The mystery of Little Ty, solved

Tyrone R. Parler came home from Vietnam, got a city job in Philadelphia, and hardly mentioned the war. He didn't keep in touch with friends from the Army, didn't bother to declare his veteran's status when he got a new identification card.

Tyrone R. Parler came home from Vietnam, got a city job in Philadelphia, and hardly mentioned the war.

He didn't keep in touch with friends from the Army, didn't bother to declare his veteran's status when he got a new identification card.

He died young, only 56 - never knowing that a contingent of historians, news reporters, and fellow soldiers would labor to unravel his connection to an enduring mystery of the Vietnam War.

"I loved him. I loved him," said a cousin, Bruce Giddings Jr., 57, of South Philadelphia. "One of the best people you'd ever want to meet."

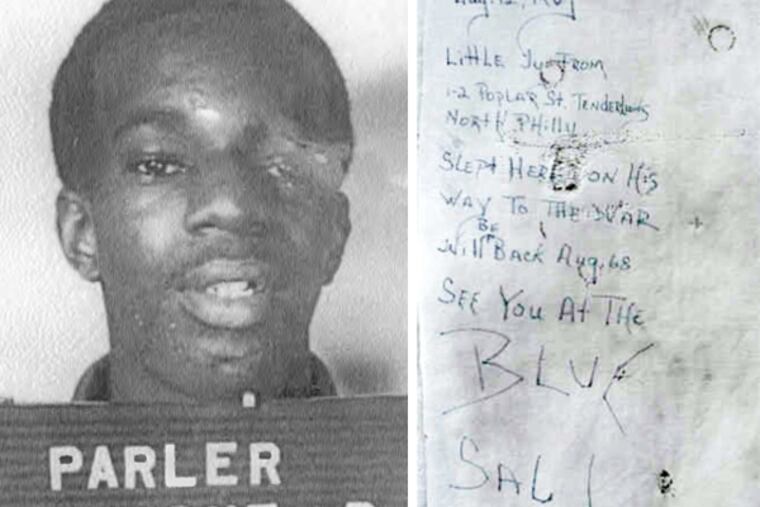

Only this month, long-sought connections between military records, ship rosters, and property deeds suggested that Army Pvt. Parler could be the elusive "Little Ty," whose scrawled 1967 troop ship message now belongs to the Smithsonian Institution.

Researchers hoped to find him - until last week, when, in seeking to locate him, The Inquirer instead confirmed his death.

"We're really sad that he has passed, and that we weren't able to show him the canvas," said Virginia military historian Art Beltrone, who in the late 1990s discovered hundreds of graffitied, Vietnam-era canvas bunks aboard an old troop ship.

On one rack was the message:

"Little Ty from 1-2 Poplar St. TenderLions, North Philly, slept here on his way to the war," he wrote, marking the date as Aug. 12, 1967. "Will be back Aug. 1968. See you at the Blue Sal!"

Little Ty, Beltrone said, possessed a unique optimism, a certainty that he would make it home alive.

A decade of periodic searches, including some by a Philadelphia detective, failed to unearth his identity. This month Beltrone discovered documents in his Vietnam archive that named the soldiers aboard ship when Little Ty wrote his note.

Among the 2,568 men on that voyage, only one was named Tyrone - Parler, of the 610th Engineer Company. He entered the service from Philadelphia and returned there after the war, living in a house on North 12th Street in East Oak Lane.

It turned out the Aug. 12 date on the canvas had special significance: It was Parler's birthday.

Parler's brother, Steve Williams of Richmond, Va., said he could not recall his sibling using the nickname "Little Ty." Perhaps it was a nom de guerre created for Vietnam, Williams said. At home, the family called him "Geech."

Williams said his brother definitely belonged to the TenderLions, a well-known North Philadelphia street gang in the 1960s. At the time, the family lived amid the area's huge public housing projects, and gangs ruled.

