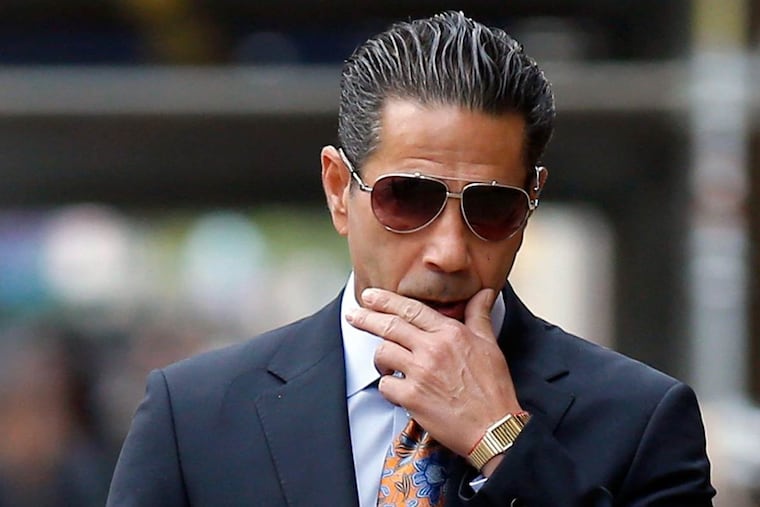

On trial again, Joey Merlino claims he's left the mob behind

But this week, reputed Philadelphia mob boss "Skinny Joey" Merlino, 55, once again will find himself in a federal courtroom - fighting a case that could force him to grow old in prison.

He's survived more than a dozen attempts on his life. He's dodged murder raps of his own. He's won and lost battles with the feds — and tried in recent years to refashion himself as a retired man of leisure and Florida restaurateur.

But this week, reputed Philadelphia mob boss Joseph "Skinny Joey" Merlino, 55, once again will find himself in a federal courtroom — fighting a case that could force him to grow old in prison.

The charges, unveiled by prosecutors in 2016, are all crimes that Merlino has faced and fought before – racketeering, conspiracy, illegal gambling – with one significant exception. In a first, investigators allege that Merlino led a Mafia attempt to muscle into health-care fraud with a racket involving prescriptions for topical pain creams.

Still, as jury selection is set to begin Monday in Manhattan, Philly's own mouthy celebrity mobster appears to like his odds.

Merlino reportedly rejected a plea offer last summer that carried less than two years in prison in a case that could put him away for 20.

The trial, which will play out over the next month in New York, is the result of a multiyear investigation that Merlino's lawyers, Edwin Jacobs and John Meringolo, have characterized as thin on evidence, mishandled by agents, and aimed at dismantling an organization they say doesn't exist.

Forty-six purported mobsters and associates were swept up in the dragnet as authorities nearly two years ago unsealed their indictment detailing the workings of an entity described as the "East Coast La Cosa Nostra Enterprise."

The document sketches out a loose alliance of mob crews in New York; Philadelphia; Springfield, Mass.; and Boca Raton, Fla., forced to pool their resources and income streams as the glory days of the Mafia faded into the past. Members – who hailed from the Genovese, Gambino, Lucchese, Bonanno, and Philadelphia families – allegedly committed crimes ranging from extortion and arson to credit-card fraud and selling illegal cigarettes.

And at the organization's top, prosecutors allege, sat a triumvirate of aging dons: Merlino and two Genovese capos – Pasquale "Patsy" Parrello, 73, of the Bronx, N.Y.; and Eugene Onofrio, 75, of East Haven, Conn.

Together, the indictment says, the organization "promoted a climate of fear in the community through threats of economic harm and violence, as well as actual violence."

Forty-four of the 46 defendants — including Parrello — have cut deals with the government to plead guilty, and late last year U.S. District Judge Sullivan postponed Onofrio's trial indefinitely, citing undisclosed health concerns.

That will leave Merlino alone at the defendant's table. But Jacobs and Meringolo have argued in court filings that the government's depiction of a unified Atlantic Coast Mafia enterprise is a fantasy driven by government lawyers and agents eager to build a blockbuster mob case.

‘Too many rats’

Their client maintains that he wouldn't know — he's retired from mob life for good.

