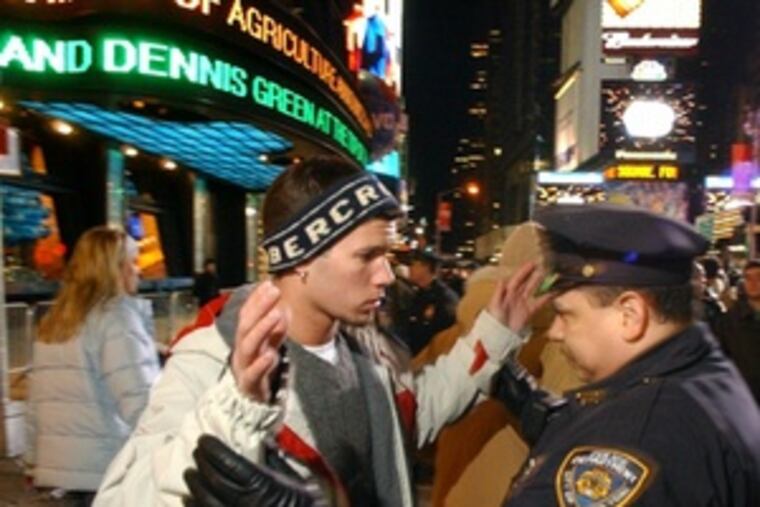

Stop-and-frisk controversy: What price for a safer city?

With three out of four intended voters telling pollsters that crime is the issue driving Tuesday's mayoral primary election, no proposal has drawn more heat - from opposing candidates and people on the street - than Michael Nutter's support for the police tactic he calls "stop, question and frisk."

With three out of four intended voters telling pollsters that crime is the issue driving Tuesday's mayoral primary election, no proposal has drawn more heat - from opposing candidates and people on the street - than Michael Nutter's support for the police tactic he calls "stop, question and frisk."

How does stop-and-frisk work? What is legally permissible? What is not? And why is it so controversial?

One expert says such policies may well help get guns off the street - but carry a potential risk of civil-rights violations.

"The empirical evidence from New York City is that stop-and-frisk as a policy for getting guns off the street helped. I think that's fair to say. The fact is that more surveillance in society tends to be effective," said University of Chicago law professor Bernard Harcourt.

"The only question is, where do you want to set the level of surveillance? It's a cost-benefit analysis," he said. Cities need to weigh the potential benefits against "liberty interests and the inevitable racial disparities and increased complaints of police misconduct" that have followed such programs, he said.

Nutter, for his part, is unswayed.

"We will protect people's civil rights, but no one has a right to carry an illegal weapon," he said in a recent debate. "People are desperately crying out for something to be done now. People have a right to be safe and not to be shot."

He did not respond to phone calls seeking comment for this story.

Despite some wishes to the contrary by frustrated people in dangerous neighborhoods, stop-and-frisk does not give police carte blanche to roust and pat down anyone and everyone.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in Ohio v. Terry, a 1968 decision, found that a frisk - in which police may pat down a person's outer clothing before they question him - is permissible.

But for the frisk to be constitutionally valid, police must have a "reasonable suspicion" that a crime has occurred or that criminal activity "is afoot." A mere hunch is not enough, the court said, adding that the officer must be able to clearly state why he thought the person might be about to commit a crime.

In Pennsylvania, the state Supreme Court has also been strict in setting controls over when police can stop and pat down suspects: "Any curtailment of a person's liberty by the police must be supported by a reasonable and articulable suspicion that the person seized is engaged in criminal activity."

In practice, police who are trying to find illegal weapons aggressively enforce minor laws such as curfew, loitering or drinking in public as pretexts for stop-and-frisk.

But on the street, the line between a permitted frisk and an illegal one can be blurry.

Is the man in a high-crime neighborhood wearing a long winter coat on a hot summer day hiding a shotgun? Or is he mentally ill and just inappropriately dressed?

Are the teens who appear to flee at the sight of an approaching squad car hiding criminal activity? Or are they innocents clearing off the street in anticipation of a guns-drawn clash between police and the actual neighborhood bad guys?

This intense style of enforcement is often referred to as the "broken windows" approach - the theory that cracking down on minor problems can reduce larger crimes and violence.

Critics say the approach can backfire.

"You don't want to create unnecessary contacts that are debilitating to the community," said Harcourt. "Police have to proceed with extreme caution."

Proponents say it's also been effective.

Using stop-and-frisk to crack down on illegal guns in one high-crime neighborhood in the early 1990s, an elite squad of Kansas City, Mo., officers increased gun seizures by 65 percent.

Gun crimes, including killings and aggravated assaults, went down by 49 percent, according to University of Pennsylvania criminologist Lawrence Sherman, who helped create the program. Nutter often cites Sherman's work to support his stop-and-frisk proposal.

Similar programs in Los Angeles, New York and Minneapolis also have succeeded in dialing down homicide rates.

But New York's success has not been without controversy, including the 1999 killing of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed man.

Also in 1999, a report by then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer analyzed data from 175,000 police stops and found stark racial disparities.

"Blacks were more than six times more likely to be stopped than whites, and Hispanics were more than four times more likely to be stopped than whites," wrote Pace Law School professor Bennett L. Gershman in a law-journal article that asked in its title, "How Far Can the Police Go?"

Amid continuing controversy about the stops, New York's Police Department - which denies that race plays a role - recently hired the RAND Corp. to do an independent review.

A poll released yesterday found Philadelphians generally support stop-and-frisk, though blacks are more ambivalent than are whites. The telephone survey of 802 people 18 and older, sponsored by the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia and conducted by Temple University's Institute for Public Affairs, found that two-thirds of whites favored the policy. Blacks favored it by a slim majority - 52 percent. The margin of error was 3.5 percent.

"Black Philadelphians are more ambivalent than white Philadelphians about stop-and-frisk because they are more skeptical about the city's police," a release issued with the survey declared.

"Blacks in Philadelphia are more likely than whites to feel unsafe, in their neighborhoods and in their homes," said institute director Michael G. Hagen, "but even when we compare only people who feel unsafe, blacks are much less satisfied than whites with police protection."

Harcourt, the law professor, said the toughest issues surface when "hot-spot" policing brings a flood of officers into a predominantly black neighborhood.

"How do you deal with the racial profiling that takes place? Is it racial profiling if you are in an African American community?"

While it can be argued that police are targeting crime zones - not minorities - perception matters, he said.

"In America in 2007, it's impossible to distinguish the sensitive issues of race from the troubling issues of crime," he said.

Former Atlanta Deputy Police Chief Lou Arcangeli said communities typically support stop-and-frisk, at least at the outset. But support can wane, especially if it seems to be used disproportionately against people of a particular race.

"African American parents have told me that they were uncomfortable with their sons being constantly stopped and frisked," said Arcangeli, now a professor of criminal justice at Georgia State University.

He said people in high-crime neighborhoods initially are glad when police make stops and even accept when their own kids are frisked.

"But by the third or fourth time," he said parents told him, "it didn't feel good at all. It felt like harassment."