Why is 1 in 10 Philly inmates still confined 'in the hole'?

More than 600 people are currently in segregation in Philadelphia jails. That's more than 11 percent of the current jail population. Many of them are sentenced for 15, 30 or even 60 days. The U.N. calls stays of 15 days or longer inhumane. By comparison, the Bureau of Justice Statistics in 2015 reported that nationwide just 2.7 percent of jail inmates were in solitary at any given time, based on 2011-2012 data. It found just 5 percent of all jail inmates had spent 30 days or longer in isolatio

It was supposed to be one of the least restrictive forms of incarceration the city has to offer: a six- to 23-month term in a Philadelphia jail, with work release.

Then, Cody Carter was caught with a cellphone. For that violation, he said, he spent six months in segregation. That typically means at least 23 hours a day locked in a narrow cell, either in isolation or with a cellmate.

"It's an experience that you can only live to understand. That's how raw it is," he said. "Especially the first 45 days were hell: You get nothing, no toiletries but the soap they give you, a dirty towel. It's just a gruesome experience."

It also appears to be a strikingly common one: More than 600 people are currently in segregation in Philadelphia jails, officials disclosed at budget hearings this month. That's more than 11 percent of inmates. Many are sentenced to segregation for 15, 30, or even 60 days at a stretch.

By comparison, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), in its most recent report, published in 2015, found that nationwide just 2.7 percent of jail inmates were in segregation. Just 5 percent had spent 30 days or longer in isolation.

Mike Dunn, spokesman for the Kenney administration, said in an email: "The use of segregation is not something we take lightly. We are committed to finding other options and to enhancing therapeutic services."

But, he added, "its use here is in line with other peer cities."

Yet at New York's Rikers Island, the confinement rate is just over 1 percent; the jails there worked with the Vera Institute of Justice to reduce the rate from 5.9 percent in 2014.

One major difference is that, while New York two years ago capped solitary stays at 30 days, here in Philadelphia even minor, nonviolent infractions can lead to 15 days in segregation. And, while New York has banned punitive segregation for inmates under 21 years old, Philadelphia has no such rule. Since the city said two years ago that it would seek to stop placing juveniles in segregation, it has instead increased the practice.

Bruce Herdman, medical director for the Philadelphia Department of Prisons, said at a budget hearing that the department will begin providing 10 hours of therapeutic out-of-cell time each week to those in segregation.

"The literature and the courts have decided around the country that [segregation] causes the deterioration of existing mental-health problems, and it also causes mental illness," he said.

The U.N. has called solitary terms longer than 15 days "torture," given the physical and psychological effects. One recent analysis of New York state prisons found the rate of suicide attempts and self-harm were 11 times higher in segregation than in the general population.

Experts say solitary can be particularly harmful for young people, as it can interfere with neurological and social development. The suicide of Kalief Browder, who spent two years in solitary at Rikers Island after being charged with stealing a backpack, underscored the risks.

Philadelphia prison officials do not use the term solitary confinement. But there is disciplinary detention and administrative segregation; in either, an inmate could receive as little as five hours per week out of cell.

Jurisdictions around the country have been working to reduce solitary. For example, Harris County, which includes Houston, cut its segregation rate in half, to about 1 percent, the Houston Chronicle reported recently. The American Correctional Association also issued new policies in 2016 barring long-term restricted housing for youth and people with serious mental illness.

"There's definitely been a sea change," said Sara Sullivan, director of Vera's Safe Alternatives to Segregation program.

She said jails have been able to reduce reliance on solitary using an array of tactics: providing staff with crisis-intervention training to de-escalate before incidents occur, creating special diversionary housing for people with mental illness, introducing alternative punishments, or even incentivizing positive behavior.

"A lot of staff in places at the forefront of this talk about what a better environment there is once they've done this," she said.

Here in Philadelphia, officials said changes were "currently in the making" to keep juveniles out of long-term segregation when the Inquirer and Daily News first reported on the issue two years ago. At that time, the newspapers reported that juveniles had been placed in segregation 41 times in 2015, for an average of 32 days.

Since then, however, the practice has increased: In 2016, juveniles were placed in segregation 72 times, for an average of 36 days. From the start of 2017 through the end of March 2018, segregation was imposed 70 times, for an average of 32 days.

Some young people described contemplating or attempting suicide while in segregation.

One, Jetson Cruz, wrote about his experience last year for a planned City Council hearing that was canceled and has not been rescheduled. In the testimony, obtained by the Inquirer and Daily News, Cruz said that at age 17 he was placed in isolation six different times, five for 30 days or longer.

He described 23 hours or more alone in a small cell. When he left the cell — a reprieve he said sometimes lasted only 15 minutes — he was shackled.

"It makes you become secretive," he wrote. "It changes your personality. … You feel real useless, and like there is no purpose to life. You lose a lot of weight and become desperate."

Still, Philadelphia prisons spokeswoman Shawn Hawes said segregation is necessary for safety and security reasons. Asked for further information, she directed all inquiries to the Right to Know law.

