Longing for success, battling demons

For young men like Leroy Lewis, escaping life on "the block" can be a frustrating effort.

Last of two parts

In early September 2008, Leroy Lewis paced the living room of his family's rowhouse in Juniata Park, restless.

Two months had crept by since he had been shot, the second time in less than a year. The recovering 19-year-old was eager for a future, but unsure how to move beyond his past.

Sitting home alone while his mother worked and his younger siblings were at day care or away for the summer, Lewis could peer out from behind the curtains and almost see the corner where he had sold drugs on and off since he was 16, hanging with his friends, and stuffing his pocket with $600 a day in wadded-up bills.

Surviving gunfire twice, he waited for his life to take some type of turn.

With his growing frustration, he shared many symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder with combat veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan - anger, flashbacks, hopelessness - though his free-fire zones were much closer at hand.

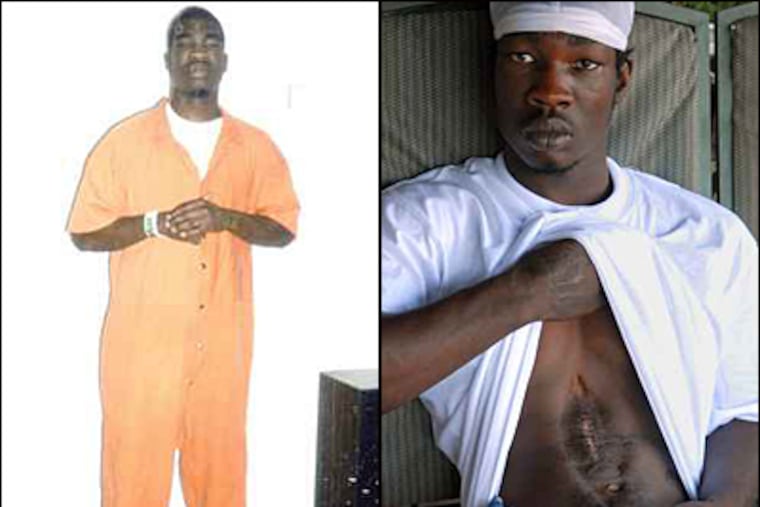

The previous September, Lewis, then employed as a housekeeper at the nursing home where his mother worked as a health aide, was shot in the stomach over an old drug debt. Ten months later, he was shot again, six times, another eruption from "the block."

He now wanted another life.

Walking the room, he talked of how he had gone from store to store on nearby Roosevelt Boulevard, looking for a job. He applied at Wal-Mart for a position stocking shelves, anything, he said. But when a letter came, he knew from the first sentences that he didn't get the job.

"I didn't even read the whole thing," he said. "I just threw it away."

He said he'd also inquired at community college about taking the SATs, and went to CHI Institute, a trade school, with his high school diploma tucked under his arm, for an application. "They still haven't called back yet."

His limp from the recent shooting was noticeable. He patted the hard knot in his abdomen from the first. His doctor said he might develop a hernia.

"Why can't I get a job?" he wondered. "I got a diploma. I'm not a dumb kid, and I can't even get a job if my life depended on it."

To a prospective employer, Lewis lacked promise.

He had no driver's license and little job experience. A month after his 18th birthday, after a brawl in a juvenile placement facility, he had pleaded guilty to simple assault and got probation, the first mark on his adult criminal record.

Now, in searching for a job, Lewis had plenty of company.

At 19, he was a member of a group of black youth throughout the country for whom unemployment hovered at 35 percent. By fall, as the economy spiraled, the number would rise to 50 percent.

Lewis had all but given up on Tinisha Scott, a case manager from PIRIS, the Pennsylvania Injury Reporting and Intervention System, a pilot initiative created to help young gunshot victims put their lives back together.

Lewis said Scott had canceled appointments; Scott said Lewis hadn't returned calls and often wasn't home.

