Philly is about to triple the number of languages it supports in elections

The new proposal adds support for Russian, Vietnamese, Khmer, Arabic, Haitian Creole, and Portuguese.

Your vote is your voice. But what if you don’t speak English?

Voters and would-be voters with limited English proficiency can struggle to cast ballots when information about elections isn’t available in their languages. Philadelphia has tens of thousands of eligible voters, across multiple communities, who are limited in their use of English. Federal law has long required the city to provide election materials in Spanish in addition to English. Starting this year, Philadelphia is also required to translate everything into Chinese.

Now the city is about to undertake a significant expansion of that language access: On Wednesday, Philadelphia elections officials voted to triple the number of languages the city supports.

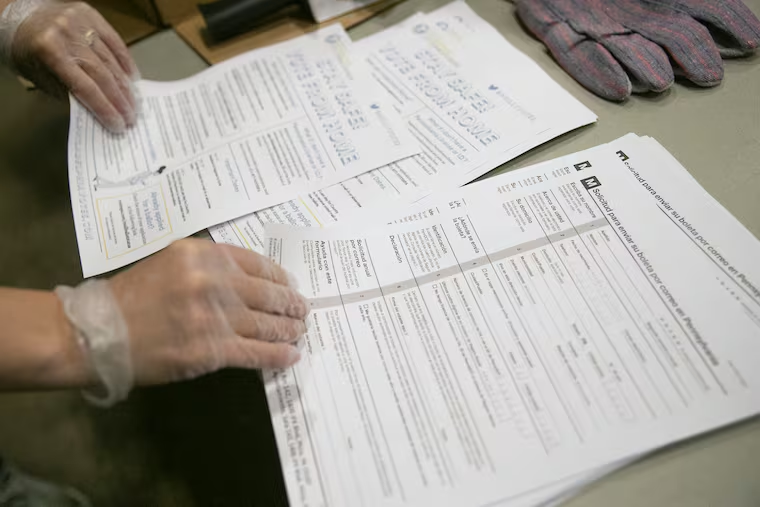

The plan won’t add languages to voting machines and mail ballots, but will translate other election materials like voter guides, polling place signs, and ballot questions.

“This is exciting,” said Al-Sharif Nassef, the Pennsylvania campaign manager for the nonpartisan advocacy group All Voting Is Local. “This proposal is a good first step toward full language access for the voters of Philadelphia who speak a primary language other than English.”

A coalition of community groups and advocacy organizations, under the banner Citizens for Language Access, has pushed for expanded language support for several years. Nassef and other leaders of that effort hailed the new proposal as a major step for inclusion — while promising they would continue to press for more.

Seth Bluestein, the sole Republican on Philadelphia’s elections board, introduced the proposal at the city commissioners’ meeting Wednesday morning. The two other commissioners, both Democrats, voted for the plan.

“What I want people to take away from this motion is that these voters matter, their votes matter,” Bluestein said, “and that we’re going to do everything in our power to make sure that eligible Philadelphians are able to register, and registered voters are able to vote.”

What Philadelphia’s new language-access expansion does and doesn’t do

Section 203 of the federal Voting Rights Act sets thresholds for when elections administrators must provide materials and information in a language other than English.

That’s why Philadelphia had bilingual ballots and materials in English and Spanish; this year, it added Chinese after the Census Bureau found that community had met the Voting Rights Act standards.

The new plan adds support for Russian, Vietnamese, Khmer, Arabic, Haitian Creole, and Portuguese.

The plan will translate elections materials, including voter guides and other outreach materials; polling place signs; and ballot questions. It also creates an advisory committee that would meet four times a year beginning next year.

Support for future languages would be determined by Census Bureau data.

The plan would also require a report after each election that breaks down how often each language was used in each precinct to vote by mail, vote on voting machines, and submit voter registrations.

Some of the translation work, such as the polling place materials, can be done quickly and should be available in November’s election, Bluestein said. The rest of the plan is to be completed by next year’s May primary.

The plan does not add languages to the actual ballots and voting machines.

And because the applications for voter registration and mail ballot requests come from the Pennsylvania Department of State, those won’t be immediately translated, either.

Why the plan matters

Not everyone speaks English, and the United States has no official language.

But for some communities, not speaking and reading English can be a barrier to engaging with government, including elections.

“Through some of the work we’ve been doing through the years trying to get people engaged in our democracy and voting, we see that language can be a hindrance to being a full participant,” said Andy Toy, who helped lead the language access coalition.

Voting power translates into representation — elected officials value most the preferences of the voting blocs that can help them win their next election.

“If you know that more people are voting and actively engaged, you will probably want more of them in some kind of leadership roles,” Toy said. “So if you wanted to make this a more representative city, one of the steps is to have more people voting, of course, and one of the steps is to have more people in those other positions.”

The organizers hope the addition of the new languages can help between 42,000 and 85,000 voters.

Of course, the plan doesn’t itself solve all the voting challenges for people with limited English proficiency.

After all, many English-speaking voters sit out election after election. And while Spanish has been on the ballot for years, low-income Latino neighborhoods have some of the lowest turnout rates in the city. Chinese was added to the ballot in the May primary, and one-tenth of 1% of votes cast on the voting machines — 175 out of more than 166,000 — were cast in Chinese.

The advocates know that. They describe the effort as a starting point that, among other things, sends a message of inclusivity.

“Language access opens the doors for community leaders … to reach voters,” Nassef said. “It’s up to organizations to ramp up their organizing, it’s up to donors to enable and empower community organizations … and it’s sort of an all-hands-on-deck effort.”

It was a bumpy road to get here, and it’s not over yet

Language issues aren’t new.

So when Philadelphia bought new voting machines — which the commissioners touted as being able to accommodate more languages — community groups decided to organize more formally.

The advocates began by making a big pitch: Support more languages as fully as you do Spanish and Chinese, including translating the actual ballots and voting machines.

They were met with resistance. There are logistical challenges to doing that, officials told them, and it would be expensive.

“I thought we could make more progress, but it was pretty early on I realized it’s going to take a lot more,” said Lisa Deeley, the city elections chief, who has publicly supported an expansion of language access but has been seen as more resistant to the effort than other officials. “I thought when we selected our current voting system it would be easier, but it is still a big lift. … We’ll be in a better position to do it, to add more languages, in the future, but for right now, we’re happy to do this.”

Deeley said the challenges include unfunded mandates from the state and the volume of work that drew city elections officials’ attention and resources away from the language plans.

Advocates kept up the pressure and found allies on Philadelphia City Council, which controls funding. They also changed their proposal, in part because of the challenges in putting Chinese on the ballot. And the rise of mail voting has also changed the game, they said.

“We saw that a fair number of immigrant folks felt much more comfortable doing the mail-in ballot than going to the polling place. Polling places can be intimidating places for some people,” Toy said.

Still, they want the ballots and voting machines to support more languages, and all three commissioners said they’re on board with that.

The ultimate vision, advocates said, goes beyond access.

“The end goal is full inclusivity of language-minority communities in the democratic process,” Nassef said, “where not only the language is available but we really see very high levels of participation.”