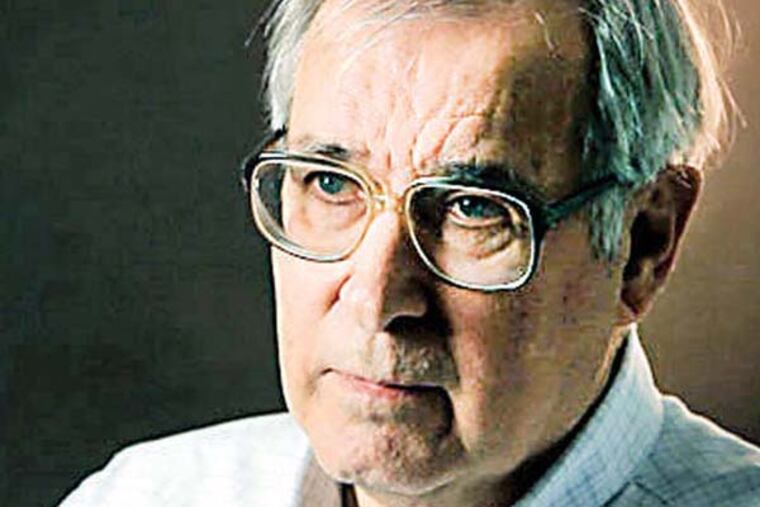

Edward Sozanski, chronicler of the region's art

Edward J. Sozanski, 77, art critic for The Inquirer, who over three decades became a major figure in describing and documenting the city's cultural transformation from regional byway to the national main stage, died suddenly Monday, April 14, in Gladwyne. The cause of death has not been determined.

Edward J. Sozanski, 77, art critic for The Inquirer, who over three decades became a major figure in describing and documenting the city's cultural transformation from regional byway to the national main stage, died suddenly Monday, April 14, in Gladwyne. The cause of death has not been determined.

Whether writing about America's first sculptor, William Rush, or art from Korea's Joseon dynasty, or the way John Cage's musical "scores" looked on the page, Mr. Sozanski always sought to directly engage the art and provide his readers with an utterly independent critical judgment.

Despite his substantial stature and influence as a critic, his focus always remained on the integrity of the art; he was not distracted by institutional marketing efforts or the city's cultural boosterism.

"He used to say that 'I come here to look at the show, form my own thoughts, and share them with the reader,' " recalled Timothy Rub, director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. "He was very blunt about it, even a little standoffish."

Joseph J. Rishel, the Art Museum's senior curator of European painting before 1900 and a longtime friend, characterized Mr. Sozanski as "deeply thoughtful" and "very shy," and wary of institutional pressures on his critical writing.

"He had a show-me side," Rishel said. "He would question everything, going through [a show]. But he was very fair-minded, very fair-minded.

"It's a very sad loss for Philadelphia."

Mr. Sozanski's influence and interests touched virtually everything connected to the city and the art made and exhibited here since he joined The Inquirer in 1982.

He was a sharp critic of the proposal to move the Barnes Foundation from its home in Merion to a new site on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia. After the foundation made the move in the spring of 2012, Mr. Sozanski assessed the new Barnes gallery setting not once, but twice.

"Mother drilled into our fuzzy little heads the importance of first impressions, but she neglected to say anything about seconds," he wrote last September in his second assessment.

The collection is indeed "more accessible" in Philadelphia, he went on to say, but the move "made the collection's quirks, and especially its deficiencies, more obvious."

Mr. Sozanski possessed the frame of a basketball player - he was about 6-foot-5 - although his partner of three decades, the ceramist Marian Pritchard, said he never played the game. His writing and conversation were filled with a mordant - some might say curmudgeonly - wit.

"Making art that serves the people is a noble goal, yet as both the Bolsheviks and the Mexican muralists discovered in the last century, it's not easy to accomplish," he wrote in a 2012 assessment of the Open Air light sculpture on the Parkway, which he dubbed "alfresco Facebook meets science fair."

