What we can learn from low Pa. primary election turnout, and why it matters that just 1 in 6 Philly voters showed up

Turnout in Tuesday's primary election was lower in the city than in the rest of the state. Experts cited many reasons for that, and a resultant problem: Uneven voting makes for uneven representation.

Amanda Silberling was part of a distinct minority among Philadelphians last week.

She voted.

Just 17 percent of registered voters bothered to show up for Tuesday's primary — the 825,000 other voters didn't bother, according to official figures.

The city's turnout was low even by statewide standards. Only 18 percent of Pennsylvania's registered voters cast ballots, which means that almost seven million didn't.

That's a shame, said Silberling, who graduated from the University of Pennsylvania the day before voting.

"It's extremely important that people engage in local government and that people educate themselves about every election that they can vote in and talk to their friends also about being aware of what's happening, both on a local and a national level," she said, standing outside the library at 40th and Walnut Streets where she had just cast her vote.

Silberling's precinct has 734 registered voters; 21 of them showed up, a turnout of less than 3 percent.

Although the turnout was typical of a midterm primary, this was no ordinary election, with inducements for voters on the right and left. For Democrats, on fire since President Trump's 2016 victory, this was their first chance to weigh in on federal races. New congressional maps drew a posse of candidates to competitive primary races. On the Republican side, candidates waged a ferocious campaign for the gubernatorial nomination.

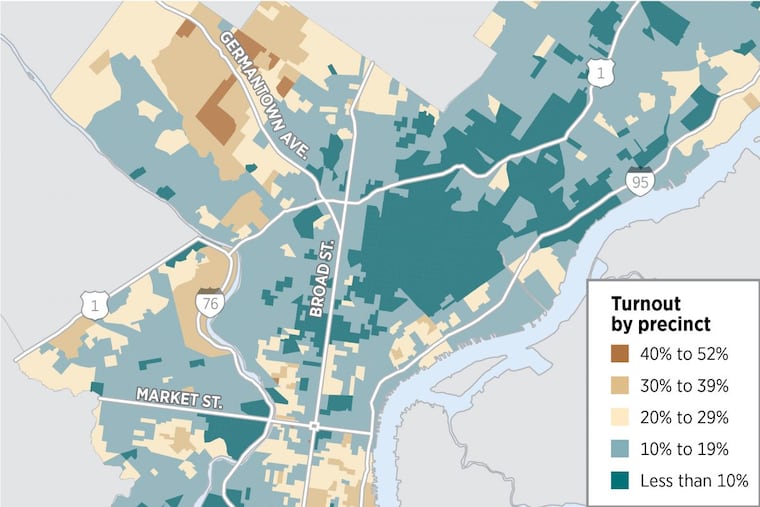

Yet only one precinct, Division 16 in Ward 8 in Rittenhouse Square, cracked the 50 percent turnout mark in Philadelphia; in more than 1,200 of the city's 1,688 precincts, less than 1 in 5 registered voters showed up Tuesday.

Why primary elections have lower turnout than general elections

The act of voting takes just a few minutes, standing in the isolation of the machine, pushing buttons before stepping back out into the real world.

Getting there isn't always that simple. It requires registering, knowing the polling location, the voting hours, and perhaps taking time off from work or figuring out what to do with the kids. Oh, and you have to know the issues and the candidates.

These can be major obstacles, especially for low-income people and the disabled. But for others, voting simply isn't worth the inconvenience. And besides, they might have better things to do.

"I've been moving out and trying to see friends as they leave," said Aria Kovalovich, 22, who lives in Silberling's district and also graduated on Monday — but did not vote Tuesday. "I passed a voting booth and I remembered, and I was like, 'I'm going to sit down and look at the candidates and make a decision and go vote,' and then I just didn't."

"I think I just got wound up in friends leaving and trying to say my last goodbyes," she said.

Inconvenience can be enough to deter voters, even the ones who believe in voting.

"There are far more people who are kind of OK with the idea of going, but they're not itching to get there," said Laura C. Bucci, an incoming political science professor at St. Joseph's University. "Even smaller obstacles can get in the way of that as well. It's that really any obstacle means that people are just not going to go."

Kovalovich's story speaks to some of the reasons turnout is lower in primary elections than in general elections.

