Maplewood a living memorial to WWII veterans

Long ago, in the sepia days between world wars, the Chubbs and the McLaughlins were neighbors on West Court Street in Doylestown. Sixty-five years later, the three remain neighbors of sorts back in Doylestown. They, along with eight other local sons killed in World War II, are namesakes of a unique, postwar neighborhood.

Long ago, in the sepia days between world wars, the Chubbs and the McLaughlins were neighbors on West Court Street in Doylestown.

Harry Chubb was assistant postmaster of the Bucks County borough of 5,000, where he and his wife, Ethel, reared seven children in a three-story twin. In a converted carriage factory next door lived auto dealer George McLaughlin and his wife, Anna, parents of three.

By early 1944, with Hitler's forces still dominating Europe, three of those offspring were neighbors anew in England, stationed there with the U.S. Army Air Force.

Staff Sgt. George B. McLaughlin Jr. - friendly, flame-haired "Bud" to those back home - had gone from intellectual pacifist to ball-turret gunner on a B-17 bomber.

Second Lt. Mary E. Chubb, a lively, bespectacled nurse, was tending the sick and wounded with the Women's Air Corps.

Her kid brother, Second Lt. Donald W. Chubb, a slight, fun-loving B-17 copilot, had just arrived overseas.

All three would die within a seven-week span surrounding D-Day, the June 6 Allied invasion of Normandy.

McLaughlin, 26, perished April 28 on a bombing raid over France. Donald Chubb, 22, died May 8 over the English Channel, keeping his shot-up Flying Fortress airborne long enough for crewmates to bail out before the plane exploded. Mary Chubb, 31, was killed June 14 in a plane crash in England.

And yet, 65 years later, the three remain neighbors of sorts back in Doylestown.

They, along with eight other local sons killed in World War II, are namesakes of a unique, postwar neighborhood - an Ozzie-and-Harriet setting at once steeped in history and brimming with life.

Each of the 11 streets in the borough's Maplewood development is named for one of Doylestown's fallen. But that is not all that sets it apart.

Maplewood arose from an unheard-of plan, hatched by the local Veterans of Foreign Wars chapter, to take the peacetime demand for new housing into its own hands.

In 1946, members of VFW Post 175 formed a development corporation, emptied their $38,000 building fund, and bought a 104-acre farm on the outskirts of town. The corporation laid out streets, had the borough annex the land, and began selling lots to returning veterans.

The project was "believed to be the first and only one of its kind in the nation's history," The Inquirer reported in November 1946.

After a strapped and rocky start, an array of Cape Cods, ranchers, and split-levels slowly began to sprout on the farmland east of Swamp Road. Most early buyers were veterans, but sales soon expanded to the public.

When construction ended in the 1960s, roughly 200 houses lined the 11 streets.

Today, empty-nesters mingle with children on bikes on Maplewood's tidy streets, shaded by onetime saplings grown tall and leafy. A 35-acre park, donated by the VFW in 1959, buzzes at night with baseball games and the shouts of children on the playground.

"Every time I come back to Doylestown, I go there," said Dick McLaughlin, 83, Bud McLaughlin's younger brother. "I knew just about all of the people that the streets were named for.

"It's a unique memorial, and I wonder sometimes why it doesn't get more recognition," said McLaughlin, a retired high school teacher and counselor in Naperville, Ill. "It was dedicated to a large group of veterans, it became a beautiful community, and it gave the veterans who came back an opportunity to have affordable housing."

Homes originally purchased for $10,000 now fetch upward of $300,000, and many are passed down within families. Modest by today's McMansion standards, Maplewood is mostly white-collar, but without the heavy starch.

"It's a wonderful place with great kids and nifty families," said Flo Smerconish, a longtime Doylestown Realtor. "When you buy there, you tend to stay forever."

