Keeping officers' unauthorized crime-scene photos from going viral

Shortly after 10 a.m. on July 11, 2008, police and ambulances arrived at a crash on I-95 in Philadelphia to find an uncommonly gruesome sight.

Shortly after 10 a.m. on July 11, 2008, police and ambulances arrived at a crash on I-95 in Philadelphia to find an uncommonly gruesome sight.

With five cars scattered in wreckage across both sides of the highway, traffic near the Bridge Street exit was at a standstill. A pickup truck lay in the northbound lanes, its windshield shattered. A short distance away was 50-year-old Ferdinand Ramirez Villaneuva, whose head had landed about a dozen feet from his body.

Even for veteran police officers, seeing a dismemberment up close is unusual - so unusual that one officer snapped a grisly photo of the mutilated body with his camera phone and sent it to someone. It's unclear how many others saw the photo, but eventually it traveled to people who have no connection to the accident, or to the man who died.

It's nothing new for police to take photos with personal cameras. Some veteran officers keep scrapbooks, and some detectives used to carry cameras to snap pictures of scenes before the Crime Scene Unit arrived, just to ensure that nothing got moved.

What has changed is the technology and the way people exchange information. Camera phones make it easier than ever to distribute images, and officers can instantly forward pictures to colleagues, friends, or family. Sending a photo via cell phone means the sender loses control of it and, from that point, has no way of knowing where it will end up. In one case, family members received a photo of a relative's dead body, and according to law experts, a photo landing on the Internet or in the wrong hands could have legal ramifications.

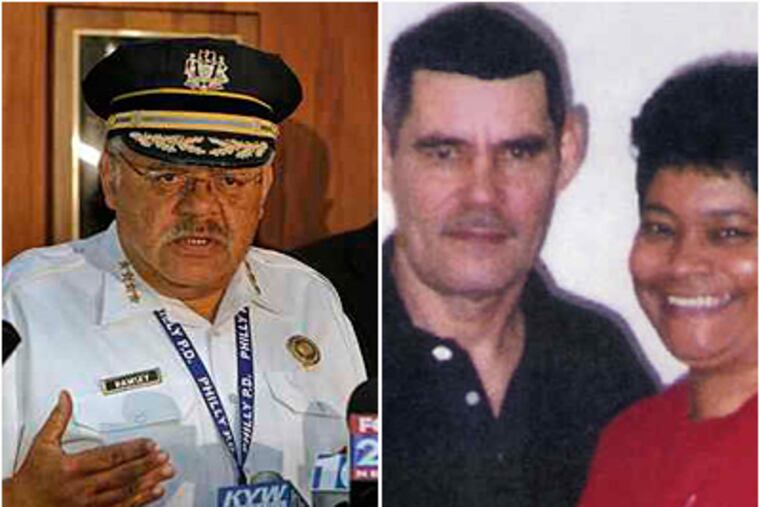

Police Commissioner Charles H. Ramsey condemned the taking of personal photos at crime scenes, calling it unprofessional and immature.

"I think it's pretty sick to take pictures of crime scenes when it's not part of your job," Ramsey said. "It's ghoulish. And I can't figure out why you would want to remember some of that stuff. It's bad enough that you have to see it in the first place."

The department's guidelines forbid officers from using personal camera phones to document scenes or evidence. But whether due to a morbid fascination, a genuine interest in crime-scene photography, or a desire to keep souvenirs from on-the-job experiences, some officers say, it happens all the time.

Short of confiscating officers' cell phones, the department can do little to prevent picture-taking. But Ramsey said any officer caught doing it would be disciplined. He declined to elaborate, saying that the punishment would depend on the circumstances and that officers who forward pictures sent by others were subject to the same rules.

"Even if you didn't take it, you shouldn't forward it," he said. "You shouldn't add to the problem."

As camera phones and mobile Web-browsing have become ubiquitous, police organizations across the country have started adapting their policies to keep up with technology. The Washington-based International Association of Chiefs of Police issued guidelines last month on how officers should use social-media sites such as Facebook and Twitter, but there was no mention of cell phones.

Officers have been caught sending inappropriate cell-phone pictures in a handful of police departments elsewhere, including New Jersey, where a Sussex County appeals court in March upheld the 30-day suspension of an officer who sent a photo from a murder-suicide investigation to a friend.

