In new 'Serial' podcast, Bowe Bergdahl says he likened himself to Jason Bourne

After slipping away alone from his tiny base in Afghanistan under cover of darkness in 2009, Army Pfc. Bowe Bergdahl had a sinking thought: His plan to draw attention to himself by spawning a massive manhunt was going to lead to a "hurricane of wrath" from his commanders.

After slipping away alone from his tiny base in Afghanistan under cover of darkness in 2009, Army Pfc. Bowe Bergdahl had a sinking thought: His plan to draw attention to himself by spawning a massive manhunt was going to lead to a "hurricane of wrath" from his commanders.

Bergdahl decided then to deviate from his plan to head straight from his platoon's base, Observation Post Mest, to the larger headquarters 20 miles away, Forward Operating Base Sharana, he said in an interview published Thursday by the podcast Serial. It marked his first interview since he was released in May 2014 after being held in captivity for five years by a group affiliated with the Taliban.

Bergdahl, comparing himself to a fictional action hero, said he decided to collect intelligence and look for the Taliban before turning himself in.

"Doing what I did is me saying that I am like, I dunno, Jason Bourne. . . . I had this fantastic idea that I was going to prove to the world that I was the real thing," Bergdahl said. "You know, that I could be what it is that all those guys out there that go to the movies and watch those movies, they all want to be that, but I wanted to prove that I was that."

But he got lost in some hills and was taken prisoner by enemy fighters on motorcycles who found him in open desert, he said.

"I don't know what it was, but there I was in the open desert, and I'm not about to outrun a bunch of motorcycles, so I couldn't do anything against, you know, six or seven guys with AK-47s," Bergdahl said. "And they pulled up and just. . . . That was it."

Bergdahl's comments aired in the first episode of a new season of Serial, the popular weekly podcast spun off from the public- radio show This American Life. The show's host and creator, Sarah Koenig, said in the episode that the new season will draw heavily from 25 hours of recorded phone calls between Bergdahl and Mark Boal, a filmmaker who began interviewing the soldier after he was released.

The podcast's focus on the case promises to draw even more attention to Bergdahl, who faces military charges of desertion and misbehavior before the enemy. It also will offer even more fodder in a case that already was heavily politicized, with many Republicans angry that the Obama administration opted to recover the soldier in a swap in which five Taliban officials were released last year from the military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. They remain under supervised release in Qatar.

Bergdahl's legal status remains in question. Evidence in his case was reviewed by the Army in a two-day September hearing, but the service has been tight-lipped about its plans for him. He faces up to life in prison, although the officer who oversaw the hearing has recommended against both the most serious kind of court-martial and prison time, according to Bergdahl's attorney, Eugene Fidell.

Fidell declined to comment on the production of the Serial podcast or to say how much knowledge he had of its development, but Koenig said in the podcast that Bergdahl gave her team permission to use the recorded phone calls. Fidell released a statement praising the first episode and repeating his legal team's call for the Army to be transparent and release documents associated with the case.

"We have asked from the beginning that everyone withhold judgment on Sgt. Bergdahl's case until they know the facts," the statement said. "The Serial podcast, like the preliminary hearing conducted in September, is a step in the right direction. We hope the Army will now do its part to advance public understanding by releasing Lt. Gen. Kenneth S. Dahl's report, including the transcript of his interview of Sgt. Bergdahl."

The statement continued: "Americans of good will should be afforded an opportunity, especially at this time of year, to judge the matter calmly and in its proper light."

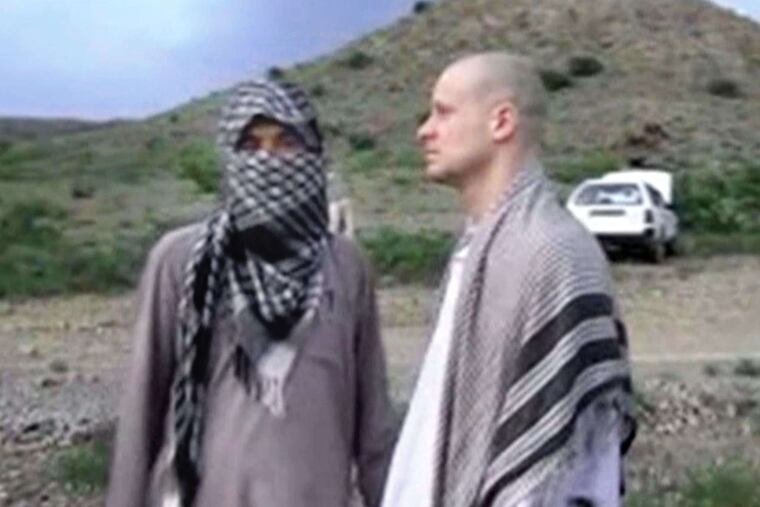

The 44-minute first episode opens with Koenig describing a Taliban propaganda video of militants handing over Bergdahl in Afghanistan to U.S. forces. But it is Boal's conversations with Bergdahl and the soldier's description of his capture and captivity that dominate it.

Bergdahl, now 29 and a sergeant, says in the podcast that he ran away from his base to prompt a "DUSTWUN," an acronym short for "duty status-whereabouts unknown." That matches testimony from Dahl, who said during the hearing in September that Bergdahl had told him in an interview that he wanted to speak to a senior commander to air grievances about his unit.

"What I was seeing from my first unit all the way up into Afghanistan, all's I was seeing was basically leadership failure, to the point that the lives of the guys standing next to me were literally from what I could see in danger of something seriously going wrong and somebody being killed," Bergdahl said in the podcast.

The general said in testimony in September that Bergdahl had an inflated sense of his ability as a soldier and drew conclusions that puzzled his colleagues. Dahl said that Bergdahl's childhood living at "the edge of the grid" in Idaho hurt his ability to relate to other people and prompted him to be a harsh judge of character and "unrealistically idealistic."

Military officials who interviewed Bergdahl at length said that he was tortured and kept in solitary while held by the Haqqani network, a group affiliated with the Taliban. Bergdahl alluded to that in the podcast Thursday.

"It's like, how do I explain to a person that just standing in an empty, dark room hurts. It's like, well, someone asks you, 'Well, why does it hurt? Does your body hurt?' Yes, your body hurts, but it's more than that. It's like this mental, like. . . . You're almost confused. You know, there was times when I would wake up and it's just so dark and it's so dark. Like, I would wake up not even remembering what I was."

Bergdahl continued: "You know how you get that feeling where that word is on the tip of your tongue? That happened to me, only it was like, 'What am I?' Like, I couldn't see my hands. I couldn't do anything. The only thing I could do was like, touch my face, and even that wasn't, like, registering right, you know? To the point where you just want to scream and you can't like, I can't scream. I can't risk that. So it's like you're standing there screaming in your mind in this room."

Bergdahl added that "everything is beyond that door. And, I mean, I hate doors now."

The soldier said that by slipping away from his platoon's base and reappearing at the larger base, he hoped to not only draw attention to problems he saw in his unit, but prove his own worth as a soldier. It would have been taking out two birds with one stone, he said.