Logan Act was named for Philadelphia Quaker

By Chris Lombardi It's been more than a week since 47 Senate Republicans sent that letter to Tehran, and commentators can't get enough of asking: What about the Logan Act?

By Chris Lombardi

It's been more than a week since 47 Senate Republicans sent that letter to Tehran, and commentators can't get enough of asking: What about the Logan Act?

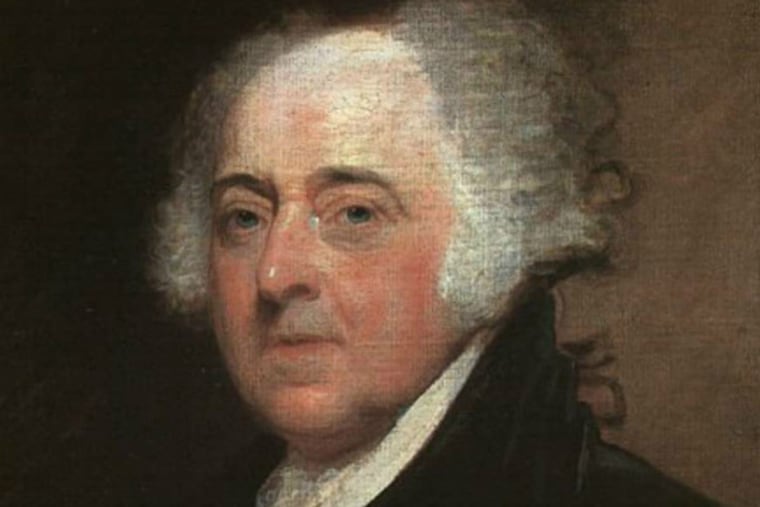

The law, passed by Congress and signed by President John Adams in 1799, prohibits unauthorized people from negotiating with foreign governments. Violating the act is a felony, and anyone convicted under the statute faces a three-year prison sentence.

Since news of the letter broke, more than 200,000 people have signed a petition urging that the 47 senators be prosecuted under the act. The law applies, some believe, because by sending an open letter to Iran's leaders, the signers directly disparaged the nuclear agreement being negotiated by the State Department.

Legal experts are often quick to explain that, since the passage of the act in the 18th century, no one has been prosecuted under it. But here's something they don't often mention: The bill's namesake was from Philadelphia.

The name Logan rings a bell with most Philadelphians, even if it's just from the name's ubiquity in town. "Logan? Like Logan Square?" But the act itself also has very Philadelphian origins: George Logan, a grandson of William Penn's secretary and later the U.S. senator from Pennsylvania, was a Quaker from one of Philadelphia's oldest families.

The Founding Fathers knew him well. Dr. Benjamin Rush described Logan as "the early, the upright, and the uniform friend of his country." Thomas Jefferson commended his "irreproachable conduct, and true civism," and John Dickinson spoke of his "love of country, candor of spirit, and boundless benevolence."

During what was known as the Quasi-War between the United States and France in the late 1790s, Logan spent weeks in Paris undertaking that most Quaker of pursuits: listening to French officials and trying to stop naval Kabuki from bursting into all-out war.

I first came across Logan's story while researching my book-in-progress I Ain't Marching Anymore: Soldiers Who Dissent, from Bunker Hill to Bowe Bergdahl. Logan's activism felt of a piece with the seething energy of the early republic, whose citizens sought to flex their muscles at every opportunity. It also felt emblematic of Philadelphia then, when someone like Logan could go beyond a life of pioneering new agricultural methods. Meddling in national diplomacy felt like good citizenship, especially when one considers his lifelong opposition to war.

Logan, who grew up at his family's ample Stenton estate, had spent the years of the American Revolution at medical school in Europe - returning to hobnob with Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, join the local militia as a medic, and begin serving in the Pennsylvania legislature. Fluent in French and something of early enthusiast of the French Revolution, he became uneasy when the first of America's wars for unclear purposes - the Quasi-War - came along.

Logan watched closely as Adams responded to naval maneuvers by the French, who had been made uneasy by unresolved treaty obligations and a new U.S.-Britain pact. Soon, the president was securing increased funds for a U.S. Navy and recalling George Washington in preparation for a ground war.

Disturbed by raging anti-French sentiment in Congress, Logan decided to travel to France, hoping to test the waters for peace with the Directory (the post-Revolutionary council). Once there, he proceeded to do what Quakers do best: He listened. When he came home, he talked about what he had heard - and this perhaps is why historian Edward Channing said Logan did "materially" shift the tide of American public opinion from war to peace.

But while he was gone, Congress had passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which, among other things, made it a crime to criticize the president. And because so many members of Congress regarded Logan's freelance diplomacy as traitorous, the Logan Amendment was attached to the law.

Logan didn't return home empty-handed. He had secured the release of some captured U.S. sailors and carried a list of possible terms for peace negotiators. However, when he arrived in November 1798, he was immediately, if briefly, arrested. He was never prosecuted - not then and not even a few years later, when he tried to keep the peace with England before the War of 1812.

Today, citing the Logan Act against the 47 GOP senators seems appropriate: Legislation meant to stop an enthusiastic Quaker from preventing a war could be used to block a move that could interfere with a peace treaty on Iran's nuclear program. I think Logan would approve.