For former Eagle Norm Bulaich, history of concussions a worry

Another story in an occasional series on concussions. The CBS broadcasters for that Giants-Eagles game on Oct. 13, 1974, were intrigued by Norm Bulaich's unusual headgear. And once they caught sight of it, many in the Veterans Stadium crowd of 64,801 snickered into their Schmidt's.

Another story in an occasional series on concussions.

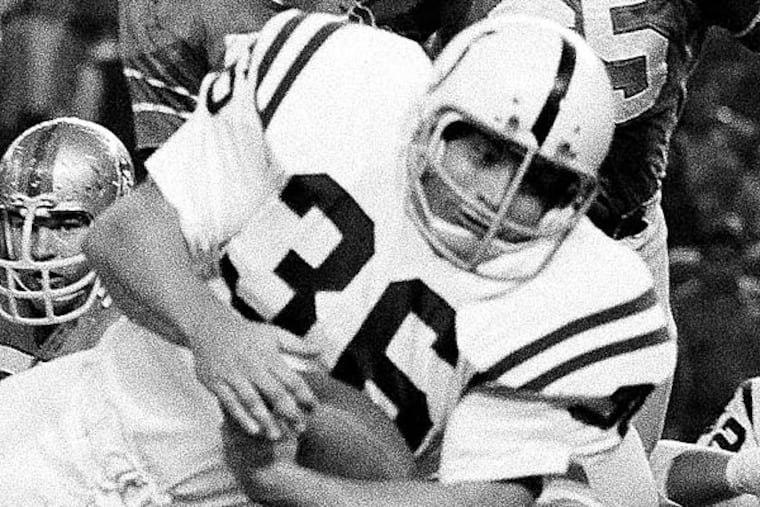

The CBS broadcasters for that Giants-Eagles game on Oct. 13, 1974, were intrigued by Norm Bulaich's unusual headgear. And once they caught sight of it, many in the Veterans Stadium crowd of 64,801 snickered into their Schmidt's.

A thick piece of foam rubber protruded like an ugly goiter from the rear of the Eagles fullback's green helmet.

"It looked weird," Bulaich recalled Thursday.

Actually, that rudimentary device was a peek into the NFL's future.

Bulaich's pad was one of the NFL's first visible attempts to combat concussions, a health issue that 38 years later is drawing increasing attention. And his story is typical of so many from that era.

Acquired in a trade with the Baltimore Colts before the 1973 season, the Texas Christian graduate had suffered a concussion in the 1974 season-opening loss to the St. Louis Cardinals.

" 'Boo' was knocked unconscious," Eagles coach Mike McCormack told reporters. "He was stunned and suffered a temporary memory loss."

When the same thing happened the next two Sundays - on hits McCormack conceded "weren't that hard" - the Eagles began to worry. They sent Bulaich to Duke University Hospital in North Carolina.

"I kept on getting pain going into my neck," Bulaich said in a telephone interview from his home in Hurst, Texas. "But, basically, I felt fine. The doctor at Duke said a concussion was like a bruise. If you don't rest it, you'll keep hurting the bruise."

He didn't accompany the Eagles to San Diego for their Oct. 6 game with the Chargers. The next week, Eagles trainer Otho Davis concocted the funny-looking helmet pad and Bulaich was cleared to play, carrying the ball just twice in a 35-7 rout of the Giants.

"Davis put the padding on the ridge around the outside of the helmet," Bulaich said. "He just thought maybe it would help. Most of the times when guys get concussions, it's when their head is going backward. But I really don't know if it helped or not."

Limited by the concussions and other ailments, Bulaich carried the ball only half as often as he had in his first Eagles season, when he'd collected 436 yards on 106 rushes. He totaled just 151 yards as the 1974 Eagles, despite a 4-1 start, finished 7-7. At season's end, he was dealt to the Miami Dolphins, with whom he finished his career in 1979.

In an NFL era when concussions were as commonplace as colds, Bulaich had to be among the league leaders. The hard-nosed, headfirst runner incurred so many "dings" that Eagles teammate Kent Kramer called him "Paper Head."

"I remember coming off the field and being somewhat out of touch lots of times," said Bulaich, who turns 66 on Christmas Day. "You'd get these stars shooting out. That happened throughout my career. But you were fine. You just played."

On the final play of his NFL career, when he was a Dolphin, Bulaich was hit in the head and knocked cold, suffering 12 broken facial bones. His head had been sandwiched between a pair of Green Bay Packers helmets.

"I crushed my face," he said. "I was out, like, five minutes on the field. The surgery was three hours. I walked away from it after that. That was enough."

Now the Texas native, who works with a waste-management firm, wonders about the damage that might have been done.

He underwent a brain scan in 2011 as part of a concussion-related study of former players and had another three months ago.

"After that first one, the doctor brought me in and showed me all these white dots on my brain scan," Bulaich said. "I'm not sure how many there were, but there were double digits. He said they were probably concussions I'd had. He told me I was OK for now."

Bulaich occasionally experiences moments of forgetfulness but isn't sure whether that's a normal part of his aging or early signs of something more serious and sinister.

"I get upset with myself when I go somewhere and can't remember why," he said. "Or when different things happen when I'm working. Unfortunately, we didn't make a lot of money then, so I'm still working in my old age.

"Maybe it's aging, but part of it's probably also the trauma my brain has taken. I am concerned. They can't reach out and say, 'Well, you're going to have Alzheimer's in five years.' But I'm assuming the trauma has taken a toll.

"I still haven't heard the results of that second test," he said. "Maybe I ought to call over there."