"Leroy had a lot of potential," Scott later said, noting his high school diploma. "He'll talk a good game, but he's going to die in these streets, God forbid, or get locked up. He didn't learn his lesson."

As Lewis paced the room, he did not yet realize that he had been dropped from PIRIS, labeled "unable to continue engagement," a term case-management supervisor Doris Spears said is used for hard-to-reach clients.

According to PIRIS data, of the 332 gunshot patients whom hospitals referred to the program in its three years, only 56 percent were enrolled. The remaining victims either refused help when contacted by caseworkers or could not be contacted.

Lewis' relationship with his mother was also strained. Tired from work and stressed over bills, she had been complaining about his idling around the house.

"She in here putting a burden on my shoulders knowing I can't do nothing," he said. "I'm sitting here looking like a dummy 'cause I ain't doing nothing, just waiting, watching TV, and going to the bathroom."

He paused, reasoning.

"I be trying, but I can't sit here and argue with my mom about not having a job, because I should have a job. It's me, too, because when I do try and it be like a no-go, I just go right back to the block. Then when I get tired of the block, I try again, and it don't work, and then it be like . . ."

Lewis let out a scream.

If he sat in the house, his mom was mad. If he did "the block," his mom was mad.

The first made him feel like a lesser man. The second was just outside his door, waiting.

"It's the only thing I really know," he said. "That's what I fall back to. If I can't get a job or do something else, I'm doing the block."

Staring out the window, Lewis reminisced about his stint at the nursing home, his brown uniform, the pride of having somewhere to be in the morning. He had the job only a month before he was shot in the stomach. When he was unable to walk or eat after surgery, his employment ended.

"I know this ain't nothing," he said, throwing his arms up at his days now.

"I want to be good. I don't want to be 25 and out here pitching nicks and dimes. Why I want to keep doing that? Change the plan. I want to see me in my real estate business. I want to see me progressing, that's all."

A maternal ultimatum

Sitting at her dining room table on her day off, Paulette Lewis, 41, a soft-spoken woman with tired eyes, searched for answers.

Two weeks earlier, she had issued an ultimatum, and Lewis moved out, back to the block.

Maybe her son was troubled because she was a single mother, she thought. Maybe she spoiled him. Maybe she wasn't stern enough.

"I don't know what went wrong," she said, tears in her eyes.

While doing the laundry, she had found marijuana in Lewis' pants pocket.

She had stood over him, as he sat on the couch watching TV, and demanded: "When are you going to get off the street and do better?"

"I'm trying," Lewis had said.

"You're not trying hard enough! You cannot be here if this is what you're going to do."

Lewis had run upstairs and slammed the bathroom door. Her daughter came down and told her he was crying.

Paulette Lewis had gone to him, and begged, "What's wrong?"

"I'm trying," he chanted. "I'm trying."

In his own way, she knew he was. But over the summer, she had watched his efforts wane.

"Leroy knows he's doing bad, and he wants to do good, but he don't know how. He just got caught up in the wrong crowd. I told him, 'You need to keep trying. You just don't give up like that.' "

She tried to be an example, offering him her struggle - as a mother of five who worked full time - to become a registered nurse, of failing the test, of continuing to try.

"He's very frustrated," she said, her hair wrapped in a black scarf. "He's afraid of failing."

Shortly after their argument, Lewis again made his choice. He moved out, back on the block.

A few days earlier, while driving through the neighborhood, the tassel from his graduation mortarboard hanging from her rearview mirror, she spotted him standing on a corner.

Lewis stared at her, blankly. Then he smiled.

"My heart breaks," she said, her voice trembling, "because I don't know what kind of trouble is going to happen out there with him."

Her tears continued to fall.

"I feel as though I'm going to have to bury him soon."

Everyone's fears realized

By October 2008, everyone's fears for Lewis had caught up to him.

One night, Amy Goldberg, chief trauma surgeon at Temple University Hospital, pulled the curtain back in the trauma bay and found Lewis stabbed twice in the back.

