'Fear factor' described in kids-for-cash case

Panel heard of Luzerne County judges' reign of power.

WILKES-BARRE - They were known as "Scooch" and "the Boss," and together they unleashed a five-year reign of terror over Luzerne County's courthouse and schools.

"Scooch" is the nickname since childhood of former Judge Mark A. Ciavarella Jr., whose real name came to strike fear into any child unfortunate enough to come before him, even for relatively minor infractions, such as writing on stop signs with a felt pen.

The word in high school classrooms and halls was: If you go before Judge Ciavarella, you're likely to go to jail - especially if he's in a bad mood over Penn State's losing a football game.

"The Boss" was Michael T. Conahan, who was a glowering, unsmiling presence in the century-old courthouse, where intimidation seemed to whistle out of the duct work and swarm over the room like angry bees. Conahan kept a full-nelson grip on the courthouse staff by populating it with his cronies and relatives. Even to Judge Ciavarella, Judge Conahan was the Boss.

These characterizations and accounts have emerged from testimony before a special hearing over four days and two evenings here. A commission is working to determine how former Judges Ciavarella and Conahan could have conspired over five years to deprive thousands of children of their most basic constitutional rights and send them off in shackles to detention centers in which the judges had personal financial interests.

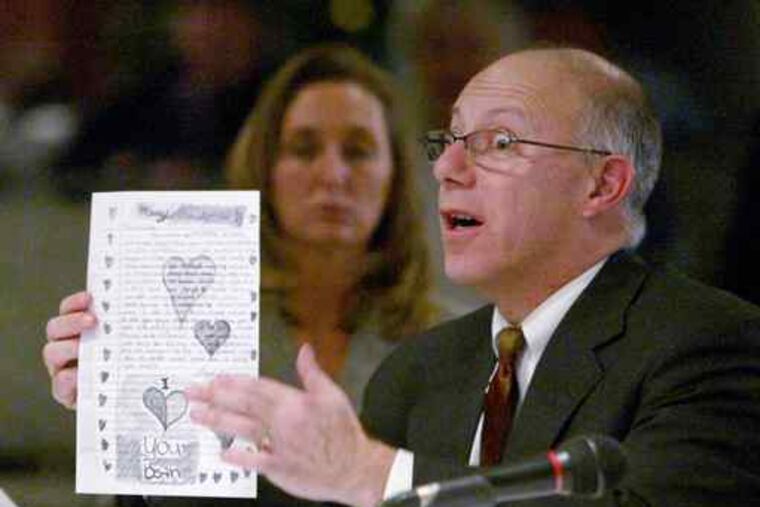

"There are many reasons that this tragedy occurred, but intimidation was clearly one of them," said Superior Court Judge John M. Cleland, chairman of the 11-member Intergovernmental Commission on Juvenile Justice. "Part of this fear factor was greed and ambition on the part of court personnel. You didn't get ahead in Luzerne County by making trouble for the people in power."

Conahan and Ciavarella are charged with 48 counts of racketeering and related charges for allegedly taking $2.8 million in payments from the builder and former co-owner of two private juvenile detention facilities. They originally entered conditional guilty pleas in the case, but withdrew them when a federal judge rejected the terms of their plea agreement. Prosecutors responded with a broadened indictment. The two former jurists have denied the charges.

During the commission hearings, witnesses told of unyielding pressure from Conahan and Ciavarella that led to questionable practices going unquestioned and becoming accepted practices:

In violation of state law, Ciavarella set up tables outside his courtroom where teenage defendants were persuaded to sign forms he created that waived their right to counsel. Once inside his courtroom, Ciavarella, contrary to state law, did not advise his young, unrepresented defendants of the consequences of waiving counsel or of pleading guilty.

Even before being declared delinquent, juveniles were sent to detention centers for as long as two weeks to await psychological evaluations. They would eventually be examined by the court-appointed psychologist, Frank Vita, Conahan's brother-in-law. Vita's recommendations were nearly always the same - "placement," meaning jail.

Hearings before Conahan, which often lasted only a few minutes, were typically interrupted by conversations about college and professional football games and NASCAR racing between the judge and arresting officers and other court personnel. Ciavarella also used the opportunity to collect and pay bets made on games.

Ciavarella established a special "fines court" that would send children to detention centers until their parents could pay for fines imposed by district judges. In one case cited at the hearings, an 11-year-old boy was taken away when his parents were unable to pay a $488 fine. Although the child was only 4-foot-2 and 63 pounds, Ciavarella had him handcuffed and placed in leg shackles.

Conahan's aura of power was enhanced by his longtime association with reputed organized crime figures in Northeast Pennsylvania. Federal court testimony this year said he and William "Big Billy" D'Elia met regularly at a favorite booth in a local restaurant.

D'Elia, reputed leader of one of the nation's oldest organized crime families, is serving nine years in federal prison on money-laundering and witness-tampering charges.

"Politicians and organized crime have been married up here for a long time," said William Kashatus, a local historian who has written five books about the anthracite region. "Conahan's association with D'Elia was well known, and it only added to the mystique that made people afraid of him."

A graphic insight into Conahan's methods was provided at the commission hearings last week by Maryanne C. Petrilla, a Luzerne County commissioner who said the former judge vehemently opposed her decision to fire Sam Guesto as county manager. She said Conahan initially had about 40 local political figures telephone and ask her to change her decision. When she declined, she said, she received a personal call from Conahan.

"The conversation was not what I would call a friendly phone call," Petrilla testified. "He said I could not replace Mr. Guesto. And I said, because of everything that is unfolding, I felt it was important for the county to go in a new direction. And his final words to me were, 'Maryanne, if you do this, you will be finished.' "

Petrilla did not relent and is still a commissioner. Guesto resigned but then was given a job in court administration by Ciavarella.

Petrilla also told the commission that the levels of cronyism and nepotism in the court system were "extremely high," and this was one reason that no one in the courthouse challenged the treatment of juvenile defendants. "The courts hired family and friends, and as a result of the hiring of family and friends, those people who may have seen wrongdoing remained silent," she said.

Commission members were frequently frustrated in their attempts to determine how so many individuals could have stayed silent for so long about what one advocacy group, the Philadelphia-based Juvenile Law Center calls "one of the largest and most serious violations of children's rights in the history of the American legal system."

Cleland posed the question to David W. Lupas, who was the district attorney when many of the abuses occurred, after he testified that none of his assistants ever brought concerns about Ciavarella's conduct to his attention.

"Your testimony was that you never heard it discussed among any of your assistant D.A.s, defense lawyers, public defenders, or anyone involved in the system. Now, either there was incredible incompetence, which I find it hard to believe among that many lawyers and professionals, or there was an awful lot of intimidation about reporting and discussing what was going on. Which was it?"

"I can only surmise that the judge was the judge," Lupas said. "The judge was in charge. The judge handed down kind of his policies, and everyone followed those policies."

The former juvenile probation chief answered the same question this way: "When a judge asked you to do something, you did it."