Collection of postcards captures Phila.'s changes

The federal government says a new designation as a "Promise Zone" holds the possibility of transforming a big, ailing chunk of West Philadelphia.

The federal government says a new designation as a "Promise Zone" holds the possibility of transforming a big, ailing chunk of West Philadelphia.

Robert Morris Skaler can remember when the area didn't need a zone to have promise.

He was born there, grew up there, and forever after remained interested in the place and its potential.

As a boy, he lived on the boundary of Mantua and Belmont, an area that in the 1940s held not just a healthy middle-class population but something that to him was more intriguing: a stock of big Victorian and Italianate houses, the envy of any in Philadelphia.

When Skaler walked home from the Belmont School, he'd pass grand, 70-year-old houses that were turning run-down. He would wonder, "What did they look like when they were new?"

In trying to answer that question, he compiled a remarkable one-man archive: an estimated 35,000 postcards of Philadelphia streets, scenes, and buildings, about 10 percent of them centered on the area that's now the focus of government attention.

"I was always looking for my house," said the 78-year-old architect and historian, "and never found it."

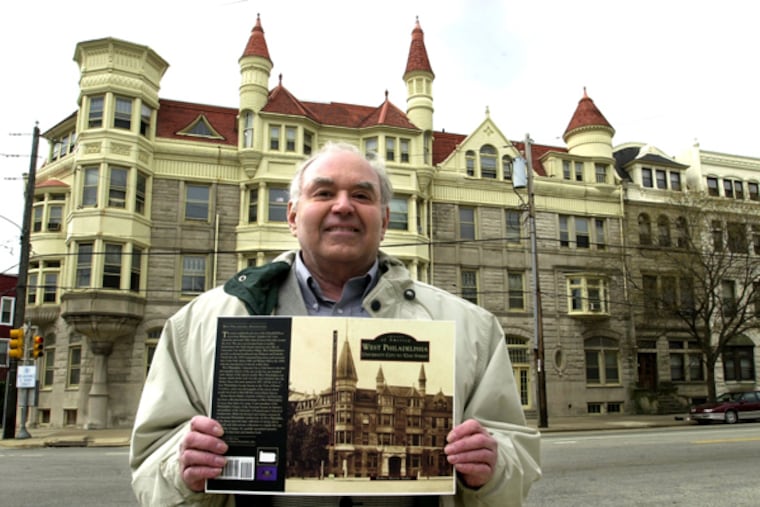

Skaler has written books on West Philadelphia, Broad Street, Rittenhouse Square, and Society Hill, served as head of the Philadelphia chapter of the Victorian Society, and today runs a forensic-architecture firm from his home in Cheltenham.

But his passion for postcards has helped preserve a place that exists only in the old bones of its surviving buildings.

Some favorites:

A postcard showing the lavish interior of Furey's, a sweets shop at 42d Street and Lancaster Avenue. Another showing a row of wooden houses near 42d and Ogden Street, their picket fences making the street look like suburbia. Any of the shots of the huge stone churches that once dominated the area.

"So much has been lost," Skaler said.

For decades, Mantua and its environs have been punished by decline and demolition. Within the Promise Zone, nearly 15 percent of the houses are vacant, double the city average.

Empty lots are everywhere. In places, half the street is gone.

Now the government plans a reclamation effort. This month, the White House announced that West Philadelphia would get more attention as one of five Promise Zones nationwide.

The immediate impact will be minimal. The Obama administration offers no money to hire police, build houses, or add teachers to schools. Instead, it promises to award bonus points in competitions for aid, giving the area a better chance to win government funds.

What the White House most promises is to take notice - and to offer help and advice when it can.

The zone covers all of Mantua and all or part of Powelton, West Powelton, and Belmont. It's bounded by the Schuylkill to the east, Girard Avenue to the north, 48th Street to the west, and Sansom Street to the south.

Half of the 35,315 residents live in poverty, unemployment is high, and crime threatens everyone.

At the same time, though, the zone hosts energetic civic groups that say momentum is rising. The area abuts Center City and includes or is near 30th Street Station, the Philadelphia Zoo, Drexel University, and the University of Pennsylvania.

City officials and neighborhood leaders say it's a good place to invest, to bet on making a difference. The goals are to attract new businesses, increase employment, raise educational opportunities, and improve housing.

Many of the graceful Victorians that Skaler loved have been torn down or chopped into multiunit apartments.

His parents, Louis and Minnie, moved to the area in 1925. Skaler's father ran L. Skaler & Sons, a Kosher butcher shop, at 40th Street and Ogden. The family lived above the store.

Skaler was born in the house in 1936, went to Central High School, studied architecture at Penn. After graduation, he worked for Vincent Kling, whose work dominated the city in the 1960s.

In off hours, Skaler began photographing Victorian buildings, capturing their images and collecting others at postcard shows. He later donated nearly 4,000 cards to Penn, where they make up the Robert Morris Skaler West Philadelphia Postcard Collection.

"I had double vision," Skaler explained. "When I would look at something, I could see the way it was."

Postcards can be deceptively useful, containing information beyond photos. If they're dated, they can help determine the age of a building. Their style can lend clues - for instance, postcards with a white border were common from 1915 to 1930.

Today, Skaler's family home at 871 N. 40th St. is an empty lot. He wonders if something new might yet be built there and nearby.

The key, he said, would be to reduce crime, so people can be enticed to settle in the area. Small businesses will follow the people, and bigger companies will follow small businesses.

But cutting crime in the Promise Zone will be hard. The 2012 homicide rate was higher than the city average, the rate of aggravated assaults and robberies much higher, the rate of rapes double.

"If people feel safe, the neighborhood will turn around - it will do it on its own. Look at Northern Liberties," Skaler said. "If people start to move in and fix up the houses," it will change. "And they will if they feel safe."