WWII brought ugly sentiments out in the U.S.

For many Americans - young and old - the Second World War occupies a privileged place in popular memory: It was the "Good War" fought by the "Greatest Generation" armed with the "Arsenal of Democracy."

For many Americans - young and old - the Second World War occupies a privileged place in popular memory: It was the "Good War" fought by the "Greatest Generation" armed with the "Arsenal of Democracy."

All wars, however, are complex. The wartime paranoia unleashed by the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor suspended rights and freedoms for many Americans, upending the very notion of citizenship.

During the conflict, suspicion of sabotage led to the forced relocation of more than 150,000 individuals of Japanese, Italian, and German ancestry. Never before had the federal government administered a program restricting the full movement of its citizens solely based on ancestry.

Dec. 7 marks the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor. With the focus on issues of citizenship in this year's presidential election, it is perhaps more pertinent than ever to examine the tenuous historical relationship between "enemy aliens" and "inalienable rights."

This can be charted in the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Archivists have turned up a promotional scorecard for the 1941 World Series - before Pearl Harbor - begging readers to support an anti-Hitler war in the name of American sportsmanship. Lumped into the otherwise German "lineup" is Prince Fumimaro Konoe, the prime minister of Imperial Japan at the time.

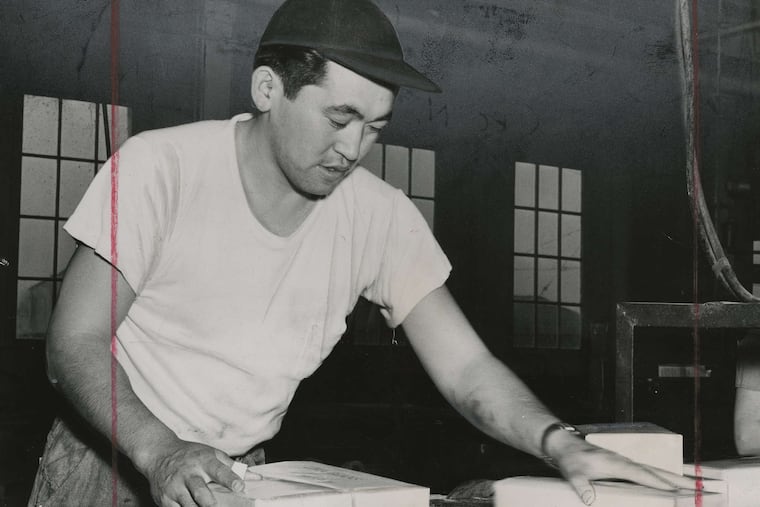

Another collection documents Charles F. Seabrook's frozen-foods business in Bridgeton, Cumberland County. Facing a labor shortage during the war, the company recruited interned Japanese Americans starting in late 1943. Within a year, nearly 1,000 workers had relocated to Seabrook from internment camps, reaching 3,000 by the end of the conflict.

"The future Dr. Hiromi Sato, one of dozen American citizens of Japanese extraction released from Government camps to work at Seabrook Farms," ran the 1944 press account in the Philadelphia Record. "All have withstood acid test of their loyalty, have brothers or other relatives in Uncle Sam's armed forces and are Christians. Sato, 22, was a premedical student at University of California, plans to continue studies in spare time, and resume college after the war. He is also about to become an Eagle Scout."

Further hidden in the stacks was a collection of photographs documenting the experiences of "aliens" at the Gloucester Immigration Station in New Jersey as they awaited deportation, including many foreign nationals from Italy and Germany.

"Uncle Sam's business at the Gloucester Immigration station depends on a steady turnover in that most perishable of commodities, the alien," according to a 1944 edition of the Record. "This is the detention building where some 1,100 deportees are received annually. Three weeks ago business picked up when 117 crew members of three Italian freighters seized by the U.S. in the harbor here were interned."