A new, unusual twist in death-penalty fight

When condemned fugitive Joseph Kindler was returned to Philadelphia in 1991 after two escapes, three years on the lam in Canada and four fighting extradition, the news was grim.

When condemned fugitive Joseph Kindler was returned to Philadelphia in 1991 after two escapes, three years on the lam in Canada and four fighting extradition, the news was grim.

Prosecutors argued - and Pennsylvania judges agreed - that by fleeing, Kindler had forfeited his rights to appeal his death sentence for the 1982 beating and drowning of a witness against him in a burglary case.

Kindler's lawyers fought that issue to the U.S. Supreme Court and back until 2011, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ordered that Kindler get a new death-penalty hearing or be sentenced to life in prison.

Now 54, Kindler is again before a Philadelphia judge, fighting for his life on an unusual legal theory: He cannot fairly be executed because in the 32 years since the slaying of 18-year-old David Bernstein, witnesses and mitigating evidence that might persuade a jury to spare his life have died or been destroyed.

At a hearing Wednesday before Common Pleas Court Judge Benjamin Lerner, Assistant District Attorney Mark Gilson said the only person responsible for Kindler's plight is Kindler, who ran the clock as a fugitive and in multiple appeals.

"It's like the guy who kills his parents and then asks the judge for mercy because he's an orphan," Gilson said after the hearing. Gilson argues that Kindler should get his new hearing over with and go back on death row.

Kindler's current lawyer, Andrea Konow, of the death-penalty unit of the Defender Association of Philadelphia, urged Lerner to bar another death-penalty hearing and sentence Kindler to life.

Regardless of the reasons for Kindler's tortuous legal history, Konow said, under current legal standards it is impossible for her to present a constitutionally valid defense in a death-penalty hearing.

Long before "don't snitch" became a staple of street culture, there was David Bernstein.

In April 1982, police raided Kindler's apartment on Ridgeway Street in the Northeast and found more than $100,000 of electronics equipment, jewelry, art, and television sets, much of it taken from an electronics-equipment warehouse in Lower Moreland Township in Montgomery County.

Police arrested Kindler, then 22, and Bernstein and charged them with being part of a burglary ring targeting Northeast Philadelphia, Abington, and Lower Moreland Townships.

Both were free on bail awaiting trial when Bernstein decided to become a prosecution witness.

He was granted immunity and on July 26, 1982, was to testify against Kindler in a Montgomery County Court trial in Norristown.

He never made it. Instead, Bernstein's body was found that night in the Delaware River off Bensalem, Bucks County. The autopsy showed that he had been hit in the head with a baseball bat more than 20 times but was alive when he was tossed into the river with a chunk of concrete block tied around his neck.

Though Kindler had accomplices and went to trial with a 17-year-old friend, only Kindler was sentenced to death after the prosecutor argued that he was the one who planned Bernstein's slaying.

Kindler's lawyers appealed, and 10 months later, Kindler was in the Philadelphia Detention Center when he and Reginald Lewis, another convicted murderer, escaped.

On Sept. 19, 1983, Lewis and Kindler sawed through the external bars of a cell in an escape Lewis later said was planned with the help of several guards and funded by a prison drug ring.

Lewis was arrested in Buffalo. Kindler kept heading north.

About seven months later, Canadian police arrested Kindler, who was living in a resort area 40 miles north of Montreal, on burglary charges.

His extradition to the United States, however, was stalled when Canadian authorities balked because he would face the death penalty in the murder case. In January 1986, Canadian officials reversed themselves, citing a fear that Canada could become a haven for fugitive U.S. murderers because it had abolished capital punishment.

Kindler's lawyer appealed, but Kindler didn't wait for a decision. In October 1986, he escaped again. This time, his fellow inmates hoisted him to the roof through a skylight and he rappelled down the walls using a rope made of bed sheets.

