Mexican bishop dares to speak out in public

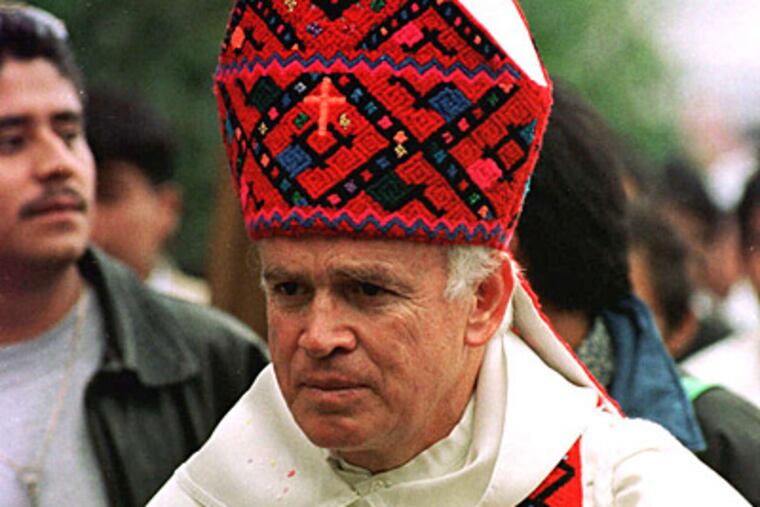

MONCLOVA, Mexico - The white-haired bishop stepped before about 7,000 faithful gathered in a baseball stadium in this violence-plagued northern border state. He led the gathering through the rituals of his Mass, reciting prayers echoed back by the massive crowd. And then his voice rose.

MONCLOVA, Mexico - The white-haired bishop stepped before about 7,000 faithful gathered in a baseball stadium in this violence-plagued northern border state. He led the gathering through the rituals of his Mass, reciting prayers echoed back by the massive crowd. And then his voice rose.

Politicians are tied to organized crime, Bishop Raul Vera bellowed while inaugurating the church's Year of Faith. Lawmakers' attempts to curb money laundering are intentionally weak. New labor reforms are a way to enslave Mexican workers.

How, Vera asked, can Mexicans follow leaders "who are the ones who have let organized crime grow, who have let criminals do what they do unpunished, because there's no justice in this country!"

In a nation where some clergy have been cowed into silence by drug cartels and official power, Vera is clearly unafraid to speak.

His realm is a wide swath of Coahuila, a state bordering Texas that's become a hideout for the brutal Zetas drug cartel. It's where the current governor's nephew was killed in October and the former governor, the victim's father, resigned last year as leader of the political party that just returned to power with newly inaugurated President Enrique Pena Nieto.

Marked by his unvarnished speech, the Saltillo bishop's voice carries beyond his diocese here, especially when he weighs in on hot issues such as drug violence, vulnerable immigrants and gay rights.

In late 2007, Mexico City's Human Rights Commission denounced death threats against Vera and a burglary of the diocese's human rights offices. The following year, after Coahuila became the first Mexican state to allow civil unions for gay couples, a move the bishop endorsed, Vera was invited to speak at a U.S.-based conference for a Catholic gay and lesbian organization. In 2010, he was awarded a human rights prize in Norway.

Anonymous critics have hung banners outside the cathedral asking for what they called a real Catholic bishop. And last year, the 67-year-old was summoned to the Vatican to explain a church outreach program to gay youth.

Vera, who has had government bodyguards before, said he was forgoing similar security despite the criticism and threats. Such measures were rare and frowned upon in Saltillo, he said.

"I'm not the only one exposed; there are lots of people exposed who work with immigrants, with the missing," Vera said. "How do I cover myself? Them?"

Mexico's Bishops Conference did not respond to repeated requests for an interview about Vera. The church's hierarchy in Mexico did issue a statement in 2010 congratulating Vera on his human rights prize, and last year, the church condemned anonymous threats against him.

Vera's office often lends more weight to his words, especially when he speaks up about human rights, said Emiliano Ruiz Parra, a Mexican journalist and author of a new book that portrays Vera and other "black sheep" of the church in Mexico.

"Among the defenders of human rights he is the one who hedges the least; he says things the way they are," Parra said before Pena Nieto's Dec. 1 inauguration. "He's not afraid, for example, to take on the president, the one who's leaving or the president-elect."

An industrial hub on the high desert about an hour west of Monterrey, Saltillo had long been known as a quiet haven in Mexico, distinguished by its auto manufacturing and a modern museum exhaustively detailing the surrounding terrain.

In recent years, however, the area has fallen victim to the drug violence plaguing other parts of Mexico. In 2011, 729 murders hit the state, compared with 449 the year before and 107 in 2006, according to preliminary figures released by the government this summer. Four bodies were found hanging from a Saltillo overpass earlier this month.

Vera arrived in Saltillo in 2000, after serving as the co-bishop in a deeply divided diocese in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, where Zapatista rebels were battling government troops. He came with a reputation as a social crusader.

"Ever since I arrived here, as I came from Chiapas and I wasn't a person who was going to support the government, since this moment they decided that my image needed to be restrained," Vera said.

In February 2006, Vera celebrated Mass at the Pasta de Conchos coal mine where 65 miners had perished and spent days with their families hammering the mine's owners, government officials and union leaders for dangerous working conditions.

Vera has also demanded investigations into the thousands of migrants who have gone missing while passing through the state and clamored for a DNA database to identify bodies.

What has drawn perhaps the most controversy has been Vera's stand on gay rights, which even caught Rome's attention. In 2001, the Rev. Robert Coogan, an American priest in Saltillo ordained by Vera, suggested starting an outreach program to gay youth after a teenager came to him when his parents threw him out of the house. Vera lent his support to the program, and later escaped reprimand when called to the Vatican to explain it.

"It flows out of his conviction: The church is for everyone," Coogan said.