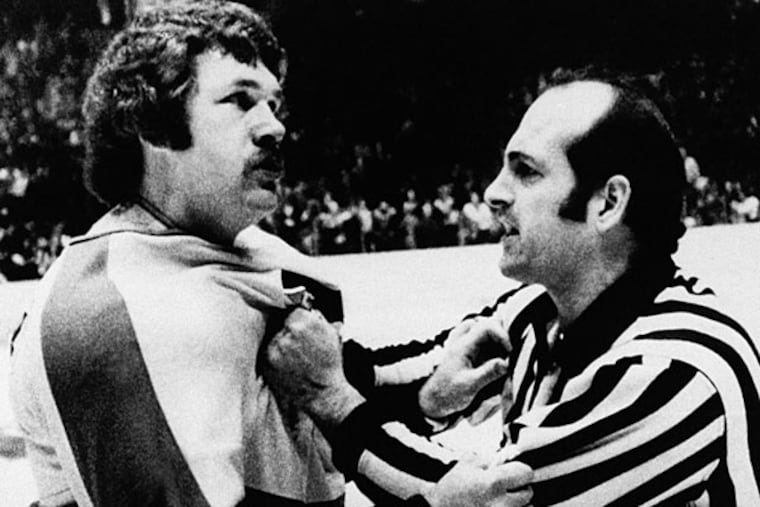

Schultz vs. Rolfe: Fight resonates 40 years later

Dale Rolfe doesn't think much about his role as the victim in the most famous fight in Flyers history. He hasn't watched a hockey game in 35 years, he said, and doesn't care either to watch another one or to recall those he played. OK, that's an exaggerat

Dale Rolfe doesn't think much about his role as the victim in the most famous fight in Flyers history. He hasn't watched a hockey game in 35 years, he said, and doesn't care either to watch another one or to recall those he played. OK, that's an exaggeration. He does catch an NHL playoff game on TV once in a while, but he'll turn 74 next week, and he'd rather spend another summer in Panama City Beach, Fla., or another winter morning hunting moose and deer near his Gravenhurst, Ontario, home. The day that Dave Schultz beat him up doesn't interest him as a discussion topic, if it ever did.

"That's history," Rolfe said in a recent phone interview. "Nobody cares about that anymore."

Perhaps he's just too far removed from the rivalry to understand how wrong he is. The Flyers and the Rangers are preparing for Friday's Game 4 in this first-round playoff series, and Rolfe's fight with Schultz remains a flash point between the two franchises 40 years after it happened.

Before every game in this series, both at Madison Square Garden and the Wells Fargo Center, the home team has run a highlight video on its arena Jumbotron. The videos are catered to their respective fan bases - pro-Rangers at MSG and all-orange-and-black at the Center - but they do share one striking similarity: Instead of showing any of the seven goals in the Flyers' 4-3 victory in Game 7 of the NHL semifinals on May 5, 1974, each video shows the Schultz-Rolfe fight.

Once more, there's that scrum near the Rangers' net in the first period; those two quick punches from the 6-foot-4, 210-pound Rolfe; and that rainstorm of right hands from the 6-foot-1, 190-pound Schultz - 18 of them in succession, snapping Rolfe's head backward like the top of a Pez dispenser, the taller, heavier man too dazed and wobbly to respond - until Schultz grabs Rolfe by the hair and head-butts him.

"That was a little embarrassing," Schultz said. "But you were allowed to do that back then."

In New York, the fight is regarded with a kind of refined distaste - as much refinement as hockey allows, anyway. The reason the Rangers included it in their pregame video is the mentality it feeds.

Can you believe the barbarity those Philadelphia heathens had to sink to just to win? Come on, Rangers fans. Let's kick their butts.

Conversely, Schultz's 45 seconds of fury captured the Flyers' ethos, from then until now. They've long based their philosophy for winning on the belief that they can inspire their players and intimidate opponents by treading on the dark side of their sport.

It's the thread that connects their 1974 and '75 Stanley Cup teams to their infamous pregame brawl in Montreal during the 1987 playoffs to Ray Emery's November decision to chase down and pummel Capitals goaltender Braden Holtby to Jake Voracek's Game 3 throw-down with Carl Hagelin.

Always, no matter how many years pass without another championship, the justification for sticking with this approach is convenient enough to manufacture: The Flyers couldn't have beaten the Boston Bruins in the '74 Finals without winning Game 7 against the Rangers first, and they might not have beaten the Rangers had Schultz not pounded Rolfe.

"There was no way we were going to lose the game after seeing how dominant Davy was in the fight," said former Flyers forward Bill Clement, who was injured and watched it from the Spectrum's press box.

"Whether it won the game or not, it was reinforcing why we were so dominant at home. The crowd was insane," Clement said. "The Rangers were a proud franchise, but it reinforced the idea that there were a lot of guys who came to play the Broad Street Bullies who didn't want to play there. We had a feeling of invincibility."

The optics of that moment, that apparent play on the hearts and minds of the Rangers, remain powerful enough that Schultz said Flyers fans still approach him about it. That none of Rolfe's teammates jumped in to help him has always been held against the Rangers, as though they were too terrified of Schultz to defend Rolfe - a suggestion that Schultz considers an unfair myth.

"It was Game 7," he said. "Who wants to get ejected?"

So Rolfe took the beating alone, and though it was the most memorable sequence of that series, it wasn't his most consequential.

A week earlier, in Game 4, he fired a slap shot that struck Flyers defenseman Barry Ashbee in the right eye, ending Ashbee's career. The two of them had been junior-hockey teammates and roommates in the mid-1950s with the Barrie (Ontario) Flyers, and unlike the Schultz fight, the memory of his friend lying in the Madison Square Garden trainer's room hasn't been so easy for Rolfe to shake.

"You could tell it was bad," he said.

The following season, 1974-75, was Rolfe's eighth and last in the NHL. After he retired, he owned and operated a plumbing company that he sold some years ago.

Anyone who talks about the Schultz fight these days "has too much time on his hands," Rolfe said, and if it was such a touchstone event for the Flyers, "they should have invited me down for some games."

They'd better send the invitation soon. It was 78 and sunny in Panama City Beach on Thursday, and moose season in Ontario begins on Sept. 20.