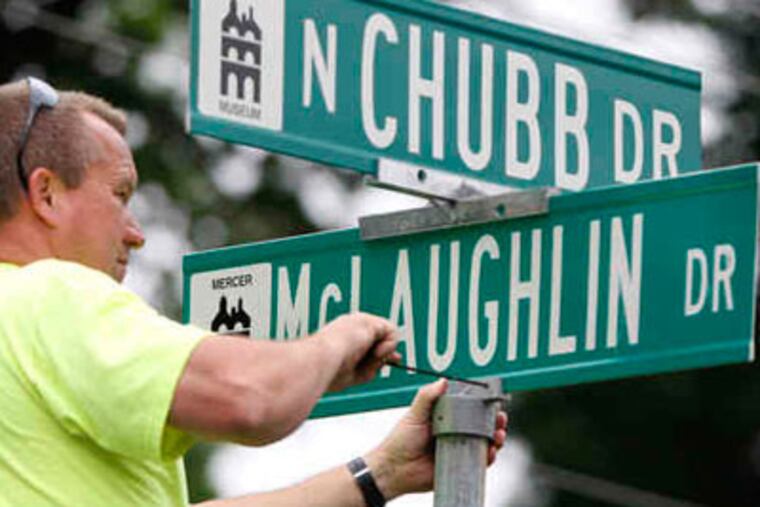

Among the original owners is Nick Chubb, 76, a nephew of Mary and Donald Chubb. Fittingly, his 1955 Cape Cod sits at North Chubb and McLaughlin Drives.

"I bought this lot because I liked it, not because I wanted to live on Chubb Drive," the Army veteran said.

"Now, Nick," said his wife, Marion, "I'm sure it was in the back of your mind."

"It was not," he shot back. "But at least I never get lost."

Both started laughing.

"That's the corny sense of humor," Marion said, "that has gotten the Chubbs through everything."

An unlikely warrior

Coming of age in 1930s Doylestown, Bud McLaughlin seemed an unlikely warrior.

He was a thoughtful, laid-back scholar who loved the theater, music, literature, and architecture. He had completed two years of premed studies at Johns Hopkins University, was leaning toward theology, and took a lot of ribbing in town for his antiwar views.

"At that time it was not very popular, but he was a pacifist," his brother recalled. "Then came Pearl Harbor. That happened on Sunday; he enlisted on Monday, and I think he left on Tuesday."

After training to be an aerial gunner, McLaughlin landed in England in October 1943.

His old neighbor, Mary Chubb, arrived a month later.

Her 1931 Doylestown High School yearbook hints of frailty - "Mary would like to become a nurse if her health permits" - but she had made it through the Chestnut Hill School of Nursing. She had worked as a private nurse before enlisting on the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor.

Small, bubbly, and caring, Mary sent letters from England that told of encountering McLaughlin there. On Christmas Day, she mailed her mother a loving poem she had composed for her, said Sara Crouthamel, 85, of Doylestown, her only surviving sibling.

Donald Chubb's ambition was "to fly around the world," his 1941 yearbook said.

"Don was one of my best friends, and his one goal in life was to be a pilot," Dick McLaughlin said. "Flying was his destiny."

He was also a mischievous sort, once rumored to have flown a plane under a bridge. "He loved to have fun," Nick Chubb recalled.

Donald Chubb turned up in England early in the spring of 1944, and met his sister at least three times.

By then a cross-channel invasion of France was imminent; the only questions were where and when. In advance of the landing, a massive Allied air campaign dropped nearly 200,000 tons of bombs on strategic targets in France and Germany between April 1 and June 5.

But the price was steep. More than 2,000 Allied aircraft were lost - two of them carrying Bud McLaughlin and Donald Chubb.

On April 28, McLaughlin's plane, the "Georgia Rebel II," left Ridgewell, England, to bomb a German-held airfield at Avord, France. Around noon, his B-17 had just released its bombs when it was hit by flak. Surrounding pilots reported seeing an engine explode and fall away as the plane veered off and crashed.

Only three in the 10-man crew survived. McLaughlin, found amid the wreckage, was buried nearby a few days later, alongside his six comrades.

His family did not learn of his death until August, though he had been reported missing on the front page of the May 20, 1944, Doylestown Daily Intelligencer.

By coincidence, on the same page, to the left of McLaughlin's photograph, appeared a large picture of Mary and Donald Chubb in uniform, smiling with two other Doylestown servicemen at an air base in England.

No one back home yet knew that Donald Chubb had been killed 12 days earlier.

Chubb's May 8 mission to Sottevast, on the Cherbourg peninsula of Normandy, had been only his fourth, said Bob Estler, 67, whose wife, Donna, is one of the Chubbs' nieces. The target that day was a huge concrete bunker the Nazis were building to house and unleash their new V-2 long-range rockets.

"His mission was to make sure they could never launch V-2s against England," said Estler, of Wheaton, Ill., who has researched the family's military history.

As the formation of Flying Fortresses approached the target that afternoon, heavy German flak met them. It hit the plane directly ahead of Chubb's, blowing off its tail and sending it spinning downward, a member of Chubb's crew later said.

