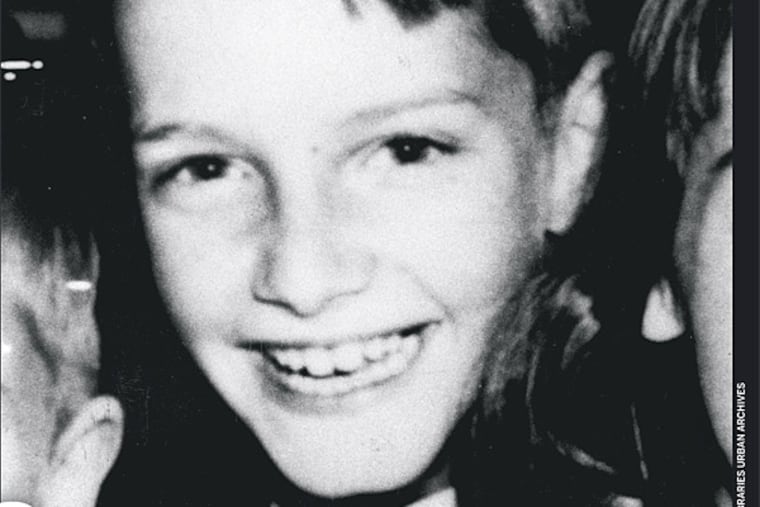

The local newspapers, which estimated that 1,500 people attended Bowers' viewing, described him as a typical sixth-grader. He played Little League and kept a pet snake in a box on the porch, but also worked for $2 a day at his grandmother's gas station, putting the money toward his Scout uniform - and a $2,500 Boy Scout insurance policy that ended up paying for his own funeral.

He was 4 feet 7. About 80 pounds. Blond hair.

"It didn't happen to just the Bowers family; it happened to the whole town of Darby," said Maureen Bowers, who was in her brother's grade at BVM. "I have classmates who said it robbed them of their childhood. People were afraid for their children.

"We fought, we played, we got in trouble together. We had a lot in common. And then he was gone."

Police said that Bowers had been stabbed four times with a small blade about 6:30 a.m. He was in his green sleeping bag while camping in an open field - about 200 yards from the church buildings - with 29 other members of his troop. His body was discovered about an hour later.

The investigation was hexed from the beginning. By the time State Police Sgt. James Wenner arrived, the body had been moved and parents were on the scene.

"It was just a hell of a situation," Wenner, the case's lead investigator, said last week from his Lancaster home. "Damn near every Boy Scout has got a knife."

The autopsy showed no signs of sexual abuse or drugs in Bowers' system. One driver later reported seeing a vehicle by the campsite that morning, but couldn't provide a description, not even a color.

Murder theories abounded: Was it a random killer who wandered onto the field before dawn? One of the Scouts? The janitor at the church? A pedophile priest? Was there a sexual relationship within the group that Terry found out about? Was it preplanned? Was his body moved? Why wouldn't he yell?

"It might have been bigger than we'll ever know, and it was worth killing a kid to shut him up," Placido said.

In 1972, police questioned a man who had newspaper clippings of the Bowers case in his Center City apartment. In the early 1980s, the investigation was revived when an inmate reportedly claimed to have information about the case. Both leads fizzled out.

"I often regret not putting someone in jail for it," said Wenner, 85, whose oldest son was Terry's age at the time of the murder. "We ran everyone imaginable connected with the case on the polygraph. It never went anyplace."

Terry's father, Terrence Sr., a mechanic, died of a massive heart attack in 1978 at age 47. Wenner retired the following year. Terry's mother, Mary, kept digging, calling investigators, writing to the TV program "Unsolved Mysteries," contemplating whether a psychic could help.

"It literally killed this man, and my mother hasn't done well since," Maureen Bowers said. "This punched a hole in our world and destroyed our mother."

Break in the case?

Someone, however, did confess to killing Terry Bowers, according to the Boy Scouts' so-called "perversion files," which listed pedophiles and others that the Scouts wanted to keep out of the organization.

The trove of recently released documents includes letters that a Boy Scout official wrote in 1971 referring to Lawrence Wakely, a former Scout now serving time at a state prison in Huntingdon. Wakely told police he killed Bowers because he had been kicked out of the Scouts, according to the letter from the Boy Scouts official.

The confession doesn't appear to have been reported in the news at the time. But Wenner said last week that he'd interviewed a man 40 years ago who fits Wakely's description. Wenner said that Wakely's story didn't check out and that he failed a lie-detector test. A state trooper who reviewed the file said Wakely had been dismissed as a suspect.

"Mentally, he wasn't on top of things," Wenner said. "He didn't have the right answers to the nitty gritty of the investigation, things that only the guy who did it would have known."

Placido also discovered that a former police chief, now a registered sex offender living in Philadelphia, had mysteriously showed up at Bowers' autopsy, even though his police department was 20 miles away from the crime scene. But the ex-chief told the Daily News last week that he was only at the coroner's office to meet a doctor. The coroner at the time confirmed that the doctor was there.

Two more dead ends, it seems.

"It pisses you off. Every once in a while, I'll pull everything out and say, 'Did I miss something?'" Placido said.

'Anything is possible'

When the Catholic sex-abuse scandal broke in 2002, Chris Bowers immediately thought of his brother's death. Could it have been a priest?

"If they wanted to find out where a bunch of young boys were hanging out, they were privy to that information," said Bowers, 52, who has a tattoo of his brother's face on his bicep. "These are some of the biggest organizations in the world," he said of the Roman Catholic Church and the Boy Scouts. "If they wanted this thing shut down, they'd shut it down real fast. I think they did. But if this happened today, it would have been solved."

It's just speculation, and after 42 years of far-fetched theories, the Bowers family wants answers.

"I'd like to give my mother some closure in this lifetime. It haunts her every day," Maureen Bowers said.

She suspects that someone from Troop 275 knows something.

"They were scared little boys then who are men now with children of their own. They might say, 'Yeah, I did hear something or see something,'" Maureen Bowers said. "Anything is possible."

Placido had once considered using her voluminous binder of notes and news clippings to write a book about the case. She can't bring herself to do it, though. Not yet.

"A book has a beginning, middle and end," she said. "Until the murder is solved, there is no end."