Camden alternative school seeks financial help

It was born of necessity at a beauty salon after high school students complained of a particularly bloody week in Camden's schools, some of New Jersey's most dangerous.

It was born of necessity at a beauty salon after high school students complained of a particularly bloody week in Camden's schools, some of New Jersey's most dangerous.

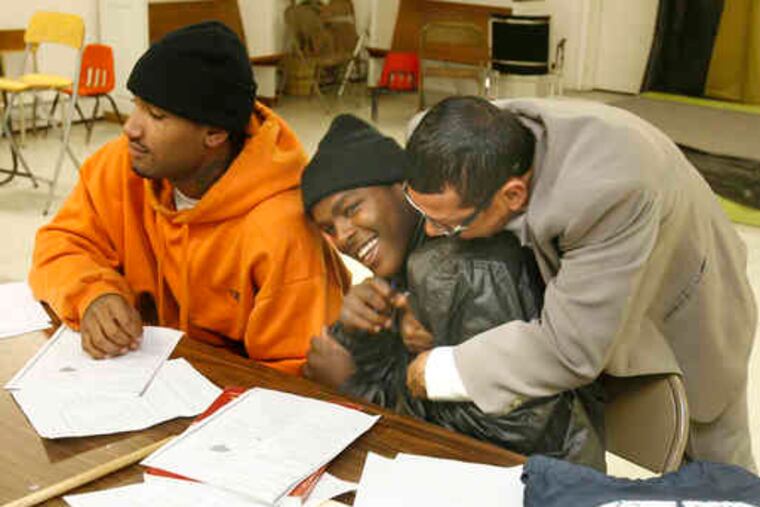

With little educational experience and few resources, an African American preacher and a Latino activist created an alternative high school that attracted students by the dozens: Bloods and Crips, middle school dropouts and barely literate adults, African Americans and Latinos.

Three years later, the school, housed in an East Camden church, has hundreds of students, most of whom go through a five-month, mornings-only crash course in math, science, English, civics, and history. They then go on to trade schools, the military, and even Camden County College.

Unusual in its inception and structure, with $100-a-week teachers working without state credentials and diplomas issued without state recognition, the school was given new legitimacy this year when Gov.-elect Christopher J. Christie spoke there twice while running for office - at a graduation and at an orientation.

But this little experiment in urban education is at death's door, leaders say. They say Bethel United Methodist Church, which has underwritten the school's utility bills despite its own shrinking membership, has said it is in debt and will soon turn the electricity off.

"It's just to the point that unless something happens soon, we're going to have to declare this is impossible to do anymore," said the Rev. Tim Merrill, a teacher and the school's cofounder.

"The rough part is, this actually works. Kids are getting smarter. Kids are buying into education."

The school opened quickly, just weeks after a meeting at a beauty salon across from Woodrow Wilson High School with parents of beaten students. Because of the need for a safe haven, Merrill said, there was no time to raise start-up money, and the school has never been financially secure.

News of the imminent utility shutoff has put the school in an even more precarious situation, he said. Plus, the school had its third break-in this week: Vandals made off with an air-conditioning unit and speakers while destroying the alarm system.

Two church houses two programs. The first, the Community Educational Resource Network, has more than 300 students, with some picking up homework but not attending classes. All must read five books, write several essays, and pass two weeks of finals.

Graduates, from ages 18 to the 50s, get a "home-school diploma." Even without a sanctioned degree, they can go on to graduate from some programs at Camden County College. More than 800 have graduated.

"There's a lot of education going on," cofounder Angel Cordero said. "But more than that, there's stabilization. We have to stabilize these kids, get them to get along, dress better, stop saying the F word."

The second program, four-year East Side Prep, consists of 16 students on track to get a private Christian school degree and possibly go to a four-year college.

"People come here because they're trying not to get into trouble. They're trying to learn things," said student Michael Duran, 17, who was repeatedly suspended at Wilson.

Students describe the program as a last chance. Many have dropped out of or been expelled from public schools. Others say they have been beaten up so often they refuse to return.

"I couldn't learn," said Ray Rivera, who dropped out of Camden High School. "It was a war zone more than anything else. Thank God I came here."

Rivera is now getting a degree in criminal justice at ITT Tech, and he helps out at the program in his free time.

Students say racial tension and violence do not exist at the church. That's because, according to Cordero, only students who say they want to learn - rather than those assigned by a judge, for example - are admitted.

Program graduate Traina Heredia got a certificate in computerized accounting technology from Harris School of Business this week. At the church, she said, the one-on-one attention made all the difference.

She described the program as harder than public school, where her favorite class was gym. At the church, she learned to love math, and she now hopes to be an accountant. If she had stayed in public school, she said, "I probably would've been locked up."

Some new students can't find New Jersey on a map and don't know what July Fourth is, one teacher said. So basic history and writing are stressed.

This week, students had 15 minutes to write an essay beginning with this sentence: "Santa Claus was apprehended by authorities at 2:37 a.m. on Christmas Eve."

Teachers hustle for educational materials. The History Channel's Web site is used as a resource for a class on presidents, while Berlin Township's Townsend Press, an educational publisher, donated the textbooks and paid for a teacher's salary.

But Merrill said he was frustrated that there had not been more support from churches or educational groups.

"I wasn't looking to be a high school educator. I was a seminarian trying to get a couple more degrees," he said. "So if there are some organizations out there that do this, we invite them to come in and look at this. Buy us out for no money."

The regional United Methodist Church superintendent, the Rev. Vivian L. Rodeffer, said the program was not affiliated with Bethel United Methodist. But she said she was trying to get emergency funding for the program or a new church location.

"I'm concerned because it's such a wonderful program, I don't want it to end," she said.

Merrill believes that some are scared to get involved with the population he is targeting, he said.

"Kids come in sometimes and smell more like weed than Right Guard," he said. "The only way we're going to get to the core of what ails Camden is to get to those that represent a risky proposition."