Then two of the four engines on Chubb's B-17 were hit, knocking out its oxygen system. A shell exploded under the metal plate beneath Chubb's seat. Another burst took out the tail wheel.

"We were on the point of bailing out after the No. 4 engine caught fire," Staff Sgt. George Yeager Jr., the tail gunner, said in a post-mission report. But when the fire went out, "we decided to try to make it back to the coast."

Lt. Carl Kuba, the bombardier, jettisoned the bombs to lighten the weight. "No one had been wounded by the flak. . . . I called on the interphone and everyone answered," Kuba reported afterward.

Another flak round hit the left wing, almost tearing it off and setting fire to the fuel tank between the two left engines. The pilot, Second Lt. James W. Brown Jr., ordered the crew to bail out, while he and Chubb remained at the helm.

Kuba and Yeager were the last of eight men to parachute into the frigid water of the English Channel. Struggling to shed their chutes, the men watched as the plane descended. An explosion sounded.

"It went into a dive and then hit the water and sank," Yeager reported. The B-17 surfaced, then exploded again.

Only Kuba and Yeager survived, swimming for 90 minutes to ward off hypothermia before a British rescue plane picked them up. The other six who made it out of the plane drowned or died of exposure.

Yeager was killed two months later on a mission to Germany. Kuba died in 1970, the only crew member to see the war end.

For his heroism, Donald Chubb was awarded the Bronze Star, Estler said. His body was never recovered.

The first telegram reached the Chubb home on May 22, reporting Donald missing in action. A few hours later, a letter arrived from Mary Chubb, saying she was trying to get more information, the Daily Intelligencer reported.

The next telegram came from the War Department the morning of June 23. Sara Crouthamel, the youngest Chubb sibling, recalled being at home, having breakfast with friends on a sunny day.

"We automatically thought it was about Don, that he had been found," said Crouthamel, of Doylestown. "But it wasn't; it was telling us that Mary had been killed. That was quite a blow."

Few details ever emerged about Mary Chubb's death. On June 16, a single-engine, two-seat plane in which she was riding crashed at Ryton-on-Dunsmore, England, killing her and the Air Force lieutenant piloting the aircraft.

Where they were headed, and why, has never been explained to the family, Bob Estler said.

"The left wing tore off of a plane that was designed for aerobatics," he said. "So there was either a structural failure or this pilot was taking some chances."

Going home

On Sept. 2, 1945, Navy Signalman Dick McLaughlin watched from his nearby attack transport ship in Yokohama Bay as the Japanese formally surrendered aboard the USS Missouri.

It was time to go home, to families and hometowns forever changed.

He would find that his mother's hair, unstreaked by gray before her son's fatal flight, had gone completely white. His father threw himself nearly full time into building the new war-memorial athletic field on what is now the campus of Central Bucks High School West.

Eventually they arranged for Bud's body to be exhumed and returned from France. On May 15, 1948, the man once teased as a pacifist received a hero's burial in the military section of Doylestown Cemetery.

Reluctantly, Harry Chubb turned down a government offer to return his daughter's remains from England.

Ethel Chubb had suffered a stroke in 1946. It was likely a product of her grief, Harry wrote to the War Department, and he feared the stress a funeral here would inflict upon her.

Mary's body was instead moved from a temporary grave to a manicured military cemetery in Cambridge. The family used a portion of her small estate, most of it war bonds, to place a rose-hued granite memorial marker for Mary and Don in a rural churchyard outside of Doylestown.

"We hope that the sacrifices made in this war will not be in vain," Harry Chubb had written to an Army official in the fall of 1944. "Surely our love of peace and the uplifting of humanity should be much stronger than our love of those things that lead to war, destruction, and unending sorrow."

Others in Doylestown shared their anguish. More than 30 of its young people had perished in the war.

People like Jack Taifer, the three-sport high school star whose dad ran Ed's Diner, killed in a plane crash in England. And Gordon Kreutz, the gentle high school musician who died at 18 in Gen. George S. Patton's army. And Donald Myers, president of the 1938 senior class, killed with the infantry in France.

And too many others.

For those who did make it home, a postwar housing crunch loomed. Where would all these returning veterans live as they married and started families?

Within months of V-J Day, local veterans had formed an audacious plan to answer that need.

A grander idea

At first, VFW Post 175 was simply seeking a larger hall, as its postwar membership fast approached 700.

Its former commander, Col. George Van Orden, a veteran of the Spanish-American War and World War I, had set his sights on a 170-year-old farmhouse in what then was Buckingham Township.

