Newspaper unearths 19th-century discrepancy about alleged lynching

PITTSBURGH - For more than a century, the death of David Pierce has been a stain on Western Pennsylvania as the only victim of a lynching in the region.

PITTSBURGH - For more than a century, the death of David Pierce has been a stain on Western Pennsylvania as the only victim of a lynching in the region.

The African American man was said to have shot and killed Sanford White, a white superintendent of a coke works near Dunbar, Fayette County, on the morning of Dec. 19, 1899, after Mr. White intervened during a fight between Mr. Pierce and another white coke executive, Richard Cunningham.

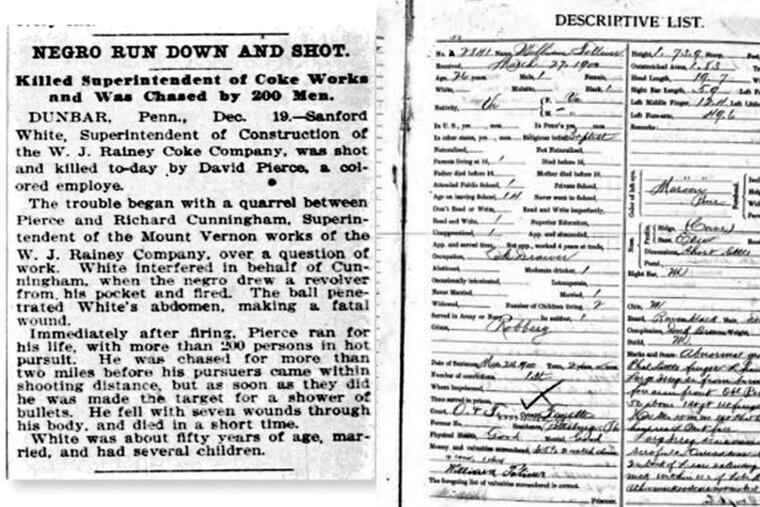

Pierce was described as a "Negro" and a "dangerous character" in the initial news report that went out over the telegraph coast to coast. It appeared in at least several dozen papers across the country including the Los Angeles Daily Times and the New York Times, which ran it under the headline: "NEGRO RUN DOWN AND SHOT."

That first story claimed that Pierce fled the scene, ran to the nearby mountains, was pursued by "an angry mob" of more than 200 people, and then shot in "a shower of bullets."

It seemed a textbook example of the Tuskegee Institute's definition of a lynching in which three or more people take the law into their own hands and kill someone in some way (not just by hanging) under the pretext that it served "justice, race, or tradition."

Pierce's death has been recorded as a lynching in nearly all of the most authoritative lists compiled over the years, starting in 1899, when the Chicago Tribune included it in the paper's annual lynching list.

But this blight on the history of Western Pennsylvania - long a center of the abolitionist movement and a major site of the Underground Railroad - has a problem: The lynching did not happen.

White was shot by a black man, but it was not David Pierce, who is referred to in a small number of news articles as Caleb Pierce.

The shooter's name was George Templeton. He was shot and seriously wounded, but he did not die at that time.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette uncovered this historic discrepancy after several recent studies were published trying to create authoritative lists of all of those who were lynched over the years.

Noticing the case of David Pierce on some of those and older lists, the idea was to tell the story of who he was and what happened leading to his unjust death.

But, it turns out, what really happened after White's murder is less a tale of a "lawless mob" exacting vengeance, as one headline put it, than of legal restraint and measured justice.

Templeton's story

There were various descriptions of what led George Templeton to shoot Sanford White early on the morning of Dec. 19, 1899.

But most of them agree that sometime early that morning, an employee of the R.J. Rainey Coke Co. - described merely as "a Hungarian" - told Richard Cunningham, the company superintendent, that he had been robbed the night before of $6 and a watch.

The description the victim gave seemed similar to Templeton, who was about 22, stood just 5 feet, 33/4 inches tall, and weighed 145 pounds. Single, with no children, he was originally from Mobile, Ala., and a Baptist by faith, according to state prison records.

He either worked at another coke works, or had not worked and "had been hanging around the coke works for a year or more, doing nothing, and lived off the men at the works by gambling," according to a Pittsburg Gazette story from March 15, 1900.

After Cunningham confronted Templeton about the robbery, Templeton got upset and, according to Cunningham, pulled a gun on him.

At that point, White came on the scene.

White was a well-known longtime rough-and-tumble coke superintendent, having worked in the Connellsville coke region for decades. He was single, had no children, and lived with his mother in Connellsville.

When "the large and powerful" White saw Templeton with a gun, he struck him in the face. Then, while "trying to wrest the revolver from Templeton's hands" as he stood over Templeton, who was on the ground, White was shot, according to Cunningham.

