A year into his job, Atlantic City mayor somehow keeps smiling

ATLANTIC CITY - Well, that was some year. What can you do when you became the mayor of Atlantic City in 2014 except somehow embrace the madness?

ATLANTIC CITY - Well, that was some year. What can you do when you became the mayor of Atlantic City in 2014 except somehow embrace the madness?

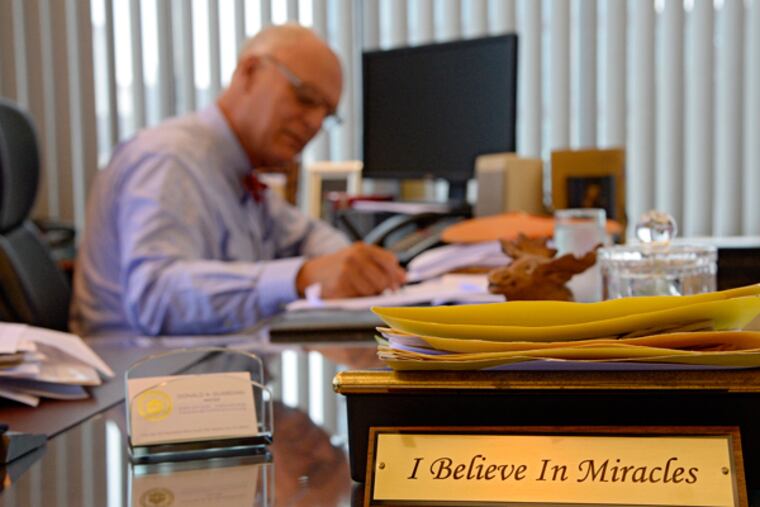

"It's a strange town, I'm a strange mayor," says the improbably still cheerful Don Guardian, who reaches his one-year anniversary as mayor of America's strangest resort Jan. 1, four casinos down, 8,000 more people unemployed, countless pronouncements that his town is dead or dying.

"It's a perfect fit," he says, and the funny thing is, he means it.

But wait. Before any mayor of Atlantic City can even think about contemplating the long view, there is the problem of the next 10 minutes.

If this is real-life Monopoly, and, actually, it is, maybe more than ever, most of Guardian's property cards are currently turned over, there's no money stuck under his side of the board, and he keeps landing his top hat on streets where he owes money to hotels.

But on this late afternoon in the seventh-floor office that looks out to the Trump Taj Mahal (letters mostly still lit), Guardian can - a minor miracle - say how the city will make it to 2015 without the game ending.

It involved last-minute moving pieces: Wells Fargo agreeing to pay off $26 million of bankrupt Revel's $32 million tax bill, an anonymous bidder agreeing to take care of bankrupt Trump Entertainment's $22 million tax bill, and the final piece - the state of New Jersey acting as banker, giving the city a short-term, $40 million loan at a forgiving rate. Pass go, collect $200.

So, the city will - just barely - make it to 2015, and this genuine, bow-tied, open-door 61-year-old Republican mayor with a year under his belt seems neither shell-shocked nor in need of a year in a spa to recover. (Conveniently, his husband, Louis Fatato, is a spa manager at Borgata.)

"We don't know any better," Guardian said, laughing. "We haven't had good days."

But he is a relentless optimist, up for a challenge, and he sees the casino meltdowns accelerating a post-gaming vision he had for A.C. going into the job.

"I didn't think I would have this opportunity to change the city as quickly as I have," he says, and though it sounds like a punch line, he means it.

"I thought it would be much tougher to convince people that gaming was not in our best interests," says Guardian, a North Jersey native who previously headed the city's Special Improvement District. "That it was important - we don't want to kill it - but we want to move away from it. When I was talking like this last year, people were kind of nodding and telling me it was an interesting concept. This year, everyone is willing to move."

He sees tectonic shifts under the ruins: the closings on his watch of the Atlantic Club, Showboat, Trump Plaza, and the ultimate problem child, Revel.