It's a line Merlino has perpetually repeated since he was released in 2011 after more than a decade in federal prison for racketeering, gambling, assault, and weapons convictions and immediately relocated to Florida.

Merlino and his lawyers declined to discuss the current case before it goes to trial. But they have cited in court papers a 2013 interview the reputed boss gave to mob writer and former Inquirer reporter George Anastasia as a more accurate representation of what, these days, "Skinny Joey" is about.

"I want no part of that," Merlino said of the mob at the time. "Too many rats."

It's clear that, at least in some ways, Florida has changed him.

The Merlino of Boca Raton is a bronzed, buffed-up, and slightly graying version of the rail-thin, charismatic Philly gangster of the '90s, who drew the ire of Philadelphia's feds as he openly marched in the Mummers Parade while raising hell on the streets in the city's particularly bloody mob war.

He is starting to show his age: A hospitalization for heart blockages earlier this month delayed his trial by two weeks.

And although for a time Merlino was peddling his mother's South Philly recipes at an eponymously named restaurant at which he served as maître d', he has personally adopted a more beach-friendly diet – one that apparently flummoxed his mob associates.

"He's fasting. Since … Sunday, he hasn't eaten," said one purported gangster of Merlino in a secretly recorded 2013 conversation — one of hundreds that prosecutors have amassed to play for jurors at trial.

According to a transcript, Merlino's driver, Brad Sirkin, responded: "But he don't weigh nothing. He's fasting since Sunday? … On purpose?"

Running Philly mob in absentia?

The FBI has never been convinced of Merlino's claims of reform.

Since nearly the day of his 2011 release, a swarm of agents from New York, Florida, and Pennsylvania and wire-wearing ex-mobsters turned informants have trailed his every step to catch anything they might be able to use against him.

They thought they had him in 2014, when a judge in Philadelphia revoked his probation and sent him back to prison for four months for refusing to answer questions about his income and associating with an old mob pal at a Florida cigar bar. But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit overturned that ruling and set Merlino free.

The reason for the continued scrutiny, prosecutors assert, is that Merlino – despite his claims to the contrary – is still running the Philadelphia mob, in absentia.

"Upon [his] conclusion of supervised release … he began working in earnest to rebuild the Philadelphia Crime Family," prosecutors in New York wrote in court papers in December. "Merlino played a role that was less ostentatious [because] he was wary of getting caught due to the increased scrutiny he knew he faced."

Merlino may have told his probation officers back then that he was making money working for a marketing and advertising firm, but prosecutors now allege that his checks were backed by laundered funds generated by a $157 million health-care fraud scheme.

The conspirators — all eight of whom have pleaded guilty in a separate case in Florida — paid kickbacks to doctors and pharmacists who knowingly wrote and filled bogus prescriptions for compound pain creams, defrauding insurers that covered the costs at about $500 to $1,000 a tube.

Meanwhile, Merlino allegedly also was taking cuts from an offshore sports bookmaking operation based in Costa Rica. Prosecutors say they have recordings of the Philly don acting as a supervisor for the operation and interceding to settle internal disputes.

But those recordings — made by John Rubeo, the wire-wearing mob associate and cooperator at the center of the case — may give the defense its biggest break at trial.

Two FBI agents were disciplined and removed from the case after an internal investigation showed they had failed to keep all of Rubeo's text messages while handling him as an informant. They also did not file full investigative reports after all of their meetings with him.

Although prosecutors say the lapse was merely a failure to follow internal protocols, Merlino's lawyers have signaled in court filings that they intend to argue that any evidence stemming from Rubeo's cooperation is tainted as a result.

They already have lobbed attacks at the past of other government witnesses, including Bonanno mob capo Peter "Pug" Lovaglio, who flipped sides after he was arrested for smashing a cocktail glass in the face of an ex-NYPD officer at a Staten Island sushi lounge.

As for Merlino, his defense lawyers say, the tapes prove that he's left such old-school mob street violence behind.

"It's easy to kill somebody," he opined to two purported associates in a transcript of a 2014 conversation. "I can tell you, 'Listen, drive me home right now,' get in the car and … shoot you in the … head."

But, Merlino continued: "It's better when you save a friend. I would never put nobody in harm's way. And we're all friends here."