Kevin Turner's losing battle

The Ex-Eagle is still witty, can still walk & has his family back, but his disease has his children crying to sleep.

THE HARDEST part, of course, has to do with the kids.

They know their daddy once was a granite block of a player, a man whose strength of character matched his formidable strength of body.

The character remains.

Kevin Turner walks without much problem; slimmer now, he strode into the huge downtown restaurant erect to attend the Bert Bell Memorial Award Dinner with a smooth step that recalled his five seasons as the Eagles' fullback. His mind is sharp.

The ALS has taken everything else.

His neck cannot support the weight of his head. His vocal cords and facial muscles are failing, so speech has become a maddening labor. His arms hang, slack; his hands are useless, his fingers immobile, as if carved. Tying his shoes, feeding himself, cleaning himself - these things have been beyond him for years.

Turner is 44.

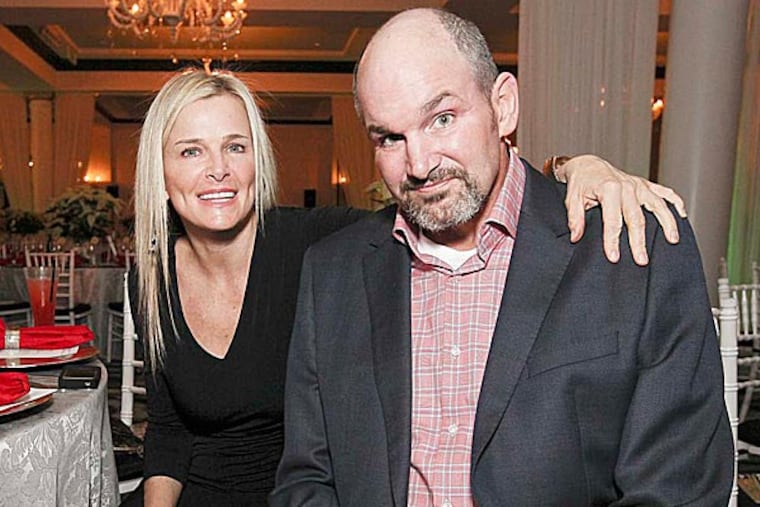

He divorced his wife, Joyce, in June of 2009, just after the ALS diagnosis, and moved 10 miles down the road. They rekindled the romance. Just 3 weeks ago he moved back into the house in Birmingham, Ala., where she lives with his two sons and daughter. Their divorce was independent of his condition, and their reconciliation is real. They enter the restaurant last night, and Kevin admits he is hungry.

Joyce picks a morsel off a passing tray. She holds the spring roll to his mouth; his teeth nip off a piece. She holds a Coke to his mouth; he sips through a straw. She wipes the corner of his mouth.

"I'd trade with him in a minute," Joyce says. "Just watching him go through it.

"But the worst part?"

She pauses, cocks her head, and resumes:

"It's hearing my children cry themselves to sleep."

This summer Turner was part of a $765 million settlement of a suit between the NFL and a group of former players that addressed the league's role in allowing players to continue to play after suffering various degrees of head trauma. Turner is in line to receive as much as $5 million.

Well, his family is, anyway. Turner, 44, knows he might not live to see the day.

"I ain't got a dime, yet," Turner says, with a chuckle. He is anything but maudlin.

Turner recognizes criticisms that the plaintiffs settled for too little, that the owners' pockets won't hardly be lightened; he is not a critic.

"A lot of players seem upset with the amount of money," Turner says. "I'm happy about it."

He's happy because he saw it through. His Kevin Turner Foundation perpetually raises funds to fight ALS and raises awareness about the disease, which helped him earn the Jim Johnson Courage Award, but only recently has ALS been recognized as one of the conditions that can result from the pounding of practices, of training camps, of games.

"I probably did more damage in practice and in training camps than I did in 106 games," Turner says. "That's the part we can fix."

That part was fixed, a little, in 2011, when the new collective bargaining agreement reduced the amount of contact players could be subjected to in practice; the Eagles, under Chip Kelly, hardly ever hit. And, of course, the rules have been changed to alter the types of blows that can be leveled in games.

