A throwback to the back, back row

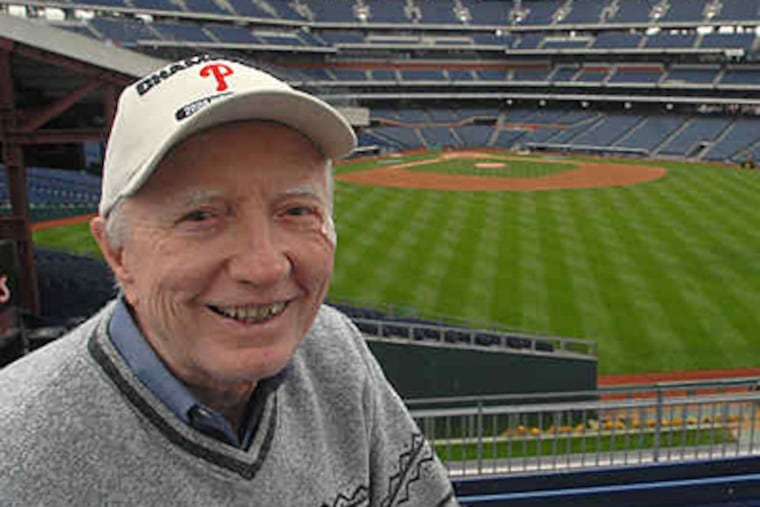

As Jack Rooney stood in empty Citizens Bank Park, silently marking the distance from his spot in the rooftop-seating section to the expanse of green below, a single thought came to mind:

As Jack Rooney stood in empty Citizens Bank Park, silently marking the distance from his spot in the rooftop-seating section to the expanse of green below, a single thought came to mind:

"We were closer," he said.

He should know. Because Rooney, 86, remembers when a Philadelphia baseball stadium had true rooftop seating - on his roof. In the 1920s, his father helped lead a group of Swampoodle neighbors who built bleachers on top of their 20th Street rowhouses and charged fans 50 cents to watch games being played across the street in Shibe Park.

Last week, as the Phillies prepared to battle the Los Angeles Dodgers for the National League pennant, Rooney made a sentimental visit to Citizens Bank Park, taking in the view from high over the outfield.

"It's still a good feeling," he said. "Reminds me of good times."

When five-year-old Citizens Bank Park was built, the Phillies reached into the city's baseball past for one particular design element. Atop a row of food concessions, the team installed a bleachers section that mimics the height and location of the rooftop stands near long-gone Shibe Park.

Of course, the 199 bleacher seats at Citizens Bank Park cost more than 50 cents. But they are among the least-expensive in the ballpark, $16 and $18, available to groups and organizations.

Venerable Shibe Park stood at 21st and Lehigh, its 12-foot right-field wall parallel with 20th Street.

From almost the day the home of the Philadelphia Athletics opened in 1909, people used the flat roofs of their rowhouses as viewing platforms, setting out chairs and ice buckets. That free, expansive view of the game brought enormous joy and, eventually, enduring enmity between the neighbors and the team.

Today, Rooney is an emeritus professor and director of the master's program in clinical psychology at La Salle University. He's a coauthor of a new book designed to help students prepare for college and, of course, a lifelong baseball fan.

He was 2 when his family moved into 2739 N. 20th St. in 1925.

A few years later, he recalled, his father said to him: "Come here, Jack. There's something I want you to see. You can remember all your life."

His dad took him up the stairs to the second-floor bathroom, where a ladder lay against the rim of the open skylight. His father helped him up and onto the roof, where young Rooney beheld a glorious sight: the whole of Shibe Park.

As the boy looked onto the field - the grass the greenest green - he saw not just the stadium, but an Athletics outfield composed of three all-time greats: Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Al Simmons.

Shibe Park was the major leagues' first steel-and-concrete stadium, named for Ben Shibe, who with Connie Mack owned the Athletics. The Phillies played five blocks away at the Baker Bowl.

The ballpark was part of the reason Rooney's family settled on 20th Street. His father loved baseball, and played semipro games on local fields, often earning more money on a weekend than he did during the week at a plumbing-supply business.

Rooney's mother didn't like the house. She would have preferred a nicer neighborhood, away from the noise and commotion of the ballpark. But she was outvoted, 3-1, by her husband and sons, Jack and his younger brother, Gerry.

Rooney and his dad saw not just the game's beauty, but also its financial opportunity. The rooftop stands were packed. The father even built an outside stairway so fans could more easily reach the roof. Young Rooney made money selling lemonade, peanuts, hot dogs, and newspapers.

"Throughout the baseball season," he said, "we were entrepreneurs."

At the time, team owners wouldn't let newsreel crews into the park. They thought people wouldn't buy tickets if they knew they could later see film of the game in a movie theater. The Rooneys welcomed the news crews onto their roof - for $20.

"I learned very early as a kid that baseball is a business," Rooney said.

For instance, he was a student at St. Columba School when the A's played the Chicago Cubs in the 1929 World Series. A nun asked the class who wanted the A's to win.

Every hand shot up. Except Rooney's.

"If Chicago wins today, we go another game," he told the nun. "We make more money."

As it went, the A's won the Series in five games. And to Rooney, baseball wasn't just business. It was excitement and bustle and fun, game day defined by the crowds and the characters.

One street corner was the well-defended domain of a one-armed peanut vendor, always nattily dressed, Rooney recalled. A former ballplayer who had suffered a head injury would idly roam the block, every so often shouting out, "Bingo!"

Shibe Park stayed busy. It held exhibitions of donkey baseball, in which batters had to hit the ball, then coax a reluctant donkey to ferry them around the bases. Boxing matches and football games drew thousands. Once the park held a motor competition among "women drivers," then a rare breed.

"I don't think of it just in terms of baseball," Rooney said. "A lot of people who grew up in Philadelphia neighborhoods, there was a certain camaraderie. People helped one another out and knew one another."

Though Rooney loved the A's, "I didn't have any interest in getting into the park." He preferred to sit on his roof.

But things were about to change.

In 1935, upset that fans were seeing the game without buying tickets, the team set out to block the view. The A's installed a 22-foot, corrugated metal barrier on top of the right-field wall.

Fans immediately gave the obstacle a name: the Spite Fence.

The fence may have forced some fans to buy tickets, but it cost the A's something more dear than money, separating the team from the neighborhood. People who were crazy for the A's felt unwanted.

"It wasn't the same," Rooney said.

The A's fortunes slipped with the Depression. The Phillies, eager to cut expenses, arrived as a cotenant in the middle of the 1938 season.

When war came, Rooney joined the Navy, his brother the Army. The vote at home was no longer 3-1. His mother got her wish, and the family moved to Lawndale in 1945.

The A's, too, would move, leaving for Kansas City, Mo., after the 1954 season. Shibe Park was renamed Connie Mack Stadium in 1953, and closed in 1970.

Today a church stands at 21st and Lehigh. Shibe Park exists only in photographs and memories, and in the echoed placement of certain seats at Citizens Bank Park.

"Looking at it now, with no one here," Rooney said last week at the ballpark, "that's how my mother liked it."

Because when the stadium was quiet and still, he said, it let her take in the whole of the beautiful outfield grass. It reminded her of a park across the way from her girlhood home, a place she loved when she was young.