"Tyrone was part of the TenderLions," Williams said. "It was one gang you didn't cross."

Williams said he was puzzled by the reference to the Blue Sal - it was the legendary Blue Horizon, on Broad Street, where his brother and others hung out.

John Buchanan, a retired detective from the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office, recognized that Little Ty's use of "1-2 Poplar" was gang lingo for 12th and Poplar. Buchanan's search of the area turned up nothing on Little Ty.

But by then, the soldier who may have used that moniker was long gone.

Sadly, Williams said, his brother had a drinking problem. He died of alcohol abuse in 2001, two years after retiring from nearly three decades with the city Parks and Recreation Department.

"The doctor told him he had to stop," Williams said, "and he just kept on."

Parler's funeral was May 29, 2001, at the Terry Funeral Home in West Philadelphia. Mourners heard hymns, readings from the Old and New Testaments, and stanzas by poet Tianna Graham.

In tears we saw you sinking, and watched you fade away, the poem began.

Parler was cremated at West Laurel Hill Cemetery. Survivors included his mother and a son. He never married.

He was born Aug. 12, 1944, at Jefferson Hospital, according to his funeral brochure. He attended James Rhodes Elementary School through first grade, then moved to live with his grandmother in Denmark, S.C.

He studied at the Voorhees School and Junior College, and spent summers in Philadelphia with his mother, stepfather, brothers, and sisters. After leaving school, Parler came to Philadelphia. In April 1966, he was in the Army.

At that time, the era of big troop ships was ending. When the Pentagon needed to deploy large numbers of men, though, it resorted to traditional ships such as the Gen. Nelson M. Walker, which could carry up to 5,000.

The journeys were long and stressful. A man lying on his back had 18 inches from his nose to the bunk above, and three weeks to think about what lay ahead.

Beltrone found the canvases while working as a movie consultant, later conserving the jottings and drawings as the Vietnam Graffiti Project. The project spawned a book, website, and traveling exhibition, "Marking Time: The Voyage to Vietnam," now at the Independence Seaport Museum.

That exhibit includes a photo of Little Ty's canvas.

Parler was aboard the Walker when it departed Oakland, Calif., on Aug. 10, 1967. Two days later, he turned 23. In Vietnam, his job was supply specialist, responsible for maintaining and storing equipment. His unit supported road-building work but sometimes engaged in fierce firefights with the enemy.

In many ways, Parler was an Everyman of Vietnam, called to service and sent overseas, returned home to try to put the war in the past.

"We never spoke about our military service - most vets from the time didn't," said Roland Chandler Jr., who worked with Parler at the Recreation Department. "He was very low-key, very soft-spoken, easygoing."

Parler was hired as a Recreation Department laborer on Nov. 8, 1971, records show. Six years later he was promoted to recreation leader, put in charge of organizing everything from basketball games to drama productions.

"A good person to work with," said Talmadge Rhodes, a retired department supervisor. He said he could not recall Parler's ever mentioning that he had served in Vietnam.

But Williams, the brother, said Parler talked to him about the war, particularly the constant, unnerving fear he felt in Vietnam.

"He would talk about how the Viet Cong did this, the Viet Cong did that, how sneaky they were," Williams said. "He was an engineer, but he was getting bombed on. He said: 'I was scared, but there was nothing I could do. All I could do was keep myself alive.' "

Parler took classes at Temple University after being discharged in 1972. His GI Bill benefits enabled his family to buy the big house on 12th Street.

Parler sold his share of the house to his mother, Helen Giddings, for $1 in 1997. Two years later he retired.

On May 16, 2001, Parler sat for an identification-card photo at the Lawndale driver's license center, neatly inscribing his signature beneath his picture, but not declaring his status as a veteran.

He died a week later.

"Tyrone lived his life the way he wanted," read his obituary, "and never regretted anything that he had ever done in his life."

215-854-4906 @JeffGammage