Dilapidation on his docket

The brick rowhouse on Erie Avenue has yellowed four-year-old newspapers on the windows instead of curtains. Its steps are crumbling, its fence is rusted, and its yard is choked with weeds and garbage.

The brick rowhouse on Erie Avenue has yellowed four-year-old newspapers on the windows instead of curtains. Its steps are crumbling, its fence is rusted, and its yard is choked with weeds and garbage.

"Disgusting," said Ronald Allen, who lives around the corner. "It's all trash back there, piling up, looking awful."

There's a sign on the door: "For Rent, 215-683-7124." Dial the number and the phone rings in the chambers of Common Pleas Court Judge Willis W. Berry Jr., who is running for a seat on the state Supreme Court.

An Inquirer investigation shows that the judge owns 11 properties in North Philadelphia, some of them even more decrepit than the one on Erie Avenue.

Berry manages this portfolio from his judge's office in possible violation of state ethics rules, the investigation shows.

Some of Berry's apartments, where tenants have complained about mice and roaches, have a history of code violations. Others are worse - dilapidated, dangerous eyesores that residents say are a blight on their neighborhoods. Among them:

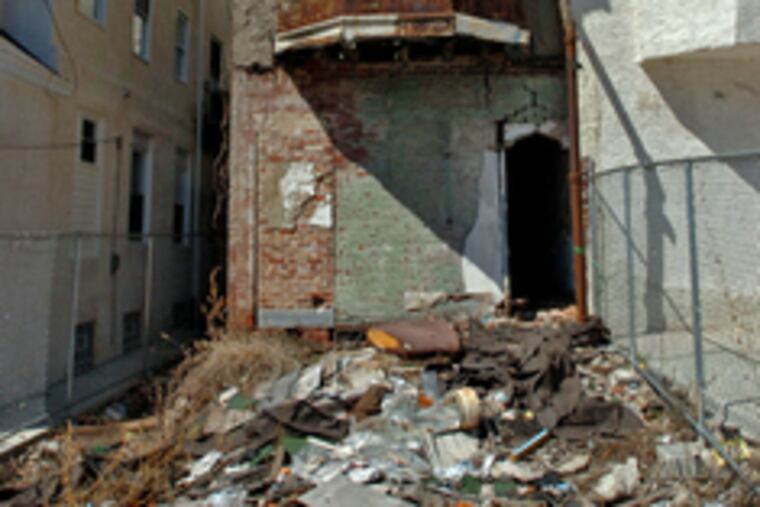

A four-story apartment building at 1435 Poplar St., which Berry bought from a city agency, promising to fix it up. Fourteen years later, it sits empty and crumbling, with pigeons roosting in its rafters and a pile of trash where its front steps used to be. After questions from The Inquirer, the city recently declared the building "imminently dangerous."

At Erie and Sydenham, mice dart about inside an empty rowhouse. Boards and plastic tarps cover some of its windows. The yard - used as a stash by drug dealers, neighbors say - is littered with debris, shards of glass, and a soiled diaper thrown against a fence.

On North 15th Street, a hollowed-out building owned by Berry sticks out in a row of freshly renovated homes. Its splintered front door is held in place with a chain threaded through a hole where the doorknob should be.

Neighbors weary of living beside the squalor of Berry's buildings say he has ignored their complaints.

"It's terrible," said Vance Renwick, who runs a hotel down the street from the vacant property on Poplar. "I just can't believe, with him being a judge, that he can't fix this property up."

Berry, 64, who has served on the bench since 1995, went on a tour of some of his properties with an Inquirer reporter and promised to get rid of the trash and make repairs.

The problem, he said, is he does most of the work himself. In recent months, he said, he has focused on his Supreme Court campaign.

"I messed up because I'm not working on the properties now," the judge said in an interview last week. "I'm just concentrating on this election."

He dismissed tenants' complaints as exaggerated: "These are nice apartments. . . . These people are living in apartments that's better than my house, really."

Berry, who is paid $152,000 a year as a judge, also said financing the repairs had been a problem: "I can't seem to borrow no money," he said.

'Better to know a judge'

Berry began his legal career in the law office of Cecil B. Moore, the civil-rights leader and city councilman. After Moore's death, Berry opened his own firm.

He made his first bid for a judgeship in 1985, running with the endorsement of a committee with a controversial slogan: "It's good to know the law. . . . It's better to know a judge." He lost. He ran again in 1995, this time with the backing of the Democratic Party, and won.

Berry said he was seeking higher office because trying cases in criminal court was not especially challenging.

