Temple prof co-curates first exhibit on LGBTQ video game history

Organizers have launched a crowdfunding campaign to back the exhibit's catalog. Temple media studies professor Adrienne Shaw discusses the exhibit's scope and LGBTQ representation in gaming.

In the video game Caper in the Castro, the sole playable character is on a mission. She's a lesbian detective, and it falls to her to rescue a friend — a drag queen who's been abducted in the neighborhood — and foil a plot to infect patrons at gay bars with a virus.

Those are the stakes; here's what the detective has at her disposal, or if you play it, what you have at yours: a map, a notepad, a lighter, a gun, a key, binoculars and a magnifying glass.

The game's developer, C.M. Ralph, built it on the software HyperCard, which worked on Macintosh and had its heyday in the late '80s. The game's 1989 campiness, black-and-white graphics, and floppy disks are all antiques now. Caper in the Castro is the first video game with LGBTQ themes that experts are aware of. For Temple media studies professor Adrienne Shaw, it's a favorite among the programs she's researched while tracing LGBTQ gaming history.

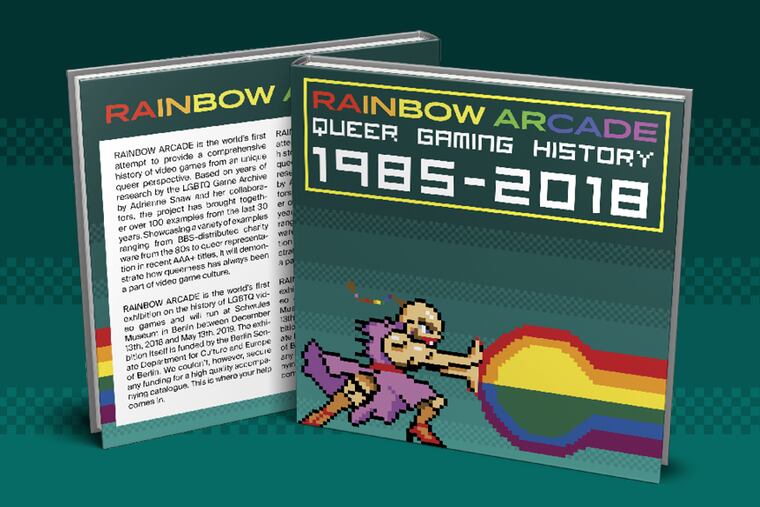

Shaw is among a team of curators behind "Rainbow Arcade," a forthcoming exhibit on LGBTQ representation in video game culture. The first-of-its-kind exhibit is scheduled to open at Berlin's Schwules Museum in December. The museum launched a Kickstarter campaign last week to back a 1,000-copy printing of the exhibit's catalog.

"It was really important for people who can't make it all the way to Berlin to make a catalog of the core content," Shaw said.

The exhibit covers more than three decades of gaming. Shaw, who founded the LGBTQ Game Archive (accessible online), noted that an example such as the Grand Theft Auto series, which has had some homophobic, stereotypical portrayals of gay characters, might feature more depictions "than even the games that are trying to represent LGBTQ people."

"Because their attempts to be edgy to a certain degree, they have more interesting LGBTQ representation than many series do," Shaw said.

The LGBTQ Game Archive points to the Marvel Universe and Super Mario Brothers, among others, for early examples of characters who may be bisexual or transgender.

"Birdo's gender identity [in Super Mario] has been the subject of much discussion," reads one entry, which later notes, "Game designer Jennifer Reitz suggests she underwent a Mario-universe version of gender confirmation surgery, while others speculate that she has to hide her identity in exported versions of the game because only Japanese consumers will accept her as a trans character." Birdo first appeared in 1988.

The exhibit will look not only at the games, but also at who plays them. LGBTQ gamer collectives sprung out of necessity, Shaw said, due to homophobia and transphobia, but also geekphobia. Gathering resources on online communities provided hurdles in the research.

"While it's fun to say once it's the internet it's there forever, it's really not," Shaw said. A niche forum that welcomed a coterie of users can disappear with a domain's expiration.

"There are a lot of early online LGBTQ gamer communities that are just gone," she said. "It's also easier to find out about Philly gay communities in the 1960s rather than Philly gay gamer communities in the 1990s because the records were digital as opposed to print."

Shaw and her colleagues turned to print sources often, especially since gaming technology has evolved so rapidly during the exhibit's 33-year span. The ability to Google "how to solve" a game is easy for current games, Shaw pointed out, but not for a game that predates the spread of the internet.

"A lot of it is relying on people to keep their stuff, which happens inconsistently," Shaw said.

Campy games are still being produced, but Shaw said that the recent decades have welcomed storytelling in video games that explore LGBTQ issues with narrative depth. In the 1990s and 2000s, Shaw said, designers and critics advocated for video games to be viewed more as an art form. This elevated ambition may have heightened the desire for gamers to see themselves reflected.

"The nuance of those story lines comes out of the idea that games are supposed to be serious — that they're not supposed to be play things, that they can communicate cultural meaning," she said. "The more games get recognized as art, the more they are taken seriously. And the more people take them seriously, the more people criticize the representation in them."

Game creation software such as RPG Maker and Twine, she continued, helped gamers tell their own stories.

"I see a much more conscious [notion of] 'Yeah, games are a place where we can expect to be represented,'" Shaw said, who forecasts more LGBTQ characters in the future. "I think that's a big change in even the last 10 years."

The exhibit's crowdfunding campaign will stay open for a month, with a goal of raising roughly $29,000 (25,000 in euros). By Monday, the campaign had raked in more than 40 percent of its goal.

Shaw said that LGBTQ representation has come "in fits and starts" over the years, which perhaps has contributed to the misconception that gay characters and topics are a novelty in video games. In the exhibit catalog, she hopes perspectives can shift from "having new content and [speaking like] it's the first time" to a better knowledge of what's existed for some time now.

"Once we know what the past is," she asked, "how can we build on it?"