Through a Right to Know request, the newspapers obtained the Philadelphia prisons' disciplinary hearing logs, which provide a window into how and why segregation is meted out.

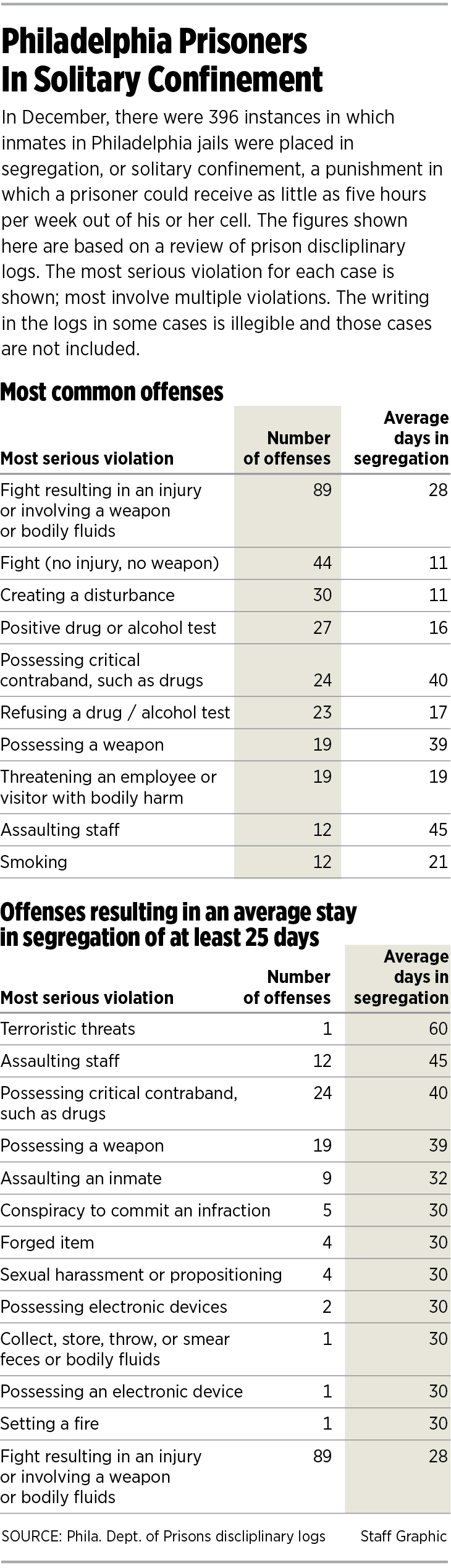

According to those records, in December 2017 alone inmates were placed in segregation 396 times, for an average of 22 days each. In some cases, the disciplinary hearing officer recommended additional administrative segregation, which can be tacked on to punitive sentences indefinitely, as happened in Cody Carter's case. (Administrative segregation is not a punishment but is deployed for safety reasons.)

While other punishments are available — ranging from counseling to restricted privileges to reprimands — these are rarely imposed. In December, just eight individuals were reprimanded, eight were assigned extra work hours, and three were ordered to pay restitution.

The most common infraction was fighting; for that, sanctions ranged from seven days for a minor scuffle up to 60 days for a fight involving a weapon or resulting in an injury.

Three-quarters of segregation terms met or exceeded the 15-day stretch the U.N. defines as "inhumane."

The maximum terms of disciplinary detention, set out in the prison's own policies, were also obtained via an open-records request: seven days for a minor infraction (say, creating a disturbance); 15 days for multiple minor infractions arising from one incident (for example, refusing to comply with an order, being disrespectful, and breaking a posted rule are all listed as separate offenses); 30 days for a major or critical infraction (these range from smoking to assaulting staff); and 60 days for multiple major or critical infractions related to one incident.

For those in detention, 10 hours of weekly out-of-cell time would be a significant improvement.

For those in detention, 10 hours of weekly out-of-cell time would be a significant improvement.

But Hawes said it would be premature to say when the policy would launch, what the "therapeutic" offerings would be, or whether there is funding in place for the initiative.

Some recent inmates said that even in general population, they barely got that much time out of their cells, due to frequent lockdowns.

Still, Carter, 27, of Roxborough, said disciplinary detention was far worse.

Locked up for his first-ever conviction, on charges of harassment, assault, and unlawful restraint, he described spending 23 hours a day in his cell, a narrow room with just two beds and a combination toilet/sink. (Philadelphia is one of an unknown number of jails that at times double-cells inmates in solitary, with sometimes volatile results. Sullivan said no research has been done on whether the practice is more or less harmful than traditional isolation.)

"There was no place to go but your bed," Carter said. "I seen people sleep the whole 45 days."

Later, in administrative segregation, he got a job on the cell block that allowed him a bit more freedom. He said that's what kept him sane.

According to internal records obtained by the Inquirer and Daily News, there were two suicides and 20 attempts in the jails from February 2017 through January 2018.

"I would hear, a few cells down from me, a guy trying to hang himself," Carter said. "People was literally going crazy, yelling, 'I'm going to kill myself!' Most of those guys were bluffing just to get out of their cell, get some type of attention. But there were a few guys who were serious."