Spill threatens Big Easy

Five years after Katrina, the man-made disaster could crush its economy.

NEW ORLEANS - With the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina approaching this summer, New Orleanians had just begun to breathe a sigh of relief from the storm that devastated their city and region.

The "City That Care Forgot" has shown increasing signs of revival. Its football team won this year's Super Bowl; a popular HBO series, Treme, about musicians in the city, has taken off; and a new mayor was sworn in. The Big Easy has regained some of its insouciance.

But now another disaster is at hand, possibly more economically harmful than Katrina. The Gulf of Mexico oil leak, the biggest in U.S. history, has killed 11 rig workers, closed beaches and fishing waters, killed hundreds of fish and fowl, and threatened the region's seafood and oil industries. Some area notables, such as Democratic consultant James Carville, dub it a "slow-motion Katrina."

Potentially worse, last week marked the beginning of hurricane season, with experts predicting it could be the most active one since 2005 - the year Katrina hit.

A hurricane, experts say, would be a worst-case scenario. The high tide and winds would wash the black tide ashore and into places no one imagined it would go. Already the oil slick has begun to infiltrate Louisiana's precious estuaries, wetlands, and marshes, which help to buffer the New Orleans area from hurricanes and serve as the spawning grounds for the area's thriving seafood industry.

The New Orleans area is vital to the U.S. oil industry; it accounts for 30 percent of U.S. oil production, with more than 3,500 oil rigs, and provides thousands of jobs.

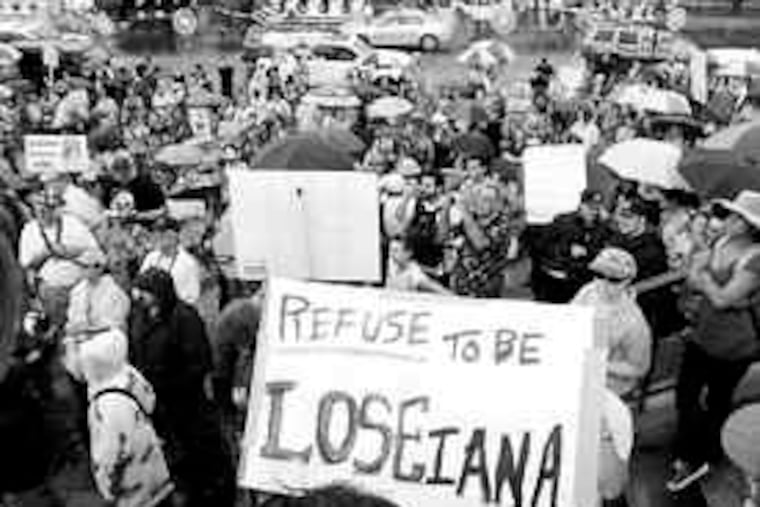

Some local leaders are becoming "squeaky hinges," saying the spill is beginning to eclipse Katrina. It is surely the worst man-made disaster in U.S. history, they argue, and, like Katrina, destroying lives and livelihoods.

"Businesses and restaurants here were already in the throes of Katrina, laden with bank loans trying to rebuild," New Orleans lawyer Bernard Charbonnet said as he made the rounds of news shows warning of the dangers.

So fearful have local hotel owners become of harm to the tourist industry that a group of major hotel owners has filed a lawsuit against BP P.L.C., in anticipation of their losses. Plaintiffs include the Bourbon Orleans, Astor Crowne Plaza, and Marriott Convention Center.

"These hotel owners are already beginning to experience how the oil spill and the resulting contamination has an adverse effect on our local tourism and business travel - an industry that is vital to our state's economy," said Stephen Herman, attorney for the hotels that sued.

A group of Gulf Coast restaurants also sued BP, citing a decline in customers and increases in seafood prices.

"I'd rather have a hurricane any day than this," said Merlin Schaefer, an owner of Schaefer & Rusich Seafood in the city's Bucktown section, who already had to lay off two of six employees because of higher seafood costs. He has had to buy a new truck to make regular runs to Texas, Lake Charles, and other locations to procure shrimp, and crabs are unavailable.

New Orleans so far has been insulated from the worst effects by its inland location, 50 miles from the hardest-affected areas of Grand Isle and Fourchon.

For city residents like Laura Battles, 31, the brunt of the crisis has not been fully felt. But her husband is a Shell Oil executive, and she was worried.

After unloading her baby, Alexandria, and toddler, Fiona, from a cross-river ferry the other day, she confessed that her husband was concerned about the prospect of laying off hundreds of workers because of a moratorium on new drilling.

"All the jobs are going to go to the Middle East," she said as Zydeco music filtered through the air from speakers near the Riverwalk Marketplace mall. "Even so, I think they're overstating this Katrina thing. It's bad, but people say 'Katrina' for everything bad these days. . . . It's a slow creep. For instance, we didn't go to the beach this Memorial Day because of the tar."

Henry P. Julien Jr., an lawyer visiting a Cafe Du Monde at Riverwalk, had a similarly mixed reaction. "Clearly it's not Katrina," he said, as a window offered a tableau of huge oil tankers and tugs gliding on the water. "There aren't 2,000 people dead and a million people evacuated. It's not worse by a long shot."

But "it's going to mean a significant economic loss," Julien said.

Michael Fridge, who operates a city tour agency, Cajun Encounters, was bracing for the effect of the spill, but he said he had not felt it yet "except the price of oysters going up."

As if to emphasize the importance of seafood, two giant red lobsters with mandibles extended stood in front of a seafood restaurant just outside Riverwalk. This was Poppy's "Crazy Lobster - Home of the Steamed Seafood Bucket" - one of the restaurants that depend on the class of seafood produced in the marshes, wetlands, and estuaries of Louisiana.

Inside, Juan Nieves, assistant director of operations, was unconcerned. "A lot of business conventions are still coming down," he said. "We're doing well."

But, he said, "I think the first impact we'll see will be from people who become afraid to come because of concerns about the safety of the food."

Nieves confided an ace in the hole for the restaurant: "We get a lot of our lobsters from Maine, and a lot of our crabs come from Alaska."

Back near the Riverwalk, a ticket-kiosk operator for the Creole Queen ducked in and out of the kiosk to snap pictures for tourists in front of the riverboat.

"It's not yet Katrina. But it's going to be," said the woman, who sported rhinestone fleur-de-lis and would give only her first name, Pam. "It's a dominoes effect. The hotels are already complaining. Grand Isle is completely shut down."

She of all people, she said, ought to know about comparisons to Katrina.

"Katrina took my house. I live in Mississippi now," she said. "I can't take no more of this."