Then again, Turner often initiated the contact.

When offensive coordinator Jon Gruden was replaced by Dana Bible in 1998, Turner began to think his career was pointless.

"That 1998 season was a joke. The whole year was a waste of time. Bible is a good man, but he was in about 10 feet over his head," Turner says. "I remember driving home with Bobby Hoying after the season opener in 1998 [a 38-0 loss to Ricky Watters and the Seahawks]. That was the only game I'd played where I went in thinking we'd just get our [butt] beat. I asked Bobby, 'What do you think of the plan?' He didn't say anything. We just looked at each other. And we laughed.

"There wasn't any plan."

The plan, in the NFL, always is: Get the most out of these magnificent athletes until their bodies crumble. In Turner's day, little thought was given to their minds.

That was chillingly played out with Turner a year before in 1997. He was knocked for a loop on the opening kickoff. Still, he never missed a play. Then, midway through the second quarter, he discovered himself sitting on the sideline. He looked at Hoying.

"Bobby, I know we're playing the Packers," Turner said. "Are we in Philadelphia or Green Bay?"

Hoying called over the team doctors.

"They held me out maybe two series, until after halftime," Turner said. "I played the second half."

He played the rest of the season, too. That was then.

Eagles nickel corner Brandon Boykin left Sunday's loss in Minneapolis with a head injury. He is undergoing the league-mandated concussion protocol, according to general manager Howie Roseman.

Asked when Boykin should come back, Turner did not hesitate:

"I saw the game. I saw the play. At least 2 weeks."

Turner never got 2 weeks off. Not if he could walk.

Turner underwent back and shoulder surgeries after 1997. He was the king of the "stinger," a neck-nerve injury that often numbs an arm. Turner had played with a double hernia, knee tendinitis and a broken heart; he took a 30 percent pay cut in 1999, when Andy Reid replaced Ray Rhodes. The restructuring kept Turner from being cut, but it also erased the final year of his deal. The stingers became chronic in 1999. He could not finish that season, and never played again.

"I was so angry when they gave him the pay cut. It was just the principle. The stingers, the pay cut . . . I was just finished," Joyce says.

Turner mulls the question, though, clearly, he has considered it before.

If you knew your brain would take such a beating, would you have played in the NFL?

"At that point, you're 22 years old, you're in the best shape of your life, you think you can run through a brick wall," Turner begins.

And, so, you try? Again? And again?

"If I knew then I might end up this way, I think I still would have played," Turner says. "But I would have practiced differently. I'd have been quicker to come out of games. And I'd have retired after that 1997 season, when I got that big hit."

Maybe he would have. The only problem is, Turner still adores the game. Absolutely loves it. He loves Chip Kelly's mad genius, but marvels at its implementation.

"I can't imagine what kind of shape they must be in," Turner said. "I needed the huddle."

Turner loves the recent domination by his alma mater, Alabama. He even loves the thought of his sons feeling the warmth of a football team's camaraderie and the thrill of bettering the man across from him.

Will he deny his gifted boys a shot at eight NFL seasons like their daddy? Can he?

Nolan, a 16-year-old sophomore at Vestavia Hills, played nickel corner and safety on the 6A semifinalist.

"Ah, safeties, you know, they just run after the guy," Kevin tells Joyce.

Nolan also returns punts. In that case, 11 guys are running after him. Kevin does not explain this to Joyce.

Nolan will be out of high school when Cole, 10, gets his turn.

"I'll let him play when he gets to the eighth grade," Turner says. "He's mad at me. But I did some research, and I learned, and I believe, the brain grows and changes so much until you're 14."

Kevin Turner began playing when he was 5.

Then again, you can't keep them in a bubble.

A couple of weeks ago Cole was playing in a recreation league basketball game. He's good, like his brother, and he's a hustler, like his dad.

Midway through the second quarter Cole dived for a loose ball. He bonked heads with another kid. Cole got up, apparently none the worse for wear.

Kevin rose from his seat, his arms rigid at his sides, and walked down to the court.

He made the coach take Cole out of the game.

On Twitter: @inkstainedretch

Blog: ph.ly/DNL