Descendants look for the full story

I envy Clayton Adams. He is a great-great-great grandson of Solomon Northup, the free black man from New York whose kidnapping and enslavement in 1841 are recounted in 12 Years a Slave, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Unlike me and the students I teach in my African American genealogy class, Adams knows the story of his ancestor's kidnapping, enslavement, and freedom from beginning to end.

I envy Clayton Adams.

He is a great-great-great grandson of Solomon Northup, the free black man from New York whose kidnapping and enslavement in 1841 are recounted in 12 Years a Slave, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Unlike me and the students I teach in my African American genealogy class, Adams knows the story of his ancestor's kidnapping, enslavement, and freedom from beginning to end. Northup wrote about his ordeal in his 1853 book 12 Years a Slave, which became a best-seller. Succeeding generations in Northup's family have read his book and gather annually to honor him in his Saratoga Springs, N.Y., hometown.

The rest of us African American researchers struggle to identify slave owners and to trace slaves with only a first name. Some of my students aren't able to trace their families back to slavery; they're still searching for the maiden name of a grandmother, or trying to find out what happened to a great-grandfather. We can only wish to know as much about our families as Adams does, because the records don't exist.

Yet Adams and his family have this in common with me and others: We don't have the full story of our ancestors' lives.

Unlike Northup's descendants, I didn't grow up learning my family's history. When I began researching my family in 1988, I worried that I wouldn't be able to find my ancestors. I believed that when and if I did find them, they would all be slaves. I was wrong. I discovered that my paternal great-grandmother's family were freedmen who migrated from Tennessee to Ohio in the 1840s; that my great-great grandfather, a former slave, was a private in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War; and that a great-great uncle, who was born free, married an Irish immigrant in Ohio in the 1870s.

And I confirmed a family tragedy.

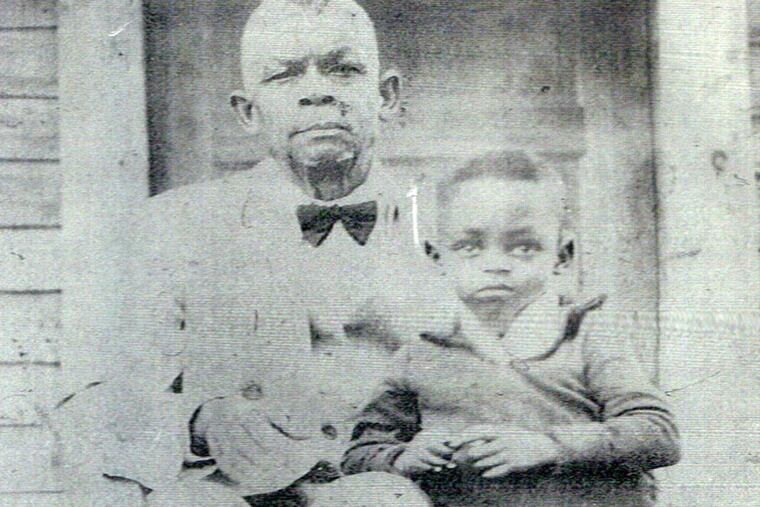

I found a newspaper article that described the September 1879 lynching of my maternal great-great grandfather, Charles Brown, in Wilkinson County, Miss. I found out about the lynching from my granddad Theodore Brown. In response to my question of whether we had any "Kunta Kintes in the family," he told me that his grandfather, a carpenter, was building a house for a white family who had refused to pay him. He told his pregnant wife, "I'm going to get my money." He left her and their seven children at their home in East Feliciana Parish, La., and was never seen alive again.

I hesitated for years before finally attempting to document my granddad's story, believing that I wouldn't be able to find anything about a lynching. But in 2006 I found an article reprinted in a newspaper in his hometown headlined "Outrage and Retribution," that revealed a confrontation between "a colored man named Charles Brown" and Mary Phares. He reportedly threatened Phares with a hatchet and was about to commit a "nameless outrage" - this may be a euphemism for rape - against her, but she escaped when her husband, Wilbur, their two children, and a black worker named Louis Swift returned from the fields to the house.

My great-great grandfather was taken to the cellar to await the sheriff. Word of the confrontation spread. Neighbors came to the house and took him away. He was found hanging from a tree the next day.

The Feliciana Sentinel concluded, "Of his crime there is no manner of doubt, of his fate, we have only to say, 'served him right.' With our confreres of the Clarion, and in fact most of our State exchanges, we feel that in such cases there is but one course to be pursued, no matter whether the guilty wretch be black or white."

My granddad's response: "That wasn't what we were told." Excited, he called my cousins about what I'd found and handed out copies of the article.

I combed as many records as I could find to discover more about what happened. Of course, no arrests were made, no trial was held, no one was convicted of Charles Brown's murder. I don't know who his parents were, where he grew up, or whether he was enslaved.

Curiously, I have the same question about my great-great grandfather as Northrup's descendants do of their ancestor. At the end of 12 Years a Slave, Northrup concludes, "I hope hence forward to lead an upright, though lowly, life. And rest at last in a churchyard where my father sleeps." His last known sighting was in 1857.

Adams told the Al-Jazeera network in an interview that for 15 years the family has tried to find out what happened to him. "His last request . . . hopefully, this movie will shed some light as to where he is now. . .. And if we can figure out where he is, [we can] transfer his body back to Baker's Cemetery so that his final wish could come true," he said.

Like them, we don't know where our ancestor is buried. My cousin scoured cemeteries throughout East Feliciana Parish, but couldn't find him. I've met only a fraction of my cousins, the descendants of his eight children.

Like Clayton Adams, I keep searching.