Democrats have one-party rule in Trenton. Why can’t they agree on taxes?

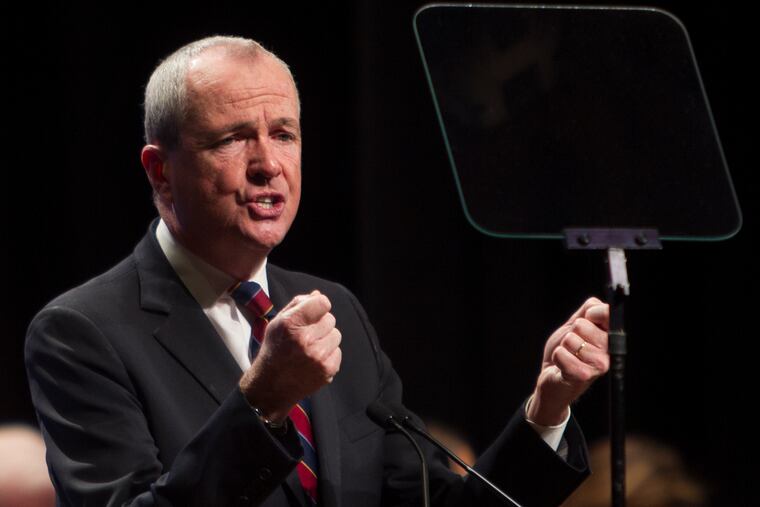

Five months into his term, Gov. Murphy has moved New Jersey sharply to the left after eight years under a Republican governor, enacting a sweeping liberal agenda that includes a pay-equity measure intended to narrow the gender wage gap, mandatory paid sick leave, automatic voter registration, financial aid for college to undocumented immigrants, and restoring Christie-era cuts to Planned Parenthood.

At the same time, political observers said, Murphy, who had never before held elected office, has had a rocky start in dealing with the Legislature.

Chris Christie used to say that when he was elected governor in 2009, his old mentor, former Gov. Tom Kean, offered some advice. "Who's your best friend?" Kean asked. "My wife," Christie replied.

"Not anymore," Kean said, urging Christie to befriend the Senate president, Steve Sweeney.

It was Christie's way of explaining a partnership with a Democrat that was crucial to the first-term accomplishments that made him a national political star.

As with just about everything else, Gov. Murphy has taken a different approach.

"Gov. Christie gave me some good advice in transition. But I just have to say … I'm not ripping a lot of pages out of his playbook," Murphy said in an interview last week. He added that his remark was not related to his relationship with Sweeney — though that would elicit an eye roll from many in Trenton.

Five months into his term, Murphy has moved New Jersey sharply to the left after eight years under a Republican governor, enacting a sweeping liberal agenda that includes a pay-equity measure intended to narrow the gender wage gap, mandatory paid sick leave, automatic voter registration, financial aid for college to undocumented immigrants, and restoring funding cut by Christie to Planned Parenthood.

Those ideas were mostly noncontroversial in the Democratic-controlled Legislature, which had fought for many of them under Christie. Murphy has also positioned New Jersey as a liberal check on President Trump, backing lawsuits to fight the White House on immigration and the environment.

At the same time, Murphy, a former Wall Street banker who had never before held elected office, has had a rocky start in dealing with legislators, including Sweeney. The two men don't particularly like each other, associates of both say, and Sweeney has refused to back the governor's proposed tax hikes, fueling uncertainty around a budget that's due June 30.

While he strives to maintain the diplomacy, Murphy, a former ambassador to Germany, can't always conceal his exasperation. Recounting criticism that his talk of "investing" was just liberal code for "spending," he grew animated. Results don't come cheap, he said.

"You want to move to Mississippi? God bless you. Good luck raising your kid down there. Tell me how the public schools are," Murphy said in the interview in his eighth-floor satellite Newark office. "Let me know how that light rail system is working down there for you, how the institutions of higher ed are doing."

Where Christie made it a priority to cultivate personal relationships with lawmakers, if only so he could learn how to twist their arms and negotiate a deal, Murphy is said to have taken a more hands-off approach, according to interviews with nearly two dozen lawmakers, lobbyists, and other Statehouse observers. Nor has Murphy done much to try to win over George E. Norcross III, the South Jersey political kingmaker and insurance executive who worked closely with Christie, say people familiar with the matter.

Now facing his toughest negotiation in office, Murphy is clashing with members of his own party over his proposed $37.4 billion spending proposal. Legislative leaders have all but balked at Murphy's proposed sales tax hike and a higher income tax rate for millionaires. In total, Murphy wants to raise $1.6 billion through new taxes.

