Preventing duck boat crash would not have taken much

Ten feet. Had Matthew R. Devlin walked that far, he could have alerted his tugboat captain that he was experiencing a family emergency, in all likelihood saving the lives of two Hungarian tourists who died in the July 2010 duck-boat accident.

Ten feet.

Had Matthew R. Devlin walked that far, he could have alerted his tugboat captain that he was experiencing a family emergency, in all likelihood saving the lives of two Hungarian tourists who died in the July 2010 duck-boat accident.

One minute.

Had Devlin, the first mate, kept watch as the tug pushed a 250-foot barge down the Delaware River, that is all the time he would have needed to turn his boat to avoid the collision that killed Dora Schwendtner, 16, and Szabolcs Prem, 20.

Two lives were lost because of failures both small and epic that day, leading to a $17 million settlement Wednesday for the families and 18 surviving passengers when the federal lawsuit suddenly ended after less than two days of testimony.

The families of Schwendtner and Prem, who will receive $15 million of the total, told reporters before the settlement that nothing could replace their children.

"We have no holidays anymore," Mari Prem said Tuesday outside the federal courthouse at Sixth and Market Streets. "Since our children have died, there is nothing to celebrate."

The families said they wanted to learn the truth about what happened. More pieces of the truth emerged during testimony Monday and Tuesday and in depositions that became part of the public record last week.

While the case seemed to settle abruptly after U.S. Judge Thomas O'Neill Jr. urged the parties to try talking again, lawyers familiar with such cases say that is not unusual once a trial begins.

The courtroom can serve as a kind of crucible. Families of victims are often present. Witnesses often fumble on the stand.

"Oftentimes cases are not settled until the defendants see the whites of the eyes of a jury, or in this case, of a federal judge who is about to decide the issue," said Tom Kline, a veteran plaintiffs' lawyer whose firm represented two duck-boat passengers.

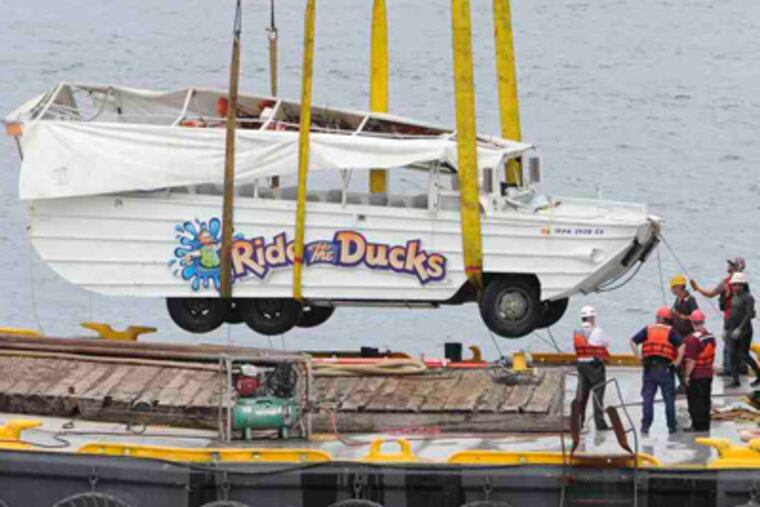

Last June, lawyers met to try to settle the case. In attendance were attorneys for Schwendtner, Prem, and the other passengers; for Ride the Ducks, which operates the amphibious vehicles; and for K-Sea Transportation Partners, which owned the tug and employed Devlin.

Robert Mongeluzzi, the lawyer for Schwendtner and Prem, had initially asked for $50 million to settle. But when the parties met again in June, he said he would agree to $24 million; the companies countered with $5 million. They weren't close, so they headed to trial.

On Monday morning, squadrons of well-dressed lawyers settled into O'Neill's courtroom. About 24 were involved in the case, though not all appeared in person.

