Chesco victims' agency: Persistent pioneer

When the rookie state trooper first encountered a scrappy group of Chester County victim advocates in the early '80s, he wanted to tell its members: Back off!

When the rookie state trooper first encountered a scrappy group of Chester County victim advocates in the early '80s, he wanted to tell its members:

Back off!

"We typically don't embrace change well in law enforcement," Frank E. Pawlowski explains.

And the group, originally the Rape Crisis Council, certainly stood for change in the way it ministered to victims during investigations and demanded that their voices be heard at sentencings.

Decades later, Pawlowski heads the Pennsylvania State Police and credits the group, now the Crime Victims' Center of Chester County, with pioneering advances in victims' rights and "filling a huge void." The organization celebrated its 35th anniversary last month.

Among the agency's myriad services are two 24-hour crisis hotlines, one for sexual assaults and one for other crimes; companionship for victims at police interviews and court proceedings; individual and group counseling; sensitivity training; and outreach programs on topics such as date rape and bullying.

CVC has been influencing victim advocacy ever since its inception in 1973, says Carol Lavery, Pennsylvania's victim advocate. "It's an excellent model nationally," says Lavery, former head of Luzerne County's victims' rights agency.

The Chester County agency has forged regional partnerships and even attracted international attention, she says.

Groups from Japan, New Zealand and Russia have traveled to West Chester to copy its programs. Chester County was featured in a 2002 TV documentary in Japan. Three years later, the Japanese opened a sister agency named "The Margaret" after Peggy Gusz, CVC's longtime director.

In 1975, a two-day conference that CVC organized at West Chester State College attracted victim-service groups from five states and the District of Columbia, Lavery says. The conference led to the establishment of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape, which enabled advocacy groups to work together to change Pennsylvania law, according to Lavery.

Pawlowski says he came to appreciate the extent of CVC's services after he left Chester County for administrative posts in Harrisburg.

"I thought everyone did what they did," he says. "As the years go on, I hope the rest of the commonwealth will experience the same benefits."

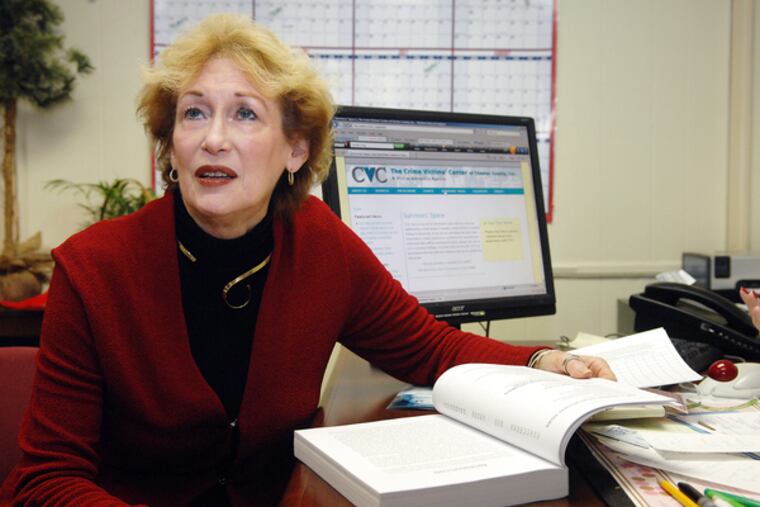

Gusz, one of the group's founding members and its second director after Constance C. Noblet retired in 1988, says she never could have imagined the agency's evolution when she and other '70s activists first mobilized.

She says they initially encountered fierce resistance from law enforcement and joked that lasting 10 years would qualify as a monumental accomplishment.

"All of the sudden they started showing up, and we were taken aback," Pawlowski recalls of the group's early years. The police reaction? "Nobody was going to tell us how to do our job."

Over time, he says, he and his colleagues realized that having advocates tend to victims' needs freed the police to focus on crime-solving.

