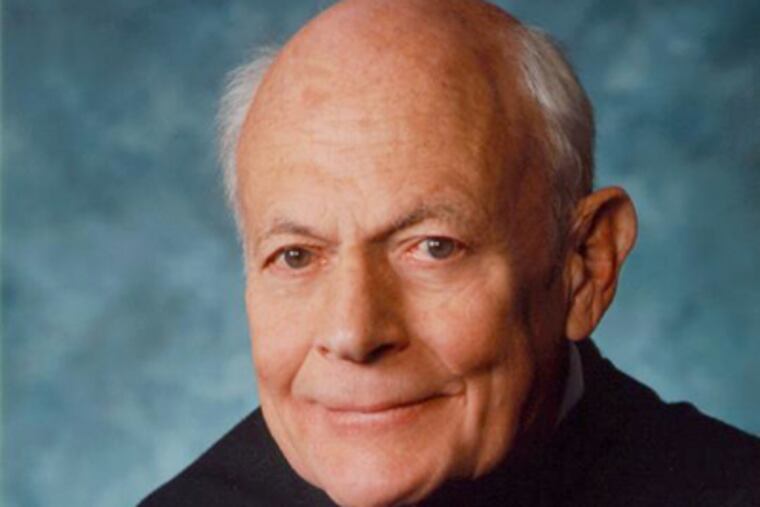

Louis Pollak, federal judge, dies at 89

U.S. District Judge Louis Pollak, a former dean of the Yale and University of Pennsylvania Law Schools and a seminal figure in the litigation emerging from the early civil rights movement, died Tuesday at his home in West Mount Airy after a long illness.

U.S. District Judge Louis Pollak, a former dean of the Yale and University of Pennsylvania Law Schools and a seminal figure in the litigation emerging from the early civil rights movement, died Tuesday at his home in West Mount Airy after a long illness.

He was 89.

Judge Pollak, who began his legal career as a clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Wiley Rutledge, played a critical role in the legal battles over racial segregation. He forged a close friendship with former U.S. Transportation Secretary William Coleman while the two served as Supreme Court clerks from 1949 to 1951 and then later when they went to work at the New York law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

There, they practiced commercial law during the day but spent evenings in Harlem, hashing out legal strategies at the offices of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The two assisted then-civil rights lawyer Thurgood Marshall in writing the briefs in the Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case and worked late into the night helping Marshall prepare for oral arguments before the Supreme Court. Marshall would later serve on the high court.

"The briefs would not have been as good without him," Coleman said in an interview Wednesday. "He was very bright and made great contributions."

Judge Pollak was raised in Manhattan. His father, Walter, also a prominent civil rights lawyer, helped defend nine young black men accused of rape in the notorious Scottsboro Boys case. President Jimmy Carter named Pollak to the federal bench in Philadelphia in 1978.

He graduated from Harvard College in 1943 and from Yale University Law School, where he was editor of the law review, in 1948.

After clerking for Rutledge, he joined the firm of Paul Weiss, where he again became a colleague of Coleman's. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, when most of the nation's elite law firms would not hire blacks or Jews, Paul Weiss was known for its more broad-minded employment policies. It had hired Coleman, an African American who had grown up in Philadelphia and graduated first in his class from Harvard Law School, after he had been turned down by the elite firms based in Center City.

"Those were exhilarating, marvelous years," Judge Pollak said in a 2010 interview. "In retrospect, it seems inevitable" that legalized segregation would be outlawed, he said. "But we sure didn't know it at the time."

Judge Pollak joined the Yale Law School faculty in 1955, teaching constitutional law, and was named dean in 1965, serving for five years.

He left the law school in 1974 to join the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, where he took over as dean the following year. He had headed the search committee for a new law school dean at Penn and was asked to take the job himself at the end of the process.

"I had no idea that Lou Pollak had so much in common with Dick Cheney - who knew?" Theodore McKee, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, joked during remarks at an April 26 awards dinner for Judge Pollak. Like Judge Pollak, Cheney had headed a search committee, in his case for President George W. Bush, to select a Republican vice presidential candidate. Like Judge Pollak, he got the job.

Judge Pollak was known not only for his intelligence and discernment, but also for his keen eye in selecting law clerks, a disproportionate number of whom went on to clerk for Supreme Court justices.

"He attracted clerks of the highest accomplishment," said Michael Fitts, dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School. He also "had the respect of Supreme Court justices who wanted to hire lawyers who had spent time with him," Fitts said.

Ron Levine, a white-collar defense lawyer with the firm of Post & Schell PC, recalled prosecuting a domestic terrorism case tried before Judge Pollak in the late 1980s that ended in a guilty verdict. When the case concluded, the jurors repaired to a nearby bar for a drink - and invited Judge Pollak to join them.

"It indicated their appreciation of the process," Levine said. "It was a testament to the legitimacy with which Judge Pollak ran the courtroom."

Among Judge Pollak's friends was former Supreme Court Justice David Souter, who wrote a letter honoring Judge Pollak for the April 26 dinner.

It read, in part, "As an appellate judge, I know the gratification that comes from being joined by colleagues . . . finding that Judge Pollak agrees with something one has said or written does more than confirm; it validates one's judgment."

Judge Pollak met his wife, Katherine, when he was a third-year law student and she was a senior at Smith College in Northampton, Mass., and they were married in 1952.

The couple had five daughters. Judge Pollak is survived by his wife and daughters Nancy, Elizabeth, Susan, Sally (a former Inquirer employee), and Deborah, and grandchildren. Services have yet to be announced.