Goldberg had stitched and stapled together Lewis' stomach after the first shooting and had pushed PIRIS to enroll him after the second.

Lewis refused to talk to her about the stabbing. She noticed a cold change in him, from the cooperative teen who before had called her Miss Amy.

"I just again felt terrible," Goldberg remembered, "that we had failed him in some way."

The stabbing, Lewis later explained, was over his girlfriend. Standing with her on a train platform earlier that day, Lewis had confronted a young man who'd supposedly flirted with her days before, behind Lewis' back.

Their exchange ended with Lewis' hands around his throat. With the fight over, Lewis was counting change for the fare when he felt something warm prick his back.

Before he could turn around, he felt it again. He dropped the coins in his hand. As he turned, he saw the young man he had choked, his attacker, running out of sight.

Two weeks after the stabbing, at 4:30 one Monday afternoon, according to police records, two brothers, 17 and 19, were talking with a younger friend near an alleyway behind a stretch of houses in Juniata Park, a block from where Lewis had been shot the second time. Two cars, a burgundy sedan and a white Cadillac, cruised through, their passenger windows down.

All of a sudden, the brothers heard five, six gunshots and saw flashes of light coming from the sedan.

The brothers dropped to the ground, unhurt.

The motive is still a mystery.

Police later learned from a witness that one black male exited each car and started "shooting at the complainants."

The bullets missed.

When the shooting stopped, the brothers ran home, and the cars peeled off.

Three witnesses identified Lewis and one of his older brothers as the shooters, "enough probable cause to issue a warrant," according to the police report.

Lewis' brother was quickly arrested for attempted murder. Lewis fled to his grandparents in Brooklyn, "out of fear for my life."

Lewis had been candid about most aspects of his life during this time, but when it came to the shooting incident, he offered nothing. He wouldn't acknowledge his, or anyone's, involvement, or even hint at which slight, debt, or feud might have precipitated the event, likely honoring the code of the streets he had gambled in.

In Brooklyn, as his grandparents' home sat dark and quiet at night, his grandmother noticed Lewis pacing the hallway and mumbling to himself.

"I couldn't eat. I couldn't sleep," Lewis recalled. "The walls were closing in."

When he did venture out, he saw "evil in people's faces," so he retreated inside.

He kept replaying the two shootings. He worried about his brother locked away in jail. And now he was alone, hiding. Reality was slipping.

"I was hearing voices," Lewis continued, his eyes wide. "Everything everyone ever said to me came back."

Go to school. Keep busy. Stay off the street. What are you doing with your life?

"I jumped out of my skin," he said. "I was breaking down."

His grandmother called his mother to collect him, as her husband had done summers before when he couldn't deal with Lewis' behavior. On the drive home, his mother noticed that Lewis was "seeing" things out the window that weren't there, and she took him straight to the Fairmount Institute, a psychiatric hospital. He stayed a month.

Doctors prescribed anger-management classes and medication. According to Lewis and his mother, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. However, several mental-health experts who have studied the effects of gun violence, including Paul Fink, a psychiatry professor at Temple University's School of Medicine and chairman of the city's youth homicide committee, say that the diagnosis is overused and that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is more likely. Its symptoms include flashbacks, anger, avoidance, hopelessness - and hearing and seeing things that are not there.

"His symptoms and his actions are not accidental or consistent with a new onset schizophrenia," said Annie Steinberg, a clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

Instead, Steinberg said, the visions and voices inside Lewis' head were likely caused by PTSD or "untreated depression with psychotic features," caused by being in the crosshairs of violence, shot twice, and stabbed.

"They are all related to the events that occurred. These are not random paranoid delusions. They are thoughts of regret."

On Feb. 16, 2009, the day Lewis was discharged from Fairmount, his mother took him to the 35th Police District, at Broad and Champlost Streets, to turn himself in on an open warrant for attempted murder in the October shooting. Charges against his brother had been dropped weeks earlier, when, after several preliminary hearings, none of the witnesses appeared in court.

