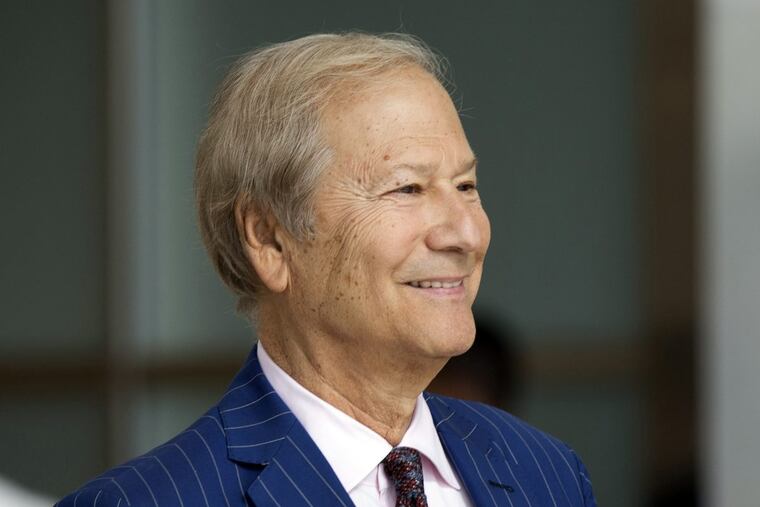

Lewis Katz, of South Jersey, left a permanent mark on business, media, and medicine

At points along the way, owning the NBA's Nets, the NHL's Devils, a plane, a yacht, he'd stop and marvel: "Who would have thought that a kid from Camden …"

Lewis Katz stood 6-foot-2, taller than many contemporaries.

He towered in the Philadelphia region, too, earning and giving away millions of dollars, touching nearly every aspect of life from education to sports, from medicine to politics.

Katz, a lawyer, was at points the owner of the NBA Nets and NHL Devils, and of Kinney Parking Systems when it was the largest parking company in New York City. He was chairman of the billboard firm Interstate Outdoor Advertising, the majority owner of five radio stations on the Jersey Shore, and an owner of the company that became Philadelphia Media Network, which operates the Inquirer, Daily News and Philly.com.

Today, three years after Katz's death in a plane crash in Massachusetts, those close to him remember less what he had and more what he did — and maybe most of all how he did it.

It's no exaggeration to say that Katz, a vigorous 72 when he died, started with nothing and created his own way forward.

"Lewis believed that if he followed the path that has been followed by others, that it wouldn't work for him," said his friend and lawyer Stephen Harmelin, a corporate law specialist at Dilworth Paxson. "He was one of the most intuitive business people I've ever encountered. He could spot a good deal in a way in which many people couldn't."

Katz's father died when he was about 2. His mother worked two jobs — an RCA secretary during the day, at night typing labels for a direct-marketing company — to put food on the table of their modest Langham Avenue home in Camden.

The house was so narrow that Katz could lie in bed and touch both walls of his bedroom. He knew he was poor, but also that other kids in Camden had it worse.

He was driven even as a child, determined to perfect his basketball jump shot. He practiced on a backboard stuck to a cinder-block wall behind his house, shooting in the dark and even the cold, his hands freezing.

At 16 he entered a free-throw contest at the Jewish Community Center in Pennsauken, sinking 24 in a row to win a shiny three-foot trophy. He would recall the father-son awards banquet as one of the saddest memories of his youth, because his father was not there. On the way home that night — a neighbor accompanied Katz to the ceremony — he thought that somewhere in the universe his father was watching, feeling pride at the son's achievement.

Katz would hone his foul shot for decades, and at age 70 bested NBA star Shaquille O'Neal in a contest to benefit the Boys & Girls Club of Newark. Katz made seven out of 10 shots, O'Neal six.

From high school, Katz got a scholarship to Temple University, and worried at first that he was unequipped to compete with other students. Instead, he excelled, and later graduated first in his class from Dickinson Law School.

He loved Temple, he later told friends, because it was a place for kids who desperately wanted to learn, kids who strived. He gave $25 million to the school in 2013, which brought public acclamation, though there were many other gifts to people and organizations about which he never said a word.

Katz's stamp remains indelible on Temple, where he served as a trustee and was known for his support of student scholarships, athletics, entrepreneurship, and medicine.

Weeks before his death, when Temple announced it would name its medical school for Katz, he described how his mother had wanted him to be a doctor, but he couldn't stand the sight of blood.

"He never forgot where he came from — that's an old phrase, but Lewis lived it," said Patrick O'Connor, chairman of the Temple board of trustees. "He was proud of the fact that he was a Temple graduate, and he wanted to make Temple a place where people like him could go and get a world-class education without incurring a load of debt."

Today at Temple, "there's a big hole," O'Connor said. "There always will be."

Katz told graduates at the 127th commencement that his enormous business success was not the most important part of his life. It was his family and friends.

"Life in my view is meant to be enjoyed," he told the graduates. "It's meant to have as much fun as you can conjure up."

Katz did that, embracing his wealth and power and the freedom it brought. He delighted in the ability to go anywhere he wanted, whatever the cost, distance, or timing, be it a spur of a moment trip north to Manhattan or all the way west to Mount Rushmore.

He stayed in touch with boyhood chums while moving in circles that few could imagine, friends with Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, Barry Manilow, Whoopi Goldberg, Tom Ridge, Ed Rendell, Jay Z, Shane Victorino, Goldie Hawn, and ageless Philadelphia DJ Jerry Blavat.

He always said that whatever he did, and however much he earned, his most important job was father and grandfather. He and his late wife, Marjorie, raised two children, Melissa and Drew. His longtime companion, Nancy Phillips, is a staff writer at the Inquirer.

"Over the years, as his accomplishments grew, Lewis often spoke of wondering whether his father, or mother, or both, would take pride in his achievements," Phillips said. "In some ways, I think that propelled him. At various points along the way — the Nets, the Devils, the Yankees, the airplane, the yacht, the newspaper company — he'd stop and marvel: 'Who would have thought that a kid from Camden …' "

He also founded the Katz Foundation, which supports charitable, educational, and medical causes; helped fund a new law school building through a $15 million gift to the Dickinson School of Law at Pennsylvania State University; and gave often in Camden, among the nation's poorest cities.

There he established programs to help children, including two Boys & Girls Clubs that serve thousands of young people a year. He supported the city's Catholic schools and built Jewish Community Centers in Cherry Hill and Margate.

At his death in May 2014, Katz was a shareholder of the Nets, the New York Yankees, and the YES Network, ventures in which he pledged a share of profits to benefit inner-city kids.

Harmelin, who serves on the board of Philadelphia Media Network, said he once asked Katz: How did he do it?

"He believed that some people could play the piano, others were great ballplayers, and he was an entrepreneur," Harmelin said. "Lewis always remained aware of his good fortune. And he equally always remembered he wasn't always that fortunate, and how tough it was."

What does he miss most?

"His humanity. His humor. And his warmth," Harmelin said. "He was way too young."

Four days before his death, Katz and fellow investor H.F. "Gerry" Lenfest joined to win a climactic owners vs. owners auction for control of the Inquirer, Daily News, and Philly.com. Lenfest subsequently became sole owner and donated the media company to a nonprofit journalism institute.

At Katz's memorial service, Clinton remembered a 2007 meeting at the Clinton Foundation when, after hearing how tennis great Andre Agassi founded a school in the poorest section of Las Vegas, Katz immediately pledged to build a charter school in Camden — now the Katz Academy.

"It was just a spontaneous moment," the former president said that day. "That guy did a lot with his heart."