"They were a persistent bunch," Pawlowski says. "They didn't let us box them out."

Gusz says she and her colleagues had a strategy.

"We ignored the people who wouldn't let us in," she says, "and just continued to make connections that gradually led to greater acceptance."

Throughout the years, Gusz says, victims have dictated the directions of the private, nonprofit agency, which operates with 27 employees and 22 volunteers in a three-story rowhouse stuffed with victims' mementoes. Gusz says the agency's many accomplishments are a tribute to its dedicated staff, volunteers, and board of directors.

"Everyone works so hard," she says. "You always hope that crime will disappear and you'll be put out of business."

In the meantime, Gusz says, advocates constantly search for new ways to empower victims and are always ready with tissues and a more unconventional therapy: paper clips.

Having a small piece of wire to bend gives people "something to do with their hands," which often helps them endure an emotional court proceeding, Gusz explains.

One important thing to remember in talking to a crime victim, she says, is "never say, 'I know how you feel,' because you don't."

But common themes do emerge in dealing with the aftermath of crime.

"People who have lost a loved one to homicide often agonize over the need to remember the victim without burdening others," Gusz says.

That need to reach out has led to annual candlelight vigils to honor victims' memories. One vigil generated a permanent tribute in Downingtown's Kardon Park.

Mario A. Spoto, a Downingtown chiropractor, came in contact with CVC after his sister-in-law, a 38-year-old mother, was fatally stabbed by her husband on Feb. 28, 2000 - three days before her nursing-school graduation.

After attending a CVC candlelight vigil two months later, Spoto says, he and his relatives were overcome with gratitude for the "top-quality" people who organized it.

"We saw these people with true compassion so focused on giving all these victims emotional support," Spoto says. "It was amazing."

He says he and his relatives suggested a living memorial. The agency agreed to back the project if the family solicited the funding. In 2006, Spoto, who chaired the Chester County Victims' Memorial Committee, received the Pennsylvania Governor's Victim Service Pathfinder Survivor/Activist Award for helping bring the project to fruition.

"It's a shame that we need an agency like that, but thank God they exist," Spoto says.

His wife, Cecilia, says that her sister's death hit her hard, and that she availed herself of many of the agency's offerings, including a monthly support group.

"It came to be like a lifeline," she says, adding that she now serves as a speaker for the agency.

"They were godsends," she says of the advocates. "They really deserve to have people in the community know how much they do."

Gusz, who has lived the aftershocks of horrific rapes and murders with victims - cases that can drag out for decades on appeal - says she has seen "the best and the worst" of humanity.

"Some people endure terrible ordeals with dignity and then go on to help others," she says. "But that's not to say that everyone can or should do that."

Gusz says she appreciates the numerous national and local awards that she and the agency have received.

But those aren't what keep her energized.

"Having a person say, 'I couldn't have made it through this without you,' is really what keeps us going," she says.

Aiding Victims

1973:

The Rape Crisis Council of Chester County is formed.

1975:

The council organizes a two-day forum at West Chester State College, leading to the creation of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape.

1976:

The group broadens its mission to include victims of crimes other than rape and becomes Victim/Witness Assistance Services of Chester County Inc.

1985:

The agency changes its name to the Crime Victims' Center of Chester County.

1988:

Founding director Constance C. Noblet retires; Peggy Gusz succeeds her.

1991:

Pennsylvania enacts a bill of rights for victims of crime.

1993:

Chester County establishes a policy that includes CVC advocates in the county's homicide-response protocol.

1995:

CVC provides assistance to victims of juvenile offenders.

2000:

The victims' bill of rights is amended to include victims of juvenile offenders.

2002:

CVC coordinates the formation of a county Sexual Assault Response Team to ensure respectful treatment of victims. CVC is featured in a Japanese TV documentary.

2005:

The Victims' Memorial of Chester County opens in Downingtown.

2008:

CVC celebrates its 35th anniversary.