Just weeks before lawmakers must send the governor a balanced budget, Sweeney is threatening to shut down government if Murphy doesn't agree to change the way the state distributes money to school districts. Murphy has ordered state agencies to prepare for a possible shutdown.

There's one-party rule in Trenton, but it doesn't look like it right now.

"I don't think New Jersey is a progressive state. I think it's a moderate state. I think it still is," Sweeney, a union ironworker by trade, said in an interview. "We're socially progressive and fiscally more on the conservative side, especially because of the high taxes in this state."

He said voters "were never going to vote for a Republican" in last year's governor's race. "It's not a mandate," he said of Murphy's 14-point win. "He had a solid victory. And if you read all the polls I read, ask the people if they want to raise taxes. That's not what they really want."

Sweeney voted in favor of a so-called millionaires tax when Christie was governor but says the federal tax law changed his mind, because it set a cap on a popular deduction that for years had softened the pain from the nation's highest property taxes. Some in Trenton think that's just political cover to block Murphy's agenda.

Murphy argues that the state needs sustainable revenue to invest after years of cost-cutting from Christie, a Republican who left office as the least popular governor on record.

Murphy wants to expand pre-K, make a down payment on a plan to make community college tuition-free by 2021, legalize and tax recreational marijuana, and boost funding for education, public workers' pensions, and transportation.

Democratic leaders in the Legislature say they support many of those goals, minus the community college plan, and it's too early to tell whether the administration and lawmakers will reach a compromise on marijuana by the end of the fiscal year, June 30.

Sweeney has said he favors a corporate tax increase, and Assembly Speaker Craig Coughlin has proposed a tax amnesty program to allow delinquent taxpayers to settle with the government.

Some Democrats and other political observers say Murphy hasn't done enough to sell his tax plan to the public.

Though New Jersey is a Democratic state, veteran legislators worry that Murphy's plan would amount to an over-correction to Christie's austerity. Assembly members are on top of the ballot in 2019, and they think they would pay the price for Murphy's budget.

It's almost impossible to imagine parts of New Jersey flipping Republican, but key leaders' districts are more moderate.

Donald Trump won Sweeney's South Jersey district in 2016. Sweeney's home county of Gloucester went to Christie in his 2009 win over incumbent Democratic Gov. Jon Corzine, as did Middlesex County, where Coughlin lives.

"How does a person living in Salem County feel about a sales tax increase? It's not something that excites them," said Assemblyman John Burzichelli, a Democrat who represents the same district as Sweeney.

Some Democrats also point to the 1991 GOP takeover of the Legislature in the aftermath of Gov. Jim Florio's tax hikes. While times have changed, polling shows residents still feel overtaxed.

A May Monmouth University poll found that just 54 percent of residents say the Garden State is an excellent or good place to live, a record low rating based on polling going back to 1980. Property taxes ranked as residents' top concern.

"If we don't start doing things to contain the cost of government, we won't be a Democratic state for long," said former State Sen. Raymond J. Lesniak, who ran against Murphy last year.

Murphy says fears of a 1991 repeat are misplaced, noting that Florio didn't telegraph his tax plans during the campaign. "We inherited a mess. We spoke to that mess every single day on the campaign trail. And we spoke to the solutions, the sustainable solutions, responsible solutions, that were needed to address that mess," he said.

"The public is unambiguous in what they want us to do," Murphy said. "That is so different than what it was then."

Murphy wants to raise the sales tax from 6.625 percent to 7 percent and impose a 10.75 percent marginal rate on income above $1 million. The top current rate is 8.97 percent.

Residents do seem amenable to some tax increases: For example, more than two-thirds favor a higher rate for households that earn more than $1 million annually, according to a March Rutgers-Eagleton poll.

It doesn't help that Murphy and Sweeney started out as rivals.

They ran in a shadow primary for governor during Christie's second term, and Sweeney's camp believes Murphy, a multimillionaire former Goldman Sachs executive, effectively bought the Democratic nomination.

The Senate president lashed out at Murphy for failing to intervene with the New Jersey Education Association — the state's largest teachers' union — as it spent millions on attack ads in an unsuccessful bid to oust Sweeney last November.

They've worked together on a number of legislative initiatives so far, but Trenton observers say the outcome of the budget debate will be a clearer marker of Murphy's standing.

"He's done well in pursuing his progressive agenda," Lesniak said. "It's been a very, very rocky relationship" with the Legislature, he said. "But, there's plenty of time to turn that around."