"Ed's contribution to the cultural life of this city was enormous," said William Valerio, director and chief executive of the Woodmere Art Museum. "He treated his role as critic as a responsibility to report to readers on the art and culture being presented in public institutions for the public good. That drove his writing. If he thought something was not right, he felt a responsibility to say so."

As a result, Valerio said, Mr. Sozanski gained authority and respect.

"Ed made Philadelphia a good place for artists to live, because people knew art was being taken seriously here," Valerio said.

Pritchard said Mr. Sozanski "absorbed life quietly through reading and observing, and released it to others with clear thinking, insightful writing, and wit."

He was, she said, "a good man."

Mr. Sozanski was born in Providence, R.I., and attended the University of Rhode Island and the Columbia University School of Journalism.

Following stints in the communications departments of several colleges - Brown and Yale among them - Mr. Sozanski began his newspaper career as an editor at various newspapers, including the New York Times and the Honolulu Advertiser, returning to Providence as an editor at the Journal and Evening Bulletin, where he eventually became art critic.

"He was always interested in art," said Pritchard. "He was passionate. He just loved it."

In his first piece upon arriving in Philadelphia in September 1982, Mr. Sozanski described an exhibition of Cage scores and prints at the Art Museum.

"Cage is not an artist who brings a flush to our cheeks and or lumps to our throats," Mr. Sozanski wrote. "We are more likely to stare in bewilderment."

But he was hardly bewildered, as his analysis showed. He said the exhibition revealed Cage "as a catalyst who makes art possible rather than an artist who makes art."

That piece was followed by more than 3,300 columns and reviews. Mr. Sozanski, as Valerio noted, would "seek out" art in museums all over the region, and traveled up and down the East Coast before newspaper budget cutbacks eliminated such travel.

He continued to visit all of the area's museums after 2005, when he officially retired, writing for The Inquirer afterward on a freelance basis.

One area of art making in Philadelphia particularly excited him: the explosion of crafts that began sweeping the city three or four decades ago.

From the beginning of his career here, Mr. Sozanski took seriously all manner of media - metal, glass, textiles, ceramics, wood. By so doing, he contributed enormously to the craft renaissance in the region.

"Philadelphia has a lot of crafts, and so there were a lot of opportunities for him to work with one of the strengths in the community," Pritchard said.

In 1983, he contacted the Clay Studio to arrange to see the exhibition American Clay Artists 1983. Pritchard was acting director of the studio at the time.

"He said he had reviewed crafts for the Providence Journal," she recalled. "So he already had an interest in the field."

His final column, which appeared Sunday, assessed the art of metal-furniture craftsman Paul Evans.

In addition to his partner, Mr. Sozanski is survived by a son, James, and a grandson.

Funeral arrangements were incomplete.

Sozanski on an Outsider Artist

Martin "Ramírez has become one of the stars of the untutored cohort, not only for his sad life story but also because his drawings are unusually large and as mysterious as neolithic cave paintings.

"His hermetic images of tunnels, trains, and cowboys framed in prosceniums, while visually compelling, suggest a mind locked in a perpetual cycle of trying to regain a grip on reality.

"Yet Ramírez doesn't ramble; he organizes space skillfully and achieves hypnotic effects through bold repetition of line. Emotionally his drawings are self-contained and offer viewers few entry points, but graphically they are powerful projections."

Review of " 'Great and Mighty Things': Outsider Art From the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection" at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, March 3, 2013

EndText

Sozanski on Wyeth

" 'Ides of March' depicts a large dog lying in front of a stone fireplace whose stygian interior is demarcated by a few glowing embers and iron cooking tools hanging at the left.

"We learn that the dog, Nell, is [Andrew] Wyeth's, and that the fireplace is in his Chadds Ford house. The dog is relaxed but not sleeping, and lovingly defined, down to the bristles on his muzzle. . . .

"The picture is a paragon of equipoise, both in terms of how spaces are precisely calibrated and how the illuminated passages, particularly the body of the dog and the left face of the fireplace, play against the darker ones. Wyeth was aiming for an ideal, and he achieved it."

Review of "The Making of a Masterpiece," Brandywine River Museum, March 31, 2013EndText

215-854-5594 @SPSalisbury