But one day, as Van Orden looked out on the tract of strawberry fields, woods, and a stream, a grander idea struck him:

"Why not buy all 104 acres of the farm and build a brand-new community - exclusively for veterans?" a 1946 Inquirer story said. "Why not help Bucks County veterans solve their housing problems without waiting for government projects or private builders?"

In short order, the land was purchased, Philadelphia architect Fred Martin and landscape architect Thomas W. Sears were hired, and subdivided lots - typically a third of an acre - were offered for $400 to $800 each by the newly incorporated Veterans' Land Improvement Co. Vets who could not yet afford to build on the lots were encouraged to invest for later construction.

One skilled veteran built identical story-and-a-half homes on adjacent lots - one for his family, a second for a fellow veteran. Another craftsman, a Navy veteran, began renovating the farm's old wagon house.

But early lot sales were sluggish, at best.

Despite the need for housing, a shortage of building supplies, soaring inflation, and tightened credit were strangling the market. The land-improvement company's cash flow ebbed.

"Dissension had even crept into the post itself," according to one account in a VFW magazine.

In October 1947, local Realtor Bob Lippincott, a former infantryman, took over management of the enterprise, keeping it afloat as other veterans went door-to-door for donations.

A morale boost came Nov. 11, 1947, when the Kiwanis Club held a special Armistice Day luncheon in town. The names of Doylestown's war dead were placed in a container and drawn by the speaker, Navy Rear Adm. Thomas S. Combs.

The selected names would go on the street signs of the new veterans' neighborhood.

Soon, land sales rallied. The development company dropped its veterans-only restriction, and initial plans for a commercial strip, a movie theater, apartments, and a day-care center were scrapped.

Ten acres went to a Warrington developer, Joseph Barness & Son. It was one of the first projects overseen by young Herb Barness, a war veteran who would become Bucks County's dominant builder and a statewide Republican power broker.

The neighborhood, too, took on a name: "Maplewood," the winner of a poll taken of visitors to the site.

Its first six streets were dedicated on May 31, 1948. On a gray day of drizzle and downpours, Harry Chubb marched with a Knights of the Golden Eagle color guard in the borough's annual Memorial Day parade.

After ceremonies at the cemetery, the procession continued to Maplewood. A bronze memorial plaque was unveiled along South Chubb Drive, followed by a prayer.

"We came here today in pride," Col. Van Orden said, "rather than sorrow."

New arrivals

Ruth Hedrick, 81, still lives in the home she and her late husband built 56 years ago on South Chubb Drive, across from Maplewood's Veterans Memorial Park.

She reared four children there, back when children would still walk a mile to the borough school, and mothers could hear the reassuring toll of the lunch bell when the daytime breeze was right.

"It was a wonderful place for children growing up," she said. "The kids all played together because there weren't any fences. You never knew who was in your backyard."

Among those kids was Jeff Finley, 54, son of an FBI agent and today a Bucks County Court of Common Pleas judge. In the 1960s, Finley said, 35 children lived on his one-block stretch of Kershaw Avenue alone.

"It was bedlam sometimes," he said. "I was in the park playing baseball almost every night. You could always get a game together."

In those days, Doylestown schoolchildren still gathered flowers from their homes on Memorial Day and brought them to the borough school, Finley said. The kids then marched the cuttings to the American Legion hall, where volunteers took them to decorate the cemetery graves.

That tradition is gone, but Doylestown still honors the fallen; up to 20,000 people attend the Memorial Day parade each year.

Dick McLaughlin recalled a reunion he attended in Doylestown a few years ago. A friend introduced him to the bartender.

"He said, 'This is the brother of the man your street is named for,' " McLaughlin said. "Well, the guy kept pouring me old-fashioneds and wouldn't take any money."

Yet some believe it inevitable that, as younger residents arrive, knowledge of Maplewood's origins will fade.

"I just think that World War II may be out of their radar," said Frances Waite, 65, a professional genealogist who lives in Maplewood's original sample house on South Chubb Drive. "The average younger person has more recent wars to worry about."

A counterpoint can be found on the opposite end of Maplewood, at Walton and Miller Avenues. Megan and Jonathan Craig, both 26, were painting walls and moving boxes into their newly purchased home.

Jonathan, a pharmaceutical consultant, said they were attracted in part by Maplewood's mix of age groups.

Megan, a fifth-grade teacher, said that the couple had not known the story behind the street names, but that a family friend had told them.

"Now we know, and we're very, very proud," she said.

"I can't wait to move in."