In addition to being a violation of department guidelines, Ramsey said, the behavior is demeaning to victims and their families. "Would you want someone taking a picture of one of your loved ones?" he said. "These guys need to think about that."

Ramirez Villaneuva and his wife, Anna Torres, were on their way home from the supermarket on that morning in 2008 when an out-of-control Chevrolet Monte Carlo smashed into the back of their pickup truck at an estimated 80 m.p.h.

The crash, which according to police was caused by a New Jersey man who was high on morphine, sent Ramirez Villaneuva's truck crashing into the center barrier. The truck flipped into oncoming traffic, throwing Torres from the car, and ejecting Ramirez Villaneuva through the windshield.

Torres, whose skull was fractured in the accident, learned last week that a picture of her husband's body was taken and sent to others after the crash.

"I don't understand," she said in an interview in her Kensington home, speaking in Spanish, her eyes filling with tears. "People saw it, but we didn't see it?"

Torres now struggles to pay her bills and, for months, suffered from headaches as a result of her injuries. Her son, 30-year-old Ferdinand Ramirez Jr., said that if Torres had somehow seen the photo, it could have brought on an asthma attack.

"I don't know why they would do that," Ramirez said. "Why did they do that?"

Investigators from the Crime Scene Unit have the official task of taking evidentiary photographs after a crime has taken place, documenting every inch of a scene.

But last summer, after a local newspaper got hold of a photograph of skeletal remains, it came to Ramsey's attention that others were taking pictures on the job. An investigation revealed that an officer was responsible, said Anthony DiLacqua, chief of the Internal Affairs Division. That officer was disciplined, though DiLacqua would not specify how.

In September, as a result of the incident, Ramsey added a directive to the department's guidelines, prohibiting the use of privately owned cameras or other devices to record scenes or evidence while on duty.

But if it's hard to stop officers from taking pictures, it might be just as hard to catch them. Asked how many officers have been investigated for taking crime-scene pictures, DiLacqua could think of only one.

The case of Daniel Giddings, who killed Officer Patrick McDonald in September 2008 before he was shot by police, provides one example of how fast a camera-phone picture can travel.

In the hours after Giddings was shot by police in North Philadelphia, a picture of Giddings' bloodstained, lifeless body circulated rapidly through the Police Department's cell phones. Again and again, people hit "send" until the image spread beyond the police force.

One sergeant's mechanic received the picture. A lieutenant returned home to find someone had sent it to his teenage daughter. And soon enough, members of Giddings' own family received it on their phones.

Giddings' mother, Theresa Bryant, said no one in the family recognized the phone number attached to the picture. But they assumed a police officer was behind it.

"I guess they got a thrill out of it," Bryant said. "They might have thought it was funny that he was laying there dead on the ground. But it wasn't funny to me."

Because Giddings died, there was no ongoing investigation into McDonald's death. But legal experts said photographs of evidence in an open case, such as the accident that killed Ramirez Villaneuva, could have a legal effect.

L. George Parry, a defense attorney who formerly headed the police corruption unit for the District Attorney's Office, said cell-phone photos could create trouble for prosecutors if they became public.

"It certainly could raise questions for defense counsel," he said. "As an attorney, you want to get every possible picture of a crime scene, and usually people try to control those scenes for that reason. If you have these 'freelance' photographers running around, it may turn out that there are things in these pictures that don't fit the prosecution's case."

Parry knew some Philadelphia officers who took pictures of scenes in the 1970s, some of whom seemed to do so out of apparent amusement or scorn for the victim. But Parry speculated that many officers who take pictures may not do so maliciously, but in a misguided attempt at processing a disturbing reality.

"Officers get desensitized to the not-nice aspects of life," Parry said. "A few short miles from where you and your family live, you're plunged daily into this world where terrible things happen. It's very disorienting, and to react like this may be a type of coping mechanism."

Whatever the reasons, Parry said, the behavior is basically impossible to control.

"You can't stop cops from sleeping on the job, you can't stop cops from going into a bar and having a few nips while on the job, but you try to enforce these things," Parry said. "There has to be some sense that this isn't acceptable.

"It really goes to the professionalism of the department," he added. "It makes them look very bad. That dead body there was somebody's loved one, and people are entitled to a little more dignity than to be used as objects of entertainment."