Sociologist chronicles tenuous lives of fugitives

For a sociologist, the value of field notes can't be overstated. Yet Alice Goffman felt deep relief at destroying hers - shredding the notebooks, then disposing of the hard drive kept in a safe-deposit box under someone else's name.

For a sociologist, the value of field notes can't be overstated. Yet Alice Goffman felt deep relief at destroying hers - shredding the notebooks, then disposing of the hard drive kept in a safe-deposit box under someone else's name.

"That was a nice day," she said, "when the threat of being subpoenaed for my field notes was gone."

That threat was among the lesser perils of being embedded in a network of young men who lived, on and off, as fugitives for crimes ranging from the petty to drug dealing and shootings.

Goffman, 32, spent six years with the men and their families in a poor, minority Philadelphia neighborhood she calls Sixth Street to protect its identity. She began the work in 2002 as a University of Pennsylvania undergraduate, becoming so immersed she nearly lost herself in the process.

She adopted the men's survival tactics: the art of fleeing through alleyways, the grit of enduring interrogations. Back at school, though, her heart pounded at the sight of clean-cut, white (in short, coplike) professors.

By 2004, she writes, "The likelihood that I'd soon go to prison seemed about equal to the chance I would make it to graduate school."

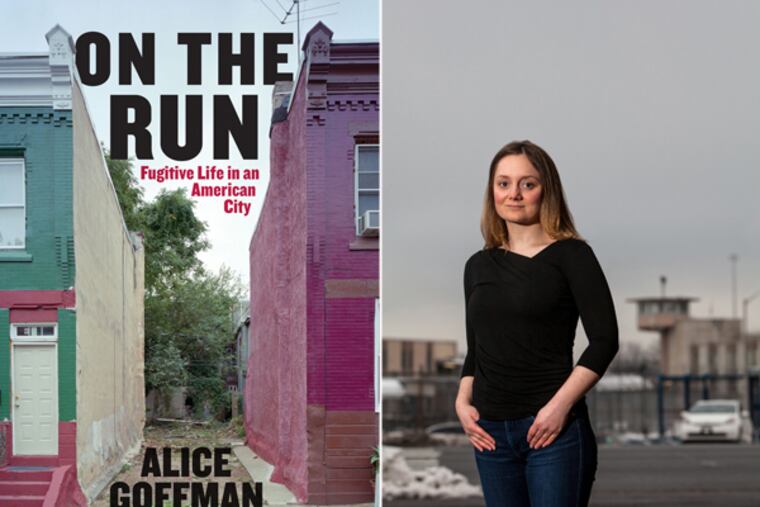

That spring, she was accepted to Princeton. And this month, her book, On the Run: Fugitive Life in an American City, will be released by the University of Chicago Press.

It's an on-the-ground account of the effects of a U.S. prison boom that, paired with stringent policing and surveillance efforts, has incarcerated one in nine young black men.

It documents how the criminal-justice system, and efforts to evade it, have woven a new social fabric. Even identities are defined in the neighborhood by police interactions: People are "dirty" (with an open warrant) or "clean"; "hot" (drawing police) or "cool"; "a rider" (one who aids a fugitive) or "a snitch."

Goffman grew up in Center City - like many white Americans, unaware of how places like Sixth Street were being transformed by mass incarceration.

But as an undergraduate, she began tutoring a teenager named Aisha (a pseudonym, like every name in the book), and spent more and more time in Aisha's community.

As the young men there accepted her into their circle, she gained entree into the messy, difficult world that is life on the run. She bailed the men out, visited them in prison, and spent long nights driving around with them as they sought to avenge a friend's death. She also endured police sexual harassment, violence, and destructive late-night raids, she said.

For poor minority communities, that's the norm, said Goffman, now an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"The way police sometimes see . . . the young men I'm writing about, it's very much this level of dehumanization. It's akin to what you see in accounts of two sides of a war," she said.

And those men weren't outliers: In 2009, before the advent of tough-on-crime programs such as bench-warrant court, Philadelphia had 47,000 fugitives. Paranoia, she discovered, framed daily life: Men avoided hospitals because police watched the visitor logs; they skipped friends' funerals because they, too, were surveilled. (It also fueled an informal economy: In a crisis, a fugitive would rather pay a hospital janitor for treatment than go to the ER.)

And it transformed interpersonal and romantic relationships. Even for low-level warrants, police tried to extract information from girlfriends and mothers, threatening eviction or loss of custody, she said.

Women sometimes used their role as informants to punish the men (one of many ways people have co-opted the system for their own purposes).

Lt. John Stanford, a police spokesman, called such descriptions of systematic violence and intimidation "ridiculous." He added, "It's absurd to even think that we would tolerate something like that."

But Yale sociologist Elijah Anderson, Goffman's undergraduate adviser at Penn, said her work was an important and revealing contribution.

"We like to think we're a democracy: We don't do these kinds of things. We don't surveil young men," he said.

"It seems to be going beyond the call of duty. You don't violate another person's life before you have rightful cause, and it seemed like the cause wasn't there in a number of cases. It was, I think, overreach."

By the time Goffman left Sixth Street, she was displaying symptoms reminiscent of post-traumatic stress disorder, such as panicking at sudden noises.

For residents, she said, there's no "post": "It's just traumatic. This is everyday life: a series of ongoing and acute traumas."

For the men, there seemed to be few options for becoming "clean." She watched as one, whom she calls Chuck, was rejected for dozens of jobs after his release before resorting to selling drugs.

"Chuck would be cutting crack, and he'd say, 'I . . . hate this.' It ruined his mother and so many of his friends. To him, it was work of desperation."

Goffman never expected the book to gain traction beyond academic circles. But in April, there was a bidding war for trade paperback rights. "There's been this huge shift in the conversation in the last few years," she said. "Before, people were not seeing this as a civil rights issue." Now, the president is talking about rolling back mandatory minimum sentences.

David Rudovsky, a civil rights lawyer and former public defender in Philadelphia, said the consequences of policing tactics can be seen in the flood of men being jailed for technical parole violations, such as missing a curfew.

He also cited arrests over small amounts of marijuana: 90 percent of those arrested are racial minorities, though studies indicate just as many whites use the drug. "That kind of disparity, explainable only by race, that's a civil rights issue," Rudovsky said.

David Grazian, an urban ethnographer at Penn, said exposing these differences required "extraordinary bravery, compassion, and commitment to scholarly enterprise."

Goffman admitted her background "may have pushed me to go further than was safe or expected."

Field work is in her blood: Her late father was famed sociologist Erving Goffman; her mother and adoptive father, Gillian Sankoff and William Labov, are both noted sociolinguists.

Still, she said, "In some ways, I didn't go far enough. The facts of my identity prevented me from going there. I didn't get arrested and convicted and go to prison. Maybe that will be my next field of study - if I can pull it off without losing my job."

215-854-5053 @samanthamelamed