VA clinic troubles bring few penalties

Despite poor care in the Phila. prostate program, the agency has only slapped a few hands.

More than a year after the Philadelphia VA Medical Center said it had given substandard care to nearly 100 veterans with prostate cancer, the list of sanctions is sparse:

One physician accepted a three-day suspension. A radiation safety official got a letter of reprimand. And the University of Pennsylvania doctor who performed most of the poor procedures lost his job when the Philadelphia VA closed the program.

Several lawmakers who have investigated the cases said that the Department of Veterans Affairs' actions were both anemic and late, and that the agency had acted only after prominent newspaper articles appeared in the summer, detailing radiation overdoses and underdoses.

"They ought not have to wait for a front-page newspaper article or a Senate committee hearing to do what they should have done on their own," said Sen. Arlen Specter (D., Pa.), one of the lawmakers who feels the VA has been slow to respond. "I think that it is regrettably necessary to keep pressure on them to follow up."

Newly obtained documents shed more light on the program, showing that the mistakes began with the earliest cases, starting in 2002, and that the hospital missed numerous opportunities to catch them.

In one 2003 case, for example, more than half the radioactive seeds landed in the patient's bladder instead of in the prostate. Yet no program-wide review ensued, and the brachytherapy treatments continued for five more years.

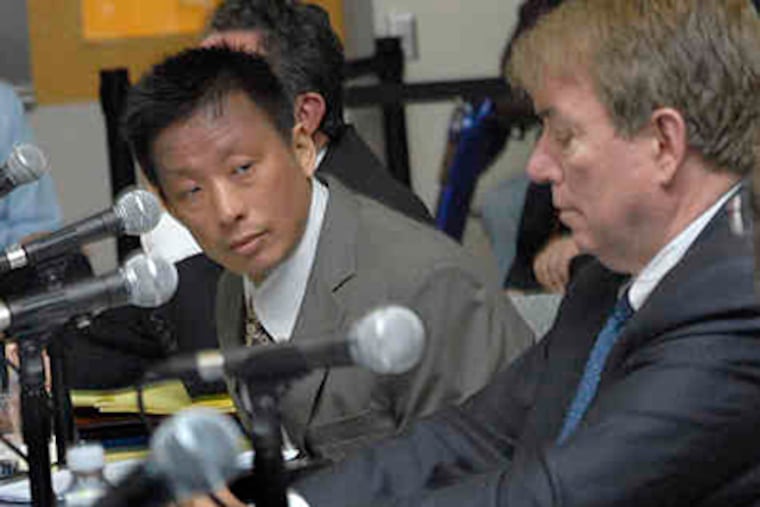

Gary Kao, the Penn radiation oncologist who directed the program, has been the public whipping boy for its flaws. He lost his VA position when the program was closed but was never officially sanctioned by the hospital. He's now on leave from Penn.

A whole team worked with Kao and shares responsibility for what happened, say investigators from the VA and other agencies.

So does the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which oversees the medical use of radioactive materials. The NRC reviewed several of the worst Philadelphia cases, including the 2003 case, and failed to stop the procedures.

From February 2002 to June 2008, the month the implant program was closed, 98 of 114 veterans treated got incorrect doses of radiation.

Federal investigators have found that 63 were underdosed and that 35 got too much radiation to tissue near their prostates.

The mistakes led to internal investigations, congressional scrutiny, and probes by the NRC and the VA's inspector general.

The NRC is expected to issue a report on the hospital's violations this week, followed by enforcement actions against the Philadelphia VA ranging from a violation notice to a fine of thousands of dollars.

At least five veterans have filed claims seeking compensation from the VA. The number is expected to rise since the VA has advised all the veterans of their rights to pursue legal action.

Gerald Cross, acting undersecretary for health at the Veterans Health Administration, and other officials ascribed delays to giving employees due process.

"Perhaps there were some missed opportunities" early on, Cross said, but he added that the agency had responded quickly when it identified a problem.