He said White managed to fire off several shots at Templeton after being shot, missing each time. But Cunningham said he then took Mr. White's gun and fired the shot that hit Templeton's neck, seriously injuring him as he fled.

At the two-day murder trial that followed in March 1900, Templeton took the stand and said he shot White in self-defense, according to the Gazette's Dec. 16, 1900, story.

Templeton said Cunningham came to his shanty early the morning of the shooting, "burst the door in" and accused him of the robbery. Angered, Templeton said he followed Cunningham to the coke works, where Cunningham got a hatchet. White then struck Cunningham.

"A struggle ensued and Templeton was shot [by White] as he was getting up," the Gazette said. Templeton said he then fled and fired over his shoulder - apparently hitting White then, by his account - beginning a chase into the countryside.

"I ran and saw about 17 or 18 people after me with shotguns and revolvers," the story quoted Templeton as saying from the stand. "One man who had a revolver as long as my arm came up and said, 'Halt,' but I kept on. I ran into the woods and was coming out of the blackberry bushes when the same man came up and said, 'Halt, throw up your hands.' "

The man who told Templeton to halt was Lemuel Kemel, who testified that when he confronted him, Templeton initially fired a shot, before throwing the gun away.

Because of his serious wound, Templeton was carried back by stretcher or cart to Mount Braddock, where he was put on a train to be taken to Cottage Hospital - now known as Highlands Hospital - in Connellsville, where he was treated.

The next day, Fayette County Sheriff George A. McCormick sent Detective Alexander McBeth to guard Templeton as he was put back on a train to take him to the Uniontown jail, where he stayed until the trial.

At the end of the trial, Templeton's defense attorneys argued that since White struck Templeton first before he shot White, "then he is not guilty of murder in the first degree," something the prosecution strongly objected to, the Pittsburg Post reported.

Though Templeton was black and apparently poor, he managed to get two good defense attorneys - W.N. Carr and T.H. Hudson.

On March 16, 1900, the all-male jury took nearly seven hours of deliberation before finding find Templeton guilty of robbery and just second-degree murder.

Eight days later, Judge R.E. Umbel sentenced Templeton to 15 years on the second-degree murder charge and two years on the robbery charge.

He was sent to the state prison in Pittsburgh two days later, on March 27, 1900, and served eight years and five months - with good behavior - before he was released on Aug. 24, 1909, according to state archive records.

What happened to Templeton after he left prison is not known. And there is no information about who David or Caleb Pierce was, if he was, in fact, a real person.

Lessons in the mistake

Though the mistaken story of the lynching of David Pierce appeared, lynching historians say that what the Post-Gazette found further illustrates the need for there to be an authoritative state-by-state accounting of each and every case.

"The lists that we have - from Tuskegee, the NAACP, the Chicago Tribune - they were doing the best with what they had at the time," said Amy Wood, a history professor at Illinois State University and author of Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940.

Because those original lists of thousands of lynchings often relied on people sending in paper articles cut from local newspapers, there are "definitely errors in those lists," she said. "And there is probably a lot undercounting" of cases that occurred but were not recorded on the lists.

The mistaken case of Pierce's lynching apparently occurred because the initial news report, appearing in print as soon as the afternoon papers on the day White died, relied on second- or thirdhand accounts of what happened. That became the story of record, despite later stories in the Pittsburgh papers that got most of the facts correct.

Jennifer Taylor Milligan, staff attorney for the Equal Justice Institute in Atlanta, which published an updated lynching list for southern states last year, said the Post-Gazette's discovery illustrates what her organization found: Using local news sources from so long ago is the most accurate way to confirm or recover information.

"We've made an attempt, as much as possible, to prioritize stories that are from local sources and have more information than others," she said.

Historians expect there to be other errors found among long-recorded lynching cases. But it is more likely, they say, that a thorough examination would find many more cases that were never reported on those old lists, something multiple recent studies have found, including EJI's.

"We know there are many" lynchings that did not get recorded on some of those early lists, said Stewart Tolnay, a history professor at the University of Washington, and an expert on lynchings. "But what is the proportion (of undercounting) to errors? We don't know yet."

Tolnay said most recent updates to lynching lists have been regional, including one he and his colleague, Woody Beck of the University of Georgia, did on southern states. But researchers are now discussing pooling their resources to come up with a complete, national database.

One of those researchers who might be involved is Michael Pfeifer, a history professor and expert on non-southern state lynchings at the Graduate Center at the City University of New York, who sees good reason to create such a list.

"The collective murder of these individuals without due process of law can tell us a great deal regarding the social, cultural and legal arrangements of the societies in which these acts occurred," he said in an email response to questions. "This is why we must try to document these acts as best we can including correcting erroneously reported incidents and uncovering cases that have not been previously documented in the historical record."