Kindler's second escape bought him two more years of freedom that ended Sept. 6, 1988, when he was arrested in St. John, New Brunswick, after being recognized from an episode of the America's Most Wanted television show.

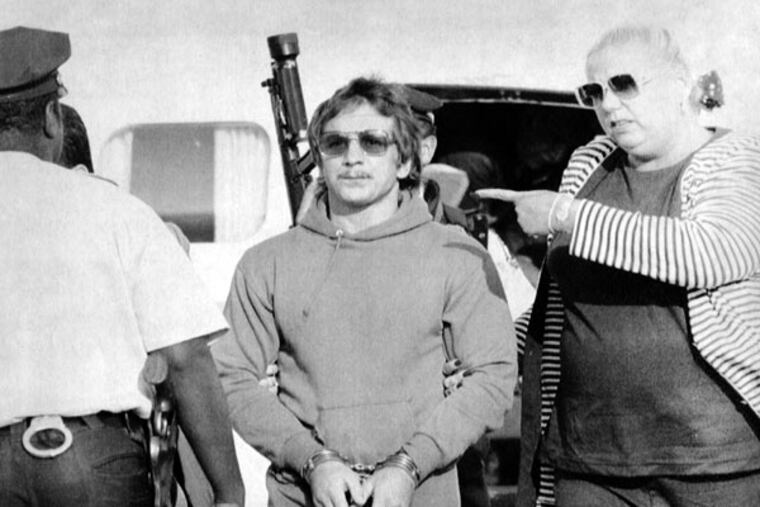

Kindler again fought extradition but was returned to Pennsylvania on Sept. 16, 1991.

At the airport were Morton and Beatrice Bernstein - David's parents.

"We've been waiting for this day for 10 years," Morton Bernstein told a reporter.

They died waiting - Morton in 2005 at age 82, Beatrice in 2008 at 82. Gilson said David Bernstein's brother is alive and could testify.

Joseph Kindler was sentenced to death at a time when the concept of mitigation - mining a defendant's personal and psychological history for a compelling reason for a jury to opt for life in prison instead of lethal injection - was relatively new.

New or not, the Third Circuit ruled that Kindler's rights were violated because his 1983 trial attorney failed to present mitigation evidence.

And, says Konow, the mitigation evidence might have persuaded a jury to spare Kindler's life.

Testifying Wednesday, Cassandra Belter, a mitigation specialist with the Defender Association, said Kindler's childhood was marked by domestic violence that began in utero.

Joseph Kindler Sr. and his wife, Magda Koltay, were Hungarian immigrants who fled to Philadelphia in 1956 during the unsuccessful Hungarian Revolution. Magda was 13 when she arrived and 17 when she became pregnant with Joseph Jr.

Belter said Kindler's mother abused alcohol while she was pregnant and was "sliced" by her husband during a fight. His mother was also hospitalized during the pregnancy with swelling in her legs and kidney problems.

As a child, Kindler was reportedly plagued by chronic high fevers and had two accidents in which he may have sustained brain damage, Belter said.

The problem, she told Lerner, is that medical records from Kindler's birth, childhood, and later hospitalizations are so old they have been destroyed.

Kindler's parents divorced but are alive: Joseph Sr., 81, still lives in Northeast Philadelphia, and Koltay, 72, lives in Illinois. Kindler's sister, Magda, 50, is in Vermont.

Belter said Kindler's parents' memories are now fragile and conflicting. Without medical records and other documents to corroborate their memories of their son's childhood, the case for mitigation is shaky, Belter said.

"Jurors always want to know what a person was like at the time of the offense, what were the things that shaped him," testified Russell Stetler, an Oakland, Calif.-based lawyer and expert on mitigation evidence in capital cases.

"What troubles me about this case is not just the harm to Mr. Kindler lacking this evidence to present, but it also puts a lot of pressure on the decision-makers - the jurors," Stetler added.

The hearing continues before Judge Lerner on Dec. 4.

jslobodzian@phillynews.com 215-854-2985 @joeslobo