He sees tantalizing interest from Philadelphia developers like Bart Blatstein, who bought the Pier at Caesars, and LPMG Properties, redoing historic Morris Guards Armory into urban-style lofts. He sees a "new Atlantic City" in young entrepreneurs who run slightly off-the-radar places to eat and drink: Perfectly Innocent Amusement Co., the Iron Room, and Tony Baloney's, which despite being in no-man's-land in Revel's shadow, still has a line for lunch.

There are 500 housing units being built, Stockton's Island Campus coming to Showboat, a deal close for the Atlantic Club.

He believes he is the man for the moment. "I'm a strange fit to be the mayor," he said. "I think it's the perfect fit."

'I brought a palm branch'

That's a case he's trying to make to Gov. Christie, whose advisers proposed a powerful emergency monitor to run the city instead of the mayor.

Of all the crises, closures, downgrades, and dead deals cascading into the Mayor's Office - and his is the main number listed for City Hall, so aides Jazmyn Rivera and Linda Garlitos hear it all, like goalies redirecting, blocking, and saving shots all day long - this one stung.

"Yes," he says when asked whether he took the emergency manager idea personally, only months after voters played an unexpected card by electing him over entrenched Democrat Lorenzo Langford, who had been mayor for nine of the previous 12 years.

Guardian is still trying to head the emergency manager idea off, buttonholing Christie at a holiday party, awaiting a formal audience, proposing deep cuts and asset sales favored by managers in Michigan, the state's model.

He says he has already brought in non-political technocrats favored by state oversight. "I was the least political guy in the city," he says. "I didn't bring boxing gloves when I came into this office, I brought a palm branch."

Potential for $120 million a year

"If this was a normal year," says Guardian, sitting in a chair in front of his desk, "I'd be doing a year-end saying, 'You know what? We reduced crime, we reduced use of force, we're cleaning our streets every day where we used to clean them every two weeks.' There's no neighborhood I go to that I say, 'Isn't public works doing a great job?' that people don't applaud."

Guardian embraces state legislation that could be voted on in January that would lock in a collective $120 million-a-year payment from the remaining casinos - which in this apocalyptic era are calling themselves "the survivors." It would redirect other casino taxes to pay off city debt. Although casinos were taxed $210 million this year, Guardian declares the $120 million fair (he knows it sounds "like highway robbery"), factoring in lost taxes from closed casinos (about $64 million) and a fear of even steeper drops from appeals or reassessment.

Most of the debt is owed to Borgata, which won $88 million in tax appeals. The previous administration nixed an offer from Borgata to settle for a fraction of what it then won in court. Despite inheriting these decisions, Guardian refuses to assign blame. "I'm just fixing what's there," he says.

Guardian plans a $40 million budget cut over four years. He cut 140 jobs by "aggressive attrition" and plans to eliminate at least 100 more through layoffs. He plans to consolidate, privatize, or cut a half-dozen departments. He pulled 70 city vehicles off the street.

City assets mentioned for lease or sale: Garden Pier, Comfort Station at Kennedy Plaza (paging La Colombe), Gardner's Basin, and Bader Field, the old airport for which the city turned down $900 million only seven years ago. That's how steeply the landscape has changed.

Even after he raised taxes 29 percent, "People have been warm and friendly." In turn, he apologizes "for the pain we're going through." He's not worried about a recall try, a typical A.C. maneuver.

In winter, the morning Boardwalk bike rides became two-mile walks to work, a new route each day. He has no regrets. He's not hiding, not even behind his desk. Anyone can still schedule time with him, though now it can be two months out.

"I love my job," says Guardian, who makes $103,000, having forgone a $15,874 raise approved for his predecessor. "This is my favorite job."

Still, he knows how it looks. Another day, another obit for Atlantic City.

"I know," he says. But his eyes light up. He's got the right metaphor.

"So here's what happens," he says. "There's no doubt I've become captain of the ship. The question is, am I steering the Titanic or am I steering the Ark? I'm telling you we're going to make landfall."

In the waning light, chief of staff Chris Filiciello looks over. "And you've got two of every kind," he adds - as in only in A.C., with a cast of characters like none other.