Why 'apartheid schools' have become common in Philly and NJ | Editorial

The number of minority students attending 'apartheid schools' in New Jersey, where 1 percent or less of the students are white, has nearly doubled since 1989.

More than 60 years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, segregated schools persist across America. They can be found in largely white rural and suburban towns, in minority-majority cities like Philadelphia, and in supposedly progressive, ethnically diverse states like New Jersey, where what a new study calls "apartheid schools" have become common.

Apartheid, the legal term for the system of segregation that once existed in South Africa, was used by the UCLA Civil Rights Project to describe schools in which less than 1 percent of the students are white.

More than a quarter of New Jersey's black students attend apartheid schools, said the report, released last Wednesday. That ranks it sixth among states with the highest segregation of black students and seventh in segregation of Latinos.

The number of minority students attending apartheid schools in New Jersey has nearly doubled since 1989, from 4.8 percent to 8.3 percent; the number attending "intensely segregated" schools, in which less than 10 percent of the students are white, has risen from 11.4 percent to 20.1 percent.

Nearly half of all of New Jersey's black students and 40 percent of its Latino students attend "intensely segregated" schools. Meanwhile, the proportion of white student enrollment at private schools in New Jersey has reached 70 percent and is climbing.

Studies since the 1950s have consistently shown that segregated schools largely serving minority students tend to produce weaker academic results, which limit students' opportunities to succeed later in life.

That's not because the students are black or brown. It's because apartheid schools typically are found in impoverished communities with limited resources to spend on public education.

The number of New Jersey students living in poverty has increased by 10 percent since 1989, said the UCLA report. Eighty percent of New Jersey students attending apartheid schools and 77 percent of those in intensely segregated schools are poor.

There's no easy answer to ending apartheid to get those students an equitable education. Not only do their schools lack diversity, so do their school districts. The UCLA report said 75 percent of New Jersey public schools have student populations that are proportional to the racial composition of their districts. That means any significant demographic change must involve cooperation between neighboring districts.

New Jersey has the 11th largest student enrollment in the nation, 1.3 million children attending 2,518 schools in 590 school districts. Busing in the 1960s showed you can't force integration. The exodus of families to the suburbs was one result. But cooperating districts can work together to put more students in diverse settings that enhance their education.

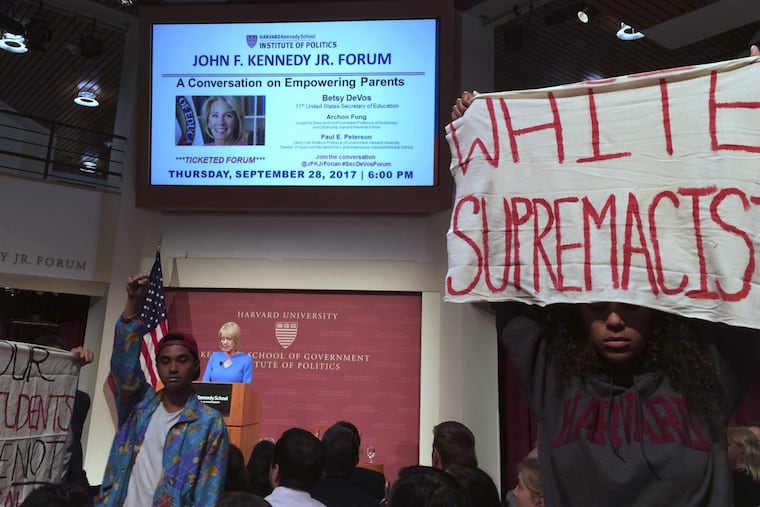

The Center for American Progress has suggested steps that would help. Unfortunately, several would require cooperation by the U.S. Department of Education, whose boss, Betsy DeVos, seems more inclined to undermine public schools.

But states like New Jersey could encourage diversity by providing additional funding to districts that agree to enroll students from outside their region, create regional charter schools that cross district lines, and redraw attendance zone boundaries so "neighborhood" schools pull from a more economically diverse student population. In each case, families must be involved at every level to ensure their voluntary participation.

It's time to end school segregation.