Lawyers for K-Sea and Ride the Ducks argued that only one person — Devlin — was responsible for the accident.

Panicked after learning that his 5-year-old son had been deprived of oxygen for eight minutes during what was supposed to be routine surgery, Devlin was on his cellphone talking to family members instead of maintaining a lookout on the Delaware. His inattention caused the barge to crash into the duck, whose captain had stopped on the Delaware because he thought the boat's engine was on fire.

It turned out that Devlin's son was fine. But as he frantically sought information about what was happening, he "lost his faculties," K-Sea lawyer Wayne Meehan said in court.

Mongeluzzi said he would present evidence showing that the accident did not happen simply because a terrified father made bad choices. K-Sea executives, Mongeluzzi argued, knew that their employees regularly ignored a policy forbidding personal cellphone use on watch.

"This accident was the by-product of years of ineffective and inconsistent policy by K-Sea," Mongeluzzi said in his opening statement.

Ironically, duck-boat deckhand Kyle Burkhardt's father once worked for both Ride the Ducks and K-Sea.

In his deposition, the younger Burkhardt said his father often complained to K-Sea management about a deckhand on his boat "who was constantly on his cellphone."

"They said they would always take care of it," Burkhardt said. "But I don't know if anything was ever done."

Devlin, who is serving a one-year prison sentence for the maritime equivalent of involuntary manslaughter, said in his deposition that he often talked on his cell at work.

"You weren't some rogue employee who was using your personal cellphone while on watch while no one else did it. ... In fact, you were doing what everybody else did, right?" Mongeluzzi asked Devlin.

"Yes," Devlin replied.

He also testified that hearing about his son had caused him to stop thinking clearly.

His deposition makes painfully clear how little it would have taken to prevent the accident. Devlin knew that K-Sea's policy was to alert another crew member if he was experiencing a problem.

"How far away was the captain's cabin from where you were," Meehan asked.

"Ten feet," Devlin responded.

"Could you have easily called the captain?" Meehan continued.

"If I was thinking clearly, yes," Devlin said.

On Monday and Tuesday, duck-boat passengers Alysia Petchulat and Kevin Grace took the witness stand, painting a clear picture of the terror of that day. They were visiting from Illinois with their children and feared they would die when the barge hit their duck boat, plunging it under the water.

"The river just rose up and swallowed us," Grace said. "We didn't even have time to take a breath."

The other witness who testified in the courtroom, Luis Fernandes, a deckhand on the tug, repeatedly changed his answers under intense question from Mongeluzzi, damaging his employer's credibility.

After first saying he was only required to make "safety rounds," checking on Devlin or whomever was keeping watch every two hours, Fernandes admitted he should have done the checks hourly.

Mongeluzzi also argued that evidence showed repeated failures by Ride the Ducks. The company's air horn, which could have sounded a warning to Devlin, did not work because Capt. Fox had turned off the engine.

Fox also did not tell passengers to don life jackets until moments before the collision, even though the duck had been stranded on the water for about 12 minutes.

In his deposition, Fox said he did not believe his passengers were imperiled until moments before the barge hit. He feared that passengers would become uncomfortable or sick if they put on life vests.

"I didn't need anybody passing out or having anybody having heatstroke or any related heat issues," Fox said.

The U.S. Coast Guard suspended Fox's maritime license for five months because he did not ask passengers to don life jackets and because he failed to call the Coast Guard when the duck boat was stranded.

Schwendtner's parents, Aniko and Peter, and Prem's mother and father, Mari and Sandor, returned to Hungary on Wednesday.

On Friday, their lawyers sent a letter to Mayor Nutter, asking that the city prevent the duck boats from traveling on the Delaware. They also want Philadelphia to place a bench memorializing their children at Penn's Landing.

Nutter's spokesman, Mark McDonald, said the mayor is considering the request.

Contact Miriam Hill at 215-854-5520, hillmb@phillynews.com or @miriamhill on Twitter.