"It's a nothing job," he said. "Anybody can do it if you can keep an open mind and be fair. Don't really require any special training."

In his campaign for Supreme Court, Berry describes himself as a long shot, even though he drew top ballot position in the May 15 primary. His campaign-finance report shows no contributions.

Throughout his career, Berry has dabbled in real estate, rehabbing buildings himself. "I cut off my fingers in here," he said, holding up his hand. "I fell through roofs. I fell through floors."

He did elaborate work on the outside of his former law office on Girard Avenue and has renovated two apartments inside, including one rented to a Temple University professor. He's working on others, and the place is chock-full of supplies, including tools, boxes of bricks, bags of concrete, and two table saws.

"I do everything myself," Berry said as he led a reporter on a tour of the building. "I learned to fix just about everything just by reading up on it and by doing it."

Trouble is, he said, "I always start something, then get waylaid by something else."

A broken pledge

When he bought the four-story building on Poplar Street from the city Redevelopment Authority, Berry paid $7,000 and promised he'd restore it within a year.

The address, 1435, is spray-painted over the boarded-up front door, just above a patch of broken bricks filled with trash: an empty bottle of E&J Brandy, a Styrofoam takeout container, spent 40-ounce bottles of Silver Thunder Malt Liquor, a half-empty bottle of diet Snapple.

On April 17, after The Inquirer asked about the property, the city Department of Licenses and Inspections sent Berry a notice declaring the building "imminently dangerous." L&I said a recent inspection had found that the roof, walls and floor had partially collapsed. It ordered Berry to repair or demolish the building.

Neighbors said they had complained about the property for years - to Berry and the city - to no avail.

A few years ago, neighbor Renwick said, squatters moved in. "I was scared the place was going to go up [in flames] with the drug addicts in there like that."

So he said he had picked up a hammer and nails and boarded up the place himself. He repeatedly called the judge's office to complain, and eventually a construction crew sealed off access to the first floor.

City housing officials, in response to questions from The Inquirer, said they had no idea the property was in such sorry shape years after Berry pledged to fix it up.

On April 17, the city's Office of Housing and Community Development sent Berry a letter saying the city had sold him the building in part because he had promised to turn it into affordable housing.

"The property was not developed as originally proposed," the letter said, adding that the city had a right to take it back if Berry did not keep his pledge.

Berry said he would finish the renovations. "That's a doable building," he said. "We did a lot of work on it already."

That's not the only vacant and derelict property in Berry's portfolio.

A few blocks away, at Erie and Sydenham, sits a three-story rowhouse that he bought at a sheriff's sale for $5,100 in 1993.

The yard has been used as a virtual dump. On a recent day, it was filled with scrap wood, chunks of concrete and broken glass.

"No trespassing. Keep out," reads a sign on the front door.

Neighbors said the property had become a haven for squatters and a magnet for drug dealers, who hide their stash in its cluttered backyard.

"He's been neglecting this for years," said Ronald Allen, who lives in a neat, tan-brick house behind Berry's property. "We can't even open up our windows in the summertime."

Allen said he wouldn't let his four sons play on his front porch, which looks out on the filthy yard.

Florence Thompson, who runs a cleaning service out of the rowhouse next to Berry's, said she constantly battled rodents.

"He don't clean nothing, and the mice - the mice are coming to my side," she said, shaking her head. "He's costing me money because I have to pay [an exterminator] once a month."

Shown photographs of the property, Berry said he had no idea it was in such terrible condition.

"I didn't know it was that bad," he said. "We'll get somebody over there to clean it up."

William L. Dent, 80, an eye doctor with an office across the street, has been a fixture in the neighborhood for 48 years. He said he thought Berry had made a poor investment.

"I hope he knows more about law than he does about real estate," he said.

Some of Berry's investments have paid off. A building he bought at a sheriff's sale for $4,700 in 1993 sold for $57,500 in 2005, when the Board of City Trusts bought it to rehab as affordable housing.

John J. Egan Jr., president of the board, said it had wanted to acquire Berry's building because it owned properties on either side. Initially, he said, the judge asked for $95,000, a sum the board had considered "exorbitant" because the property had not been renovated.

"It was a disaster," Egan said. After a year of negotiations, Berry accepted the lower price.

"I sold it for less than what it was worth," Berry said.

A block marred

On the 1300 block of North 15th Street, there's a row of four newly renovated homes, with fresh white paint and shiny brass doorknobs.

This portrait of urban renewal is marred by one rowhouse that's visibly falling apart. Berry owns that one.

Tenants in the rehabbed units next door pay $1,500 a month for a view of Berry's trash-cluttered yard from their patios.

