A little over a week ago, Sam Katz spoke to John F. Street's class at Temple University. Afterward, the onetime mayoral rivals turned political soul mates were seen huddling together for a couple of hours, prompting a cadre of usual suspects in the political class to wonder what they were cooking up. Was Street once again urging Katz to make one last mayoral run?

It's never too early for rumor. There is speculation that Councilman Bill Green and mayoral aspirant Tom Knox recently reached an accommodation that would sideline Green in 2015. If so, would that provide an opening for Katz, with the help of Street?

When I checked in with Katz, I didn't get a sense of any impending candidacy. I did, however, find a much deeper story. He began by conceding that being the city's mayor has never left his radar screen. After all, Katz first set his sights on being mayor of Philadelphia when he was 7.

His parents took him to the Washington Square open house of uber-reformer Richardson Dilworth, and young Sammy watched the mayor welcome citizen after citizen into his home. The mayor even spoke to him, and seemed interested in what this boy had to say. Katz sensed that "being mayor is cooler than being a ballplayer or a fireman," a suspicion that was cemented by the time he, as student council president at Samuel Gompers Elementary, introduced Dilworth at a school assembly.

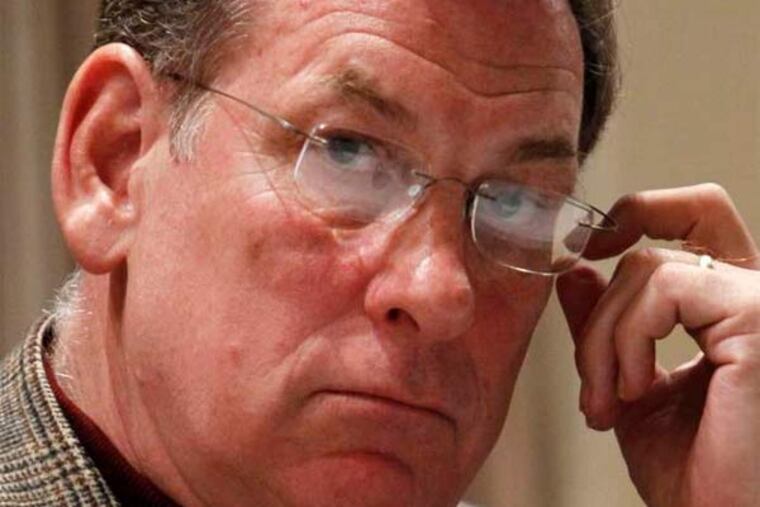

But Katz is now 63; I've known and been friendly with him for 20 years, and you get the sense that he has a newfound perspective. He has been defeated for mayor three times, but he has never had a public moment of Nixonian bitterness, no teeth-clenched snarl that we would no longer have Katz to kick around.

Instead, in a town where politicos tend to nest before bequeathing their elective offices to their offspring, as if Council seats were Eagles seat licenses, Katz has done what so few have: successfully reinvented himself, as a filmmaker and historian.

Last week, Katz released an uplifting trailer for his film, Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, three installments of which have already run on 6ABC. (The next one airs June 20.) This week, he's launching a social-media campaign, with a cool trailer as its centerpiece (you can see it at historyofphilly.com), to generate buzz about the first and only comprehensive history of the city he loves, a city that hasn't always loved him back.

Katz's history documents a time when Philadelphia was always in a state of becoming, when its leaders were, by their very nature, transformational. Somehow, something has been lost. Vision no longer seems to apply in politics.

"Too many, once they're inside electoral politics, discover that to be successful they have to sacrifice their aspirations to change the city in order to win," he says. "They win and realize, 'I want to stay here,' and they say, 'I'll do it in my second term.' And then the day after they're reelected, they're a lame duck."

Not a bad summation of Mayor Nutter's administration, which has come to perfect the art of kicking potentially transformative issues down the road. That's why Katz's series strikes me as an important contemporary undertaking, because it can jump-start a conversation about what kind of city ours might become.

"You can't envision where you want to go if you have no idea where you've been," says Katz, who has been a necessary thorn in Nutter's side as chairman of the Pennsylvania Intergovernmental Cooperation Authority, which oversees the city's finances. "Is there a consensus for what the future of the city is? I don't think so."

Yet Katz's series is about the ideas that have moved us forward in the past - and about what it will take to get us moving again. He chronicles Dilworth's cleanup of local politics, and the groundbreaking 1947 Better Philadelphia Exhibition of city planner Ed Bacon, in which the whole city played a role in its own reimagining. Thousands of Philadelphians trekked to Gimbels at Eighth and Market to view an elaborate before-and-after model of Philadelphia.

Spending time with Katz is like sitting in an urban-studies classroom. Recently, he tutored me in a different kind of "structural deficit" in Philadelphia's budget: Thousands of city blocks that once had, say, 60 homes on them now have fewer than 10. That those streets still receive city services creates an inherent inefficiency - something no one is systematically addressing.

Then there's the pension crisis - this year, 16 percent of the general fund will go toward pension payments. It's not sustainable, but our so-called leaders understate the size of the problem with rosy projections on investment returns.

"Delusion," Katz says, "is not a great strategy for governing."

Katz is right when he says politics - nationally as well as locally - has become a place that doesn't produce change. It's no longer the place where competing visions for the future are honestly debated. But his latest project is a reminder that we can hold those conversations ourselves. After all, in a corrupt, one-party town, change doesn't happen by government - it happens by petitioning government. So, rumors notwithstanding, I suspect Sam Katz will continue telling stories, trying to jump-start a vision-based civic dialogue. He'll do so because he can't help himself.

"I guess because I started off with this ambition to lead the city, that I learned to love it," he says, breaking into a mischievous smile. "Even when it has occasionally kicked the crap out of me."