Sculpture in Camden to honor polar explorer

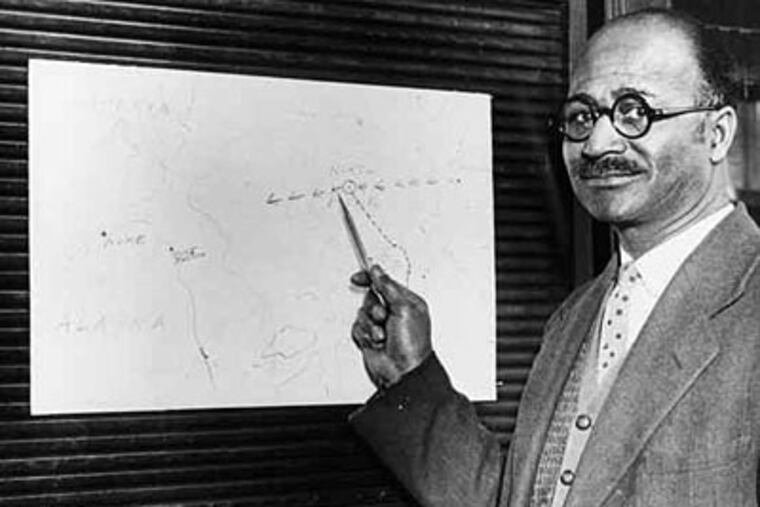

Matthew Henson was literally standing on top of the world. The bundled-up explorer had trekked more than 100 miles across the snow with expedition leader Robert Peary in 1909 and waved his hand in triumph as Peary snapped his photograph at the North Pole.

Matthew Henson was literally standing on top of the world.

The bundled-up explorer had trekked more than 100 miles across the snow with expedition leader Robert Peary in 1909 and waved his hand in triumph as Peary snapped his photograph at the North Pole.

A century later, that moment is being captured again by Haddonfield artist John Giannotti.

He is at work on a 12-foot sculpture of the African American adventurer to be installed in front of the Camden Shipyard and Maritime Museum, now under development in South Camden.

Henson's face conveys a sense of pride - and exhaustion. His right arm is raised over his head while the left arm nestles a replica of the American flag that was planted at the pole. Next to Henson is his favorite husky, King.

"This was a beautiful moment," Giannotti said this week as he finished a clay model of the onetime South Philadelphia resident and prepared to make an epoxy bronze casting.

"I've always felt you have to look for the iconic image, something that grabs the attention on many levels. I wanted it to have artistic merit, and I wanted the public to understand it."

The statue will be dedicated April 6 - the 100th anniversary of the successful North Pole expedition - at the site of the future museum, which will be dedicated to the area's maritime history.

The installation will be a milestone for the project's supporters as they plant their flag on the 1900 block of Broadway and seek financial help to open in about a year, officials said.

Henson may not be a household name, but his story drew Giannotti, whose works in the area include two Walt Whitman statues in Camden and a Hadrosaurus statue in Haddonfield.

The Maryland-born explorer wasn't credited as codiscoverer of the North Pole for decades while Peary, a Navy admiral, received many honors.

After writing one book about the expedition and collaborating on another, Henson eventually was recognized for his achievement by Congress in 1944 and by Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower. He died in 1955 at 88.

"One of the great things about being a sculptor is that you have to be a mini-expert" about your subject, said Giannotti, 63. "I got to learn about Henson. You can't do a sculpture of him without knowing him. Believe me, this gets very personal."

With associate sculptor and researcher Bill Massey, Giannotti collected photos of the adventurer from his youth to old age. "The face has a quiet strength," Massey said.

Giannotti noticed that the principal at his 12-year-old son Del's school had facial features similar to Henson's. He soon had Haddonfield Middle School administrator Noah Tennant modeling for him.

"Del actually did part of Henson," placing clay on a styrofoam human form in places "where I couldn't reach," Giannotti said. "I also had about 20 students in the middle school's art club come in to add little pieces of clay."

Some work on the statue "was planned. Some of it was gut reaction," said the sculptor, a professor emeritus at Rutgers University, where he chaired the fine arts department and founded the international-studies program.

The clay model will receive a second coat of shellac today, and tomorrow mold-maker Angelo Carolfi of Audubon will cover the statue with polyurethane. It will next be given a heavy coat of plaster.

When dry, the piece will be opened up in vertical halves. Into that mold will be laid bronze epoxy with pigments added to create hints of white, black, and various shades of bronze.

The sculpture will tell a story that began in 1887 when Peary recruited Henson at an outfitter's shop in Washington, where he worked as a clerk.

Henson was an experienced seaman, having served at age 12 as a cabin boy on a merchant ship. Over time he became a skilled navigator.

He and Peary worked at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in the late 19th century, said George Rowland, associate project director at the museum, which is being built in a former 1881 church.

The parish portion of the property is partly constructed from the stone ballast of the Kite, a sail-and-steam vessel used by Henson and Peary on their polar expedition.

The pair made many trips, including Arctic voyages that, in 1909, led Peary to include Henson in a six-member team headed to the North Pole.

During the journey, "Peary was disabled and could not walk," Rowland said. He had lost several toes to frostbite.

"So Henson went ahead, thought he found [the pole], and went back to get the boss. Who was first at the pole? Henson."

When the two returned to the United States, they had a falling out. Henson wrote a 1912 book called A Negro at the North Pole, infuriating Peary. Henson later collaborated on his 1947 biography, Dark Companion.

The statue's dedication will be attended by residents who live near the former church, Boy Scouts and others, including museum board members; Michael Lang, a Rutgers professor emeritus and driving force behind the project; and the Rev. Michael Doyle of nearby Sacred Heart Church, Rowland said.

"For me, the most important part of the sculpture is where Henson's leg touches the dog's," Giannotti said. "That means a lot when you think about what they had been through. The dog was obviously devoted to the man."