"It was a little disturbing at first," said Karry-Ann Nelson, 22, a senior at Temple who moved into the building next door in August, "but after a while you get over it."

Shown a photo of the yard, Berry said he hadn't known it was in such bad shape, and promised to clean it. "We had a fence there," he said. "They took it down, and they dumped."

Berry was unapologetic that his vacant building was a blight on the block's renewal. He said some damage had been caused by the renovations.

"He knocked down my wall," the judge said. "Now he wants me to sell it. He can kiss my behind."

The owners of Kaya Investments, which purchased and rehabbed the houses adjacent to Berry's property, did not return phone calls seeking comment.

Berry said he was in no hurry to sell the property, or fix it up.

"When the price is right, we sell," he said. "That's what you do in real estate."

Unhappy tenants

Berry also owns rental properties, some of which have drawn complaints from tenants and violation notices from L&I.

Others, such as a building he owns on the 2400 block of North 15th Street, appear to be in much better shape. That building, where his daughter lives, has a new front door and a planter filled with pansies beside its front steps.

"He's a good landlord, but of course I would say that," she told a reporter. "I'm his daughter."

The judge said he worked hard to maintain all his properties. He was dismissive of former tenants' complaints.

"Tenants always complain," he said. "Some of them will say any f-ing thing, excuse me. I work on these properties after court every day."

Berry invited a reporter to see two vacant apartments in the three-story building he owns at 727 N. 17th St., fishing the keys out of a tangle of key chains he keeps in an empty milk carton.

The apartments were small and spare, with aging appliances, drab cabinets and sagging floors. In one, a dead mouse lay on the kitchen floor beside a mousetrap.

"Ah, that is a mouse," the judge said and turned to a reporter. "Just be cool."

Berry has about 20 apartments in all, scattered among five buildings, that rent for $500 or $600 a month, he said. He said he took care of them himself with occasional help from Henry Reddy, his court-paid judicial aide.

The property on 17th Street was inspected in February after a tenant complained that there was no heat, an L&I spokeswoman said. An inspector found eight code violations, including problems with the heating system and inoperable fire alarms.

"The conditions found at the subject premises are dangerous to human life and/or public welfare," the inspector wrote. "These conditions constitute an emergency and must be corrected immediately."

Berry acknowledged past problems with L&I, but said he had corrected all violations.

However, an L&I spokeswoman said there were still violations at the 17th Street property. Inspectors were "working with him," she said.

Former tenants said the building was ridden with roaches and rodents.

"The mice was intense," said Pamela Gibson, 49, who paid $400 a month for a first-floor efficiency. She was evicted four years ago after she lost her job as a meat packer and could not keep up with the rent.

"One time, I was washing dishes and I saw one, and the next thing there was two mice in my dishwater," she said.

In the winter, Gibson said, the apartment was cold and drafty. "The wind just comes right in," she said. "I had to put plastic up to the window."

Gibson said she had stayed because she couldn't afford to live elsewhere. "I had nowhere else to go," she said.

Orlando Caquias, who rented a $500-a-month apartment from November 2005 until he was evicted last spring, said he'd had the same problems.

"It was infested with rats and roaches," he said. "Sometimes I was embarrassed to bring people over because I'd have to leave all the lights on so the roaches wouldn't come out."

Berry said the pests were his tenants' fault. "Some of them don't put out the trash, and we have to get an exterminator," he said.

One tenant said Berry had him evicted in retaliation after he reported mold, water leaks and electrical problems in an apartment at 1425 W. Venango St., near Temple.

"I took it because he was a judge," Robert Richardson-Hill said. "I thought Mr. Berry was a pillar of the community."

In a 2005 complaint to the city's Fair Housing Commission, Richardson-Hill said he had received an eviction notice weeks after telling Berry of water leaking out of an electrical socket in the bathroom and "oozing yellow stuff" on the walls.

The commission ordered Berry to return Richardson-Hill's security deposit and forgive his $400 monthly rent for the previous three months. Richardson-Hill was given three days to move out.

Berry's three-story brick rowhouse is one of the best on a block of derelict and boarded-up buildings, including one recently gutted by fire.

"I been here since '86, and it doesn't look like much has changed," he said.

"We've had plenty of complaints at Venango. Nothing lately," Berry said as he led a reporter to the building. "We had to put on a whole new roof." He was unable to enter the apartments because he did not have the right keys.

Berry said he was eager to get off the Supreme Court campaign trail and back to working on his properties. He said tending to them was a challenge.

"Look, we got a lot of properties, and all of them need some work. It's an everyday battle."