Phila.'s campaign limits are upheld

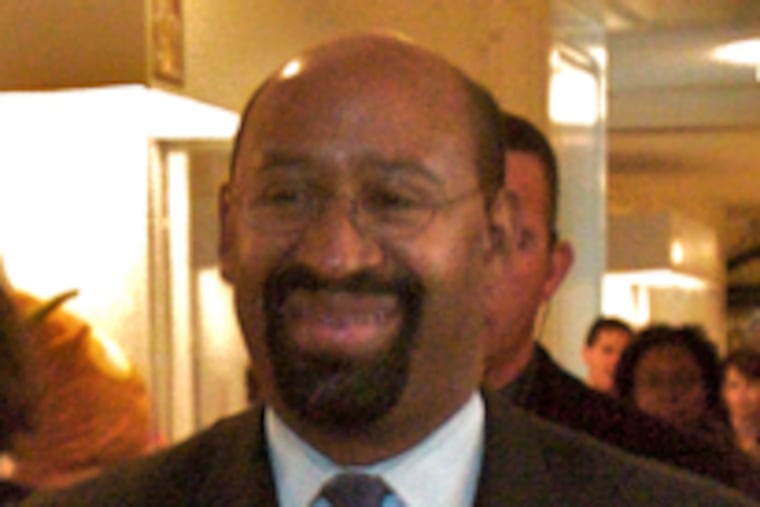

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has upheld Philadelphia's campaign-finance limits, a victory for reform-minded Mayor-elect Michael Nutter just days before his inauguration.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has upheld Philadelphia's campaign-finance limits, a victory for reform-minded Mayor-elect Michael Nutter just days before his inauguration.

In a 5-2 opinion, the court chose not to restrict the city's Home Rule powers, reasoning that the absence of contribution limits in state law opened the door for municipalities to enact their own.

"The state legislature, in fact, intended not to foreclose local regulation of campaign contributions for local elections," Justice Max Baer wrote in a 26-page opinion posted yesterday on the court's Web site.

Chief Justice Ralph Cappy, in dissent, wrote that the legislature's silence on campaign limits "speaks volumes" about its intent not to allow municipalities free rein in setting campaign caps. The majority's opinion threatens a "balkanization of the Election Code," Cappy wrote, quoting previous arguments.

Candidates' voluntary recognition of the contribution limits in this year's mayoral race helped Nutter, who relied on smaller contributions, to win the Democratic primary and coast to victory in the November election. He takes office a week from today.

"Elections should be about policy, about issues, about ideas, about getting more people involved at the ground level, not just a few people who can make large contributions," Nutter said yesterday. "The public can see for the first time in Philadelphia that grassroots campaigns mean something and that the financial and volunteer support that people give to campaigns has value."

It was an April 2006 lawsuit by then-City Councilman Nutter that started the dispute that ended up in the state's high court.

Nutter at that time sought an injunction in state court, seeking to force all mayoral candidates to abide by Council's 2003 law setting contribution limits at $2,500 per year for individuals and $10,000 a year for political committees.

A subsequent amendment, aimed at millionaire mayoral candidate Tom Knox, called for a doubling of those limits in any race in which a candidate contributes $250,000 or more of his or her own money. That effectively set the limits in the mayor's race at $5,000 for individuals and $20,000 for committees.

Potential mayoral candidates John Dougherty, the electricians union chief, and U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah (D., Pa.) fought back in court. Dougherty never ran; Fattah lost to Nutter in the May primary. Both appealed to the state Supreme Court.

Dougherty declined to comment yesterday. Fattah's lawyer, Philadelphia election-law specialist Gregory Harvey, said neither Fattah nor he opposed what Council was trying to do.

"Our disagreement with City Council was whether Council had the power, without explicit authorization from the legislature, to enact dollar limitations," Harvey said.

City Councilman W. Wilson Goode Jr., who introduced the original campaign spending limits that were approved in December 2003, called the ruling "very symbolic as we usher in a new administration."

Goode said the law, introduced before the pay-to-play scandal that rocked City Hall and the administration of Mayor Street in 2003, but passed as an antidote to "pay-to-play" afterward, intended to "empower the average voter and the one-person-one-vote system over all special interests, whether it be businesses, unions, or any other special interests that may exist."

David Kairys, a Temple University law professor, said the opinion was notable for acknowledging the importance of cleaning up the city's political process and giving the city the latitude to deal with that problem.

"The whole way it approaches the need for reform is, I think, a welcome change, and a good way for Mayor Nutter to start in his new office," Kairys said.

The law's influence is already being felt beyond this year's mayoral election, said Zack Stalberg, president of the Committee of Seventy, a government watchdog group.

"It's clearly changed the landscape already, in the sense that the big donors - the corporations or law firms or unions with big political action committees - are already finding themselves with less clout," Stalberg said.

Stalberg pointed to Council's recent clash with the building-trades unions over the expansion of the Convention Center. After threatening to open up the $700 million project to nonunion labor in a dispute over minority hiring, Council reached a deal in which the unions would have to submit plans for increasing their minority membership.

"Under previous landscapes, City Council wouldn't even have raised the idea of nonunion labor at the Convention Center," Stalberg said, noting that the city's building trades were accustomed to spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on local races. "You can buy a whole lot less influence with $20,000 than with $600,000."

That's not to suggest the work is done, Stalberg said.

He called on Nutter to make good on a campaign pledge to convene an independent panel to review local campaign laws and recommend any needed changes.

Meanwhile, echoing Cappy's concerns about Pennsylvania becoming a patchwork of varied election laws, Harvey said he expected other towns would get busy drafting their own limits on campaign giving.

"All Home Rule municipalities are invited by this decision to enact campaign-finance limitations if they desire," he said. "And I expect that some will."

But for any such change to take root, it has to not only be adopted but become "part of the political culture," said Randall Miller, a history professor at St. Joseph's University who follows city politics.

"Then it becomes not just emblematic," he said, "but actually functional."