"The easiest explanation is that [a general election] is the most likely to mobilize people, people are most likely to hear about that election," Bucci said. General elections can get wider news coverage, so more people know there's an election in the first place, and large, well-funded campaigns can reach voters whom smaller local campaigns might not. General elections also pit parties against each other.

"You can go and know one thing about yourself, and that's that you're a Democrat or a Republican, and you can go from there and pick," Bucci said. "You can't do that in a primary. … You have to know more information, or at least be willing to guess more information."

Some voters also assume that the general election is more important. And although the November election decides who wins office, May might outweigh November in Philadelphia. Democrats dominate the city, almost always winning the general elections.

Voting matters because representation matters

Increasing turnout is about more than civic duty or feeling good — it's about representation. Whose voice is heard? Which issues matter?

When turnout is low, a tiny percentage of the electorate can drive the agenda and shape policy.

Those motivated to vote are more likely to be better educated, more affluent, and older than nonvoters. Different groups may have different preferences for candidates and policies, but only that small group of voters gets heard. And once in office, politicians care more about what their voters say than about their constituents writ large, said Shauna Shames, a political science professor at Rutgers-Camden.

"Of course, if you're somebody who takes your job as representative seriously, you're thinking about everybody," Shames said. "But within 'everybody' there are different circles of importance, and the people who are going to vote the next time, that's a big circle. You're probably paying more attention to their issues."

That means uneven turnout among interest groups is more significant than low turnout.

"Young people have usually pretty different political issues from older people; lower-income folks tend to be more supportive of government programs and services than more affluent people are," said Mallory SoRelle, a government and law professor at Lafayette College in Easton.

Sophie Bodek, 21, another Penn student who graduated Monday, had representation in mind when she thought about Tuesday's election.

"I feel like I should be voting in all of the elections, just because you should be involved in politics. Especially in this election, after there are so many women running and other people who should have their voices heard," she said. "And so I should be more attuned to that and try to elect different, more diverse voices to office. So that, especially, this election, is important. But otherwise I think it's a civic duty that you ought to be doing."

Turnout might be higher than we think. Then again, maybe lower

Turnout numbers aren't necessarily accurate, and that's not a wholly bad thing.

In the case of the Penn precinct, it's unclear how many of those registered voters still live there. Once they graduate, they may never vote in Philadelphia again.

But for several elections, they'll remain on the voter rolls. For highly mobile populations, including homeless people and low-income families that move often, updating voter registrations can be near the bottom of a long list of things to do after each move.

Officials have to balance two noble but competing interests: Having accurate and up-to-date voter rolls is important; it's also important not to disenfranchise people, and experts said registration already poses a barrier, and being unnecessarily purged from the rolls can exacerbate the problem.

"List maintenance is vital to the integrity of elections," Jonathan Marks, the state's elections commissioner, said in an email. "It is also essential that the procedures be carried out with precision and due diligence to avoid the inadvertent elimination of any eligible voters from the rolls."

In Pennsylvania, election officials can change registrations based on certain information provided formally: A change of address with the postal service, a change of address with PennDot, a death certificate from state or local officials.

Otherwise, it takes time. Years.

After five years, registrants who have not voted in two federal general elections are sent a notice in the mail. If they do not respond and do not vote for an additional two federal general elections, they are removed.

"You're missing 14 elections before you're inactive. That means all those presidentials and gubernatorials and mayorals and all that in-between," said Philadelphia City Commissioner Al Schmidt, an election officer. "Fourteen elections in a row is a really significant number of elections to miss."

So a college freshman who registers to vote might never again vote at that address, but will remain on the rolls for several years after graduating. And for every election in between, that ghost student contributes to low turnout.

"Imagine, year after year, students come and students go, but their voter registration lives on past the time that they've left the city," Schmidt said. "That is not a voter-fraud situation. That is inactive voters who remain on the rolls because of state and federal requirements for making them inactive and then canceling them."

On the other hand, many eligible voters do not register, and the turnout figure does not take them into account.

In the end, primary elections are decided by a tiny minority of all the adults who could vote.

Bodek, the Penn student who said she was particularly interested in last week's election because of the diverse array of candidates, went home to the suburbs to be with her family Monday afternoon after commencement. The few minutes it would have taken to vote would entail a lengthy round-trip drive.

So instead of being one of the 21 people who voted in her precinct, Bodek was one of the 713 who didn't.

"I do feel a little bad," she said. "But clearly not bad enough to vote."

Staff writer Jonathan Tamari contributed to this article.