At the station, according to the police report, Lewis lunged at arresting officers Matthew McCrea and Gerard Winward, and yelled, "Boom!" Lewis said he shouted, "Boo!"

The Police Department declined to comment on the incident, and Lewis has been unable to explain his behavior. However, his mother remembered telling officers that he had just been released from a mental hospital.

Because Lewis had "struggled" with the officers, according to the police report, added to his attempted-murder charges were simple assault, aggravated assault, reckless endangerment, and resisting arrest.

Unable to make the 10 percent bond on his $75,000 bail, Lewis, 20, was transferred to county jail.

Months in jail

In late April, after two months at the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center, on State Road, Lewis, sitting in the visiting room, wearing an orange prison jumpsuit, seemed thoughtful, calm. He smiled often. His face was fuller. His dreadlocks were gone.

"I just thank God I'm still here."

Awaiting his preliminary hearing on attempted-murder charges, he said, he had spent his time watching the news, playing basketball, scoring in the card game Casino, and reading a Bible in his "hut," a cell he shared with another inmate. Once a week, he attended Bible study.

With his prison case manager - the city's social-service provider of last resort - he had set immediate goals for if and when he was released: Get a driver's license, get his stomach checked. Most important, find a job.

"Why didn't I do these things sooner?" he said.

As he pulled a Jolly Rancher candy from his white sock, he talked about lessons learned.

"I believe, every day, you have a chance to walk down a straight path. I realize now that taking one wrong turn just leads to another."

Within the concrete walls, even his dreams had found limits. He believed that, until he found a job, he could easily work a hot-dog stand on Broad Street in summer, shovel snow in winter.

"There's a thousand hustles out here. I can hustle anything, something positive. I've always been an entrepreneur."

He saw real estate in his future and considered going back to Brooklyn to learn the business from his grandfather. Although part of him wanted to find his own way.

His friends had been a disappointment - none visited him in jail.

"She's my true family," he said of his mother. "She worked hard for me. And I see she was so right about everything."

In May, prosecutors withdrew the charge of attempted murder against Lewis. For the third time, no witnesses had shown up at his preliminary hearing.

Lewis later pleaded guilty to the resisting-arrest charge, the lesser of the related charges, and was released on six months' parole, less time served.

On July 1, having lost its state funding, the PIRIS program shut down, leaving a bigger void for gunshot victims like Lewis.

A summer of trying

Lewis spent the summer at home, seeing doctors, eating his mom's savory cooking, and thinking about what was next.

He was nervous about going out and hated riding the bus, being anywhere there were crowds. His therapist, whom he saw every other week, told him he might be experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder.

Lewis bristled whenever his mother stuffed money in his pocket, even for the smallest thing, like a pack of cigarettes. She urged him to be patient as he grew ever more eager for a job. He later considered enrolling in Job Corps, a free federal education and job-training program for youth.

His mother also contemplated change. "I have to stop bringing up his past," she said. "I have to give him a fresh start. How can he change if I keep bringing up his past?"

Lewis thought a lot about his father, whom he hadn't seen since he was 3. With his parole completed, he considered the possibility of visiting him in Jamaica.

"I just want to be able to meet him," Lewis said. "I got a lot of questions, like, 'What happened? Why were you never there? And what would you do to change the situation, to try to work something out where you're in my life?' "

By mid-September, two years after Lewis had first been shot, his life had come full circle. On a mild Thursday afternoon, his mother came through the front door of their Juniata Park home, cradling bags of groceries.

As she put the food away, his sister sat in a chair in the living room, pencil in hand, biting her lip over her homework. On the other side of the modest room, his brother and a friend pointed and laughed at the television. And within the pace, within the din, Leroy Lewis sat on the couch, his head down, staring into nothing.