Veteran soccer executive Kevin Payne reflects on the state of U.S. soccer

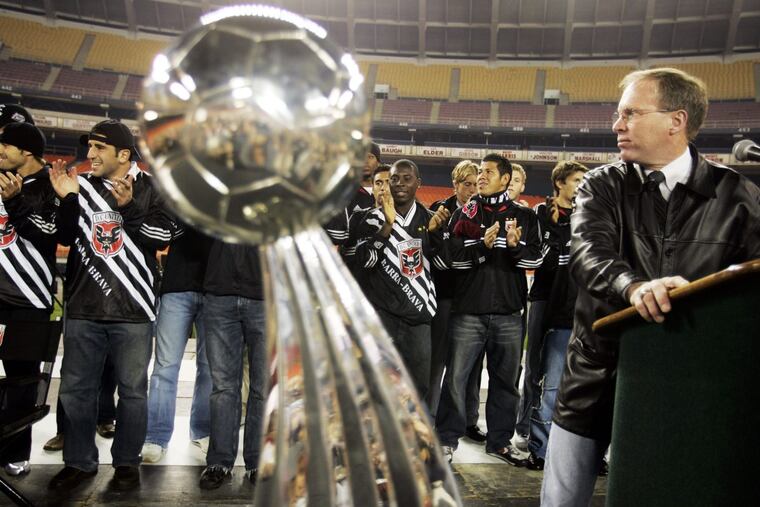

Kevin Payne is a former president of D.C. United and member of U.S. Soccer Federation's board of directors. He now runs one of the nation's largest organizers of youth and adult amateur leagues.

U.S. Club Soccer CEO Kevin Payne recently spoke to the Inquirer and Daily News in a long interview. Payne is a former president of D.C. United and was on U.S. Soccer Federation's board of directors from 1999 to 2014. He now runs one of the nation's largest organizers of youth and adult amateur leagues.

The interview covered so much ground that it made sense to split the transcript into a few parts. The first, published here, is about the current state of the American soccer landscape in the wake of the U.S. men's national team's failure to qualify for the 2018 World Cup.

Part 2: The difficulty in getting rid of the pay-to-play culture in American youth soccer

Part 3: The high cost of coaching in America, and his view on the upcoming U.S. Soccer Federation presidential election

The transcript has been edited lightly for clarity.

On the state of the American soccer landscape in the wake of the U.S. men's national team's failure to qualify for the 2018 World Cup:

First of all, I think that we need to be careful that we don't try to draw broad conclusions from some fairly narrow outcomes. I pointed out to somebody recently that within a manner of a day or two from us losing in Trinidad and missing out on the World Cup, our under-17 team beat Paraguay in the knockout round of their World Cup 5-0. The comment I made was, "Not everything is wrong because we failed to qualify for the World Cup, and not everything is right because we had a very good result at the U-17 level."

I think that one of the problems we've had in U.S. soccer over the years is that we have tended to think that there's some magic answer, and there's some specific thing that if we do that, we will get different results. I've spent a lot of time and a lot of years talking to people who are in the business of developing players in a lot of different countries — Argentina, Brazil, Holland, Spain, France. And what you find is that there are a lot of very common elements.

The most common element is that they do a lot of things the same, and they do them consistently. I think the biggest thing that they share in common that is different from the way we approach the youth soccer world is that in most of those countries, youth soccer coaches see their job as trying to improve players.

I think here, too often youth soccer coaches think their job is to win youth soccer games. That produces a very different mindset on the part of a coach. The coach who thinks that he's supposed to win matches is going to be focused on whatever he needs to do to accomplish that. At the youth soccer level, that often [results in] really not playing very good soccer. Relying on the disparity in physical development between players, and so forth.

So I think that the first thing we need to do is do a better job of identifying what it is we want from our youth soccer coaches. And when I say "we," some of that can be directed by U.S. Soccer or MLS clubs or an organization like mine, but really, who we have to convince is parents. They pay the freight. They are the ones who determine whether coaches are doing the job they want them to do or not.

And I think most parents don't really know what they want. They have some vague idea that they want their kid to get into college, but they don't really know how best to accomplish that. Something that we need to do, and that U.S. Soccer needs to do, is to try to engage in a broader and more consistent and comprehensive dialogue with parents about how they should make decisions about their child's soccer experiences.

We've begun doing that at U.S. Club Soccer with our Players First program. But I think it's safe to say we're the only ones who are attempting to address this in a comprehensive way. So I think that's, in my opinion, the starting point. We need to have a better understanding of what it is that we want our youth soccer coaches to do.

On how to best get the message through to youth soccer coaches that they should not have results as their first priority:

Honestly, I don't think it's fair to blame the coaches. I think most coaches understand what they should be doing, and they also understand what they are doing, and they understand that those two things are not always the same.

But you have to remember that the vast majority of coaches in this country are making their living through coaching these kids, and they have to be answerable to the people that pay the bills — and right now, that is parents.

In a country like Argentina, let's say, if you're a youth development coach at San Lorenzo, you're coaching the 15-and-under team, you do what your bosses tell you to do. And in their case, your job is to try to help identify and groom players for the first team, or to sell. Nobody particularly cares if you win your youth soccer games that weekend.

We don't have the same system in this country. Obviously, there's a relatively small number, on a percentage basis, of professional clubs that have academies. And to varying degrees, they are committed to trying to develop players. In some cases, I believe all they've done is transplant youth soccer coaches into their academy systems who still act as though it's the same systems that they grew up in.

One thing I want to be clear on: I'm not questioning or denigrating the pay-for-play model. I think that's become a really easy buzzword for a lot of people who don't spend real time thinking about this process.

Somebody pays for kids to play everywhere, other than kids playing in the park. If there's a coach involved, if there's regular training involved, if there's uniforms and so forth involved, somebody's paying for that. So in a country like Germany, if a kid is playing at Bayern Munich, the team is paying for that.

But in a country the size of ours, it's difficult to funnel everybody through a system in which a professional club is footing all or most of the bill. We also have kind of a confusing element in college soccer. Really, the biggest beneficiary in terms of player development from youth soccer in America is the college game. There's many, many more opportunities to go to college each year than there are professional opportunities for players.