"We found it. We reported it. We took action" to stop the program, he said last month on his third visit to the medical center this year.

Cross said the VA was carefully monitoring the patients to ensure everything possible was being done for them.

Ten veterans have had a recurrence of their prostate cancer, according to the VA. And nine others show signs of a possible return.

Much of that may have been avoided if someone at the Philadelphia VA had been monitoring the quality of the implants performed by its team, led by Penn's Kao.

"There seems to be at least a couple patterns of a casualness about accountability," said Rep. John Adler (D., N.J.), a member of the House Veterans Affairs Committee. This month, he introduced a bill to require in-depth reviews of such programs across the VA hospital network.

From the first cases starting in 2002, the program was deeply flawed, according to new records obtained by The Inquirer. They show that the radiation in six of the first eight implants was far below accepted standards.

In two cases, the men's prostates got 39 percent of the intended radiation dose.

"These numbers are a surrogate for quality and whether you are actually doing it right," said Eric Horwitz, chair of radiation oncology at the Fox Chase Cancer Center. "You are really supposed to be looking at each one, but looking at them as a group tells you how the program is going."

Telltale case

One patient in particular shows how the VA team failed to monitor the program.

On Feb. 3, 2003, the brachytherapy team implanted its ninth patient. It had planned to put 74 radioactive seeds into his prostate, but a routine check after the procedure showed that 40 of the seeds had landed instead in the bladder.

"If you have a major episode such as this, it should mandate a review of all the procedures," said Gregory S. Merrick, director of the Schiffler Cancer Center at Wheeling Hospital in Wheeling, W.Va., and a nationally recognized brachytherapy expert.

Such a systematic review did not happen, according to medical center records.

After the errant seeds were removed from the patient's bladder, Kao "revised" his plan to the 34 seeds that were actually implanted.

After leaving the operating room, the patient would pass two seeds in his urine, leaving just 32. And a later calculation indicated that the patient's prostate got less than 17 percent of the intended radiation dose, records show.

Nine days later, on Feb. 12, the hospital's radiation safety committee reviewed the case.

The hospital's radiation safety officer, Mary E. Moore, concluded that it did not have to be reported to federal regulators because Kao had revised his plan before the patient left the operating room, the meeting's minutes show.

While NRC rules allow such revisions, medical experts say the flexibility was intended for small changes to adjust to circumstances discovered during the procedure, not to avoid notifying the agency and the patient of a bad procedure.

The committee disagreed with Moore and directed her to report the case to the NRC because "the variance between what was actually inserted and what was planned was too great," according to the minutes.

At the time, the NRC concluded that the case was not a reportable "medical event." By doing that, the NRC contributed to the VA's continuing lack of oversight. The nuclear agency's own staff would later recommend that the rule allowing such revisions be revised.

In June 2008, after the VA hospital identified the scale of the botched doses, the NRC reexamined that 2003 case and determined it had been a mistake.

But in 2003, the hospital's safety committee had decided to flag any future implants where 10 percent or more of the seeds were recovered from the patient. But the minutes show that even when two such cases were reported, no action was taken beyond continuing to "monitor" the number of seeds recovered in the operating room.

Then on Oct. 3, 2005, 45 of the 90 seeds implanted in an 86-year-old veteran were inserted in his bladder and had to be extracted.

Most of the seeds that remained in the patient ended up outside the prostate, including some near the patient's rectum, according to an expert who reviewed the case last year.

The patient reported significant pain in urination and was one of eight men the VA sent to Seattle last year for a reimplantation.

That case was reviewed, and the NRC was notified. Again the federal agency concluded it was not a reportable event for the same reason as before: Kao had revised his treatment plan.

The VA's own records - obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by The Inquirer - showed that the patient's prostate had received less than 30 percent of the intended dose.

