Dirty money

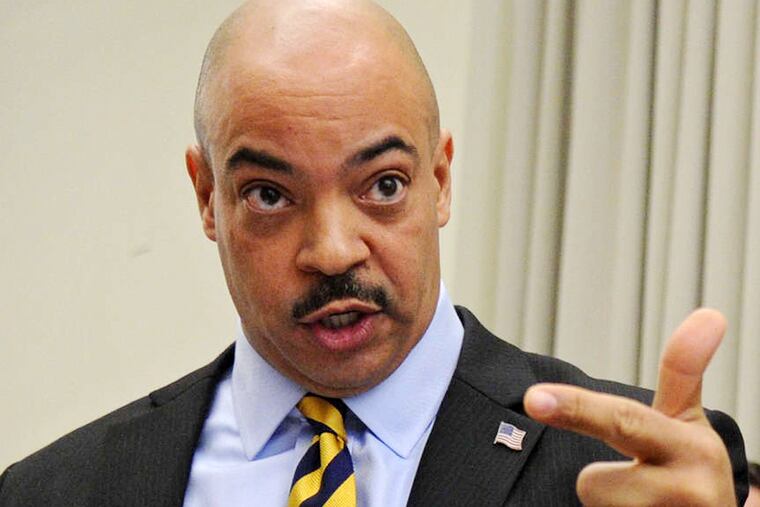

District Attorney Seth Williams has agreed to stop seizing homes and cars from people who aren't even suspected of crimes and haven't been able to contest the seizures in court. It's a belated but welcome retreat from an indefensible practice.

District Attorney Seth Williams has agreed to stop seizing homes and cars from people who aren't even suspected of crimes and haven't been able to contest the seizures in court. It's a belated but welcome retreat from an indefensible practice.

Using the state's civil forfeiture law, which is designed to deprive drug dealers of ill-gotten gains, the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office has routinely thrown innocent people out of their homes on the grounds that investigators believed drug crimes took place in them. The law allows prosecutors to take a property even if the owner has not been accused of a crime and, worse, before a judge reviews the case.

Such unfair confiscations became so commonplace that University of Pennsylvania law professor Louis Rulli wrote of Penn law clinic students regularly representing "law-abiding grandparents whose homes are seized for alleged low-level drug offenses by their grandsons. These elderly homeowners' only sin is providing shelter to extended families."

Williams' office agreed to restrict the practice in a tentative settlement with the Institute for Justice and the Philadelphia law firm Kairys, Rudovsky, Messing, & Feinberg, which sued in federal court on behalf of families whose homes were unfairly seized. The litigation seems to have had a positive impact soon after it was filed last year: The District Attorney's Office has not carried out any property seizures without court review since September 2014.

Under the proposed settlement, future seizures would require "specific, particularized, and credible facts" showing that the city's interest would be compromised by allowing property owners to stay in their homes or continue to drive their cars. Homeowners would no longer be barred from their properties before the cases reach court, giving them a chance to defend themselves. Prosecutors would also relinquish the power to ban family members from properties.

As misuse of forfeiture laws has attracted more scrutiny nationwide, Philadelphia has stood out as one of the worst abusers. The District Attorney's Office seized $60 million in property over the last decade, using the funds to support its work. That has created an unacceptable profit motive for prosecutors to keep seizing property.

An Institute for Justice analysis showed that of 147 home forfeiture cases filed in Philadelphia last year, nearly 85 percent involved a "seize and seal" order allowing authorities to take the property before a judge could determine the propriety of such extreme measures.

Williams has defended his office's enthusiasm for forfeiture, explaining that most of the property seized was cash from alleged drug transactions. But there is no excuse for punishing people merely for being related to someone suspected of a crime.

A settlement preventing such practices would begin to address a stain on Williams' otherwise strong record. Meanwhile, the legislature should take action to assure that the civil forfeiture law isn't paying law enforcers to punish the innocent.