Dwight Evans offers lessons in getting things done

A veteran Philly pol tells his story in a new book.

A LOT'S BEEN written about Philly Democratic Rep. Dwight Evans during his 30-plus years in office, and much of it hasn't been pretty.

There were electoral flops for lieutenant governor, governor and (twice) mayor.

There were dustups over his West Oak Lane Charter School, his $1 million taxpayer-financed West Oak Lane Jazz Festival, his habit of (legally) accepting gifts, viewed by many - me included - as just plain wrong.

So it's easy to write Evans off: another corruptible career pol in a legislature and from a city with ample examples of the same.

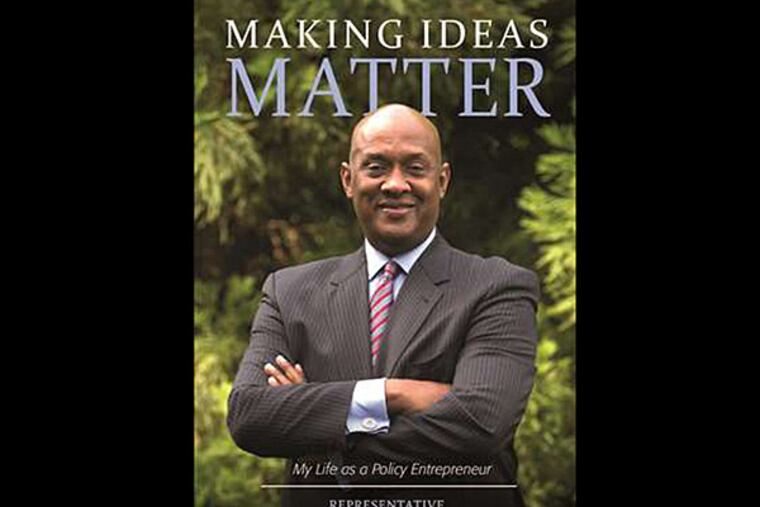

But now Evans is writing back, telling his side of the story in a just-published book, Making Ideas Matter: My Life as a Policy Entrepreneur.

"Policy entrepreneur" sure sounds better than career pol. And his side of the story stresses the good he's done through use of political power.

It's written with Bill Ecenbarger - former Inquirer reporter, author of Kids for Cash (The New Press, 2012) on the juvenile-justice kickback scheme that led to the 2009 indictments of Luzerne County judges - and published by Penn's Fels Institute of Government, which gets all profits.

Reading it might change some thinking about government, politics and Evans.

Or not.

It has self-serving, self-directed kudos.

It has details on using clout and cash to get what he wants.

But it also offers examples of politics working and tax dollars, even in the much-maligned form of "WAMs" (walking-around money), serving a greater good.

If you don't like government, you won't like this book. If you've lost faith in politics, it might offer some solace.

Either way, it's an interesting read.

Elected in 1980 at age 26, Evans rose to become the first African-American head of the House Appropriations Committee, a powerful post he held 20 years.

He grew up in Germantown until his working-class parents separated. He, his mother and siblings moved to West Oak Lane when he was 13.

He worked after school and Saturdays (lied about his age) in the kitchen of Rolling Hill Hospital in Montgomery County, three bus rides and 45 minutes from home, for $1.10 an hour.

Meanwhile, his mother forged their home address so he could attend a better junior high.

In college at La Salle, he organized a black student union and was its first president. He graduated early, taught in a city school, worked for the Urban League, became a community activist, then ran for office.

He would not be one of those too-typical lawmakers who do little, are never heard from and win re-election by sending out birthday cards.

In the '80s, he pushed for a new convention center, which he saw as good for the city. But he angered other black lawmakers who viewed the project as a boondoggle for white businessmen. Black talk-radio hosts called him "Uncle Tom."

He brought businesses and jobs to his district, especially Ogontz Avenue, and started to get attention.

In the '90s, campaigning for appropriations chairman, he drove around the state to meet new lawmakers. An Elk County lawmaker's 10-year-old son told him he was the first black man he'd ever seen in person.

Chosen as chairman, he used "WAMs": $500,000 for a statue of World War II Gen. George Marshall in Uniontown for support on a key tax vote from a reluctant fellow Democrat; he got the Philadelphia Orchestra money to go to China, and the orchestra did free annual concerts at a high school in his district.

But he got core-function stuff done, too: $1 million for a township in far-west Fayette County, where residents had no running water, and a statewide program bringing fresh-food stores to poor areas.

The latter won praise from Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and from first lady Michelle Obama. When she came to Philly to launch her 2010 "Let's Move" fight against childhood obesity, she announced plans for a national program based on Evans' effort.

Over time, he angered Democrats by working with Republicans. He angered teacher unions by supporting charter schools and a state takeover of the school district. The power he amassed, the deals he did and the enemies he made cost him his chairmanship in 2010; his colleagues voted him out.

But he's still in the House, was active in recent passage of the transportation bill and, at 59, despite his hits, he remains standing and engaged.

His book is his story, so it slants his way. But remember this: Eight other legislative leaders went to prison during his appropriations reign as he kept working. And there are people in politics pushing substantive policies to help constituents.

Ideas do matter. Individuals can make a difference. Evans' book reminds us of that.

Blog: ph.ly/BaerGrowls

Columns: ph.ly/JohnBaer