Punishments

After the brachytherapy program was shut down last year, a VA Administrative Board of Investigation examined its many failings. In a September 2008 report, the board recommended that "appropriate administrative action should be considered" against several people who had key roles in the program.

But no actions were taken until late this summer after newspaper articles and congressional hearings.

The board recommended Kao be punished for failing to check his patients' dosing or help those who got incorrect doses. But Kao no longer worked for the VA and could not be disciplined.

The hospital paid Kao $188,428 in 2007, his last full year, VA records show.

Radiation oncologist Richard Whittington, who supervised Kao for much of his six years at the VA, has been the only doctor punished in the scandal. He was cited for knowing about the poor implants and not alerting administrators.

Last year, the hospital informed Whittington that it intended to limit what he could do at the hospital. The doctor opposed the action, his lawyer said, and the VA dropped the proposal this year.

Then after newspaper reports appeared June 21, the VA moved to suspend Whittington for 14 days for failing to supervise Kao properly. Again he objected.

The VA then proposed a three-day suspension.

"He agrees that there was not a robust peer review," Whittington's lawyer, Ronald H. Surkin, said. "He felt that he was one of the physicians involved, and he was willing to accept some responsibility for the lack of that program being in place, and on that basis he felt he could accept that proposal."

Whittington's three-day suspension was carried out in August. The radiation oncologist earned $180,641 from the VA in 2008, including a $1,500 "special contribution award" for good performance outside his normal work.

Moore, the radiation safety officer, was singled out for failing to train the program's nurses and doctors "regarding radiation safety" and NRC regulations.

But no disciplinary action was taken against Moore until last month after a reporter asked about her status. On Oct. 9, a letter of reprimand was placed in her file.

Moore's gross pay of $132,407 in 2008 included a $5,000 performance award for helping the badly treated veterans.

Moore did not respond to requests for an interview through the medical center or e-mailed questions.

Her supervisor, the medical center's associate director for finance, Margaret B. Caplan, who oversees radiation safety, said that "personnel actions . . . are considered confidential."

Joel Maslow, radiation safety committee chair, was not named in the report, but he presided over meetings in which the committee failed to fix deficiencies, according to the investigative board. No action was taken against Maslow.

In an interview, he declined to discuss any sanctions. He said that under his leadership, the committee had acted on issues that the board raised "even if that is not apparent in the minutes."

And he said the issues raised by the VA board had occurred shortly after he became chair in August 2006, when his focus was to "get the various factions" on the committee working together.

The VA paid Maslow $211,893 in 2008, including a $4,000 special contribution award.

Several members of Congress said the long delays and weak consequences set a bad precedent.

"Unless they are taking the recommendations and acting upon them, particularly if it means disciplinary action, then a message is being sent that it is OK," Rep. Joe Sestak (D., Pa.) said.

"A lack of accountable leadership is the source of the real problem here," he said. "Fixing it isn't just about putting better systems in place. It is also making sure that the culture of accountability is ingrained, and that is what is wrong with not taking these recommendations and acting upon them."

Philadelphia VA Implant Time Line

February 2002: The first prostate-cancer patient is treated.

February 2003: In the ninth patient treated, more than half the seeds land in the bladder.

October 2005: A patient, 86, gets half the seeds put in his bladder.

May 2008: A dosing error triggers a full program review.

June 2008: The program is shut down. Director Gary Kao stops treating patients at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania.

September 2008: Veterans Affairs' Administrative Board of Investigation recommends disciplinary action against several key people.

June 2009: Articles in the New York Times and The Inquirer detail a troubled program. Kao takes a leave from Penn research position. The first congressional hearing is held.

August 2009: Radiation oncologist Richard Whittington is suspended for three days.

October 2009: Radiation safety officer Mary E. Moore receives a letter of reprimand.

SOURCE: Department of Veterans Affairs, various sources EndText

INSIDE

Rough Start

From the very beginning, there were problems with the implants. Table, A18.EndText