Fact-checking the seventh Democratic primary debate

Here’s a roundup of eight claims from Tuesday’s Democratic presidential debate.

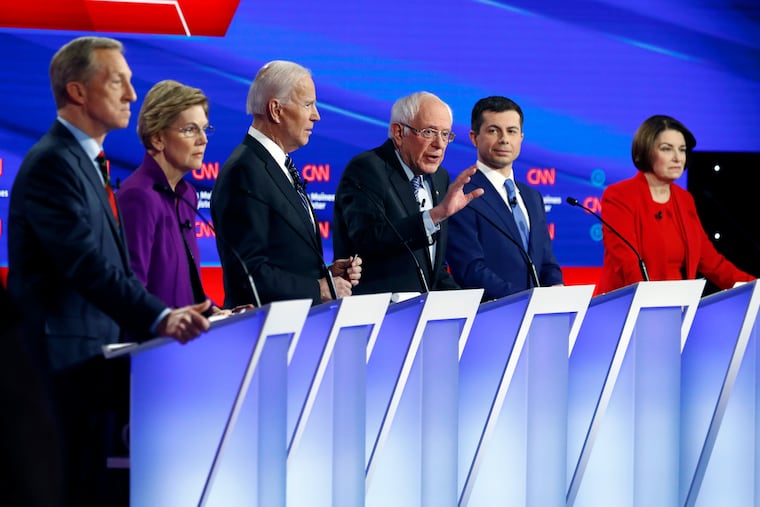

The seventh Democratic presidential debate of the 2020 campaign, hosted by CNN and the Des Moines Register, had six candidates, lasted little over two hours — and did not have many statements that merited fact-checking. Here are eight claims that caught our attention, mainly about the Iraq war and health care.

This version of history is disputed by former president George W. Bush.

“I’m sure it’s just an innocent mistake of memory, but that recollection is flat wrong,” Bush spokesman Freddy Ford told the Fact Checker. He included a link to a podcast titled “A Polite Word for Liar.”

Here’s what happened.

Biden, during the Senate debate on a resolution authorizing force against Iraq on Oct. 10, 2002, argued that the resolution was designed to ensure diplomacy. But he also fought against alternatives offered by more liberal Democrats that would have required Bush to first win U.N. authority for an invasion or else seek a new war resolution from Congress.

“The reason for my saying not two steps now is it strengthens his hand, in my view, to say to all the members of the Security Council: ‘I just want you to know, if you do not give me something strong, I am already authorized, if you fail to do that, to use force against this fellow,’ ” Biden argued on the Senate floor.

The U.N. ordered weapons inspectors back into Iraq, but the administration got impatient with the results, calling for the inspections to end almost as soon as they started. Irritating allies, the administration argued that the inspections could not be allowed to drag on because the U.S. military buildup in the Persian Gulf region had proceeded too far to turn back from war.

Nevertheless, Biden continued to express support for his vote. “I supported the resolution to go to war. I am not opposed to war to remove weapons of mass destruction from Iraq,” he said in a February 2003 speech. “I am not opposed to war to remove Saddam [Hussein] from those weapons if it comes to that.” But he added that Bush was not being straight with the American people about the possible financial and military burden.

Just before the start of the conflict began, in a Post opinion article, Biden unsuccessfully argued that an invasion should be delayed until the administration obtained a U.N. resolution authorizing an attack. That was the position taken by Senate liberals that Biden had previously dismissed during the debate about the war resolution.

Bush, in his book “Decision Points,” wrote: “Some members of Congress would later claim they were not voting to authorize war but only to continue diplomacy. They must not have read the resolution. Its language was unmistakable: ‘The President is authorized to use the Armed Forces of the United States as he determines to be necessary and appropriate in order to defend the national security of the United States against the continuing threat posed by Iraq; and enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq.’ ”

» READ MORE: Key takeaways from the seventh Democratic presidential debate

Biden voted for the Iraq War when he was a senator, and many Democrats won’t let him forget it.

On the campaign trail these days, Biden often says Americans can trust his judgment on questions of war because he was later in charge of a U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq during President Barack Obama’s first term.

In 2009, Obama asked Biden to manage the withdrawal of U.S. forces. Obama wanted “sustained, high-level focus” from the White House on that issue, “and then he turned to the vice president and said, ‘Joe, you know more about Iraq than anyone and I want you to take care of that,’” said Antony Blinken, who was Biden’s national security adviser in the White House and then deputy secretary of state from 2013 to 2015. Biden chaired a committee that made sensitive decisions about the pace and scope of the troop withdrawal, while also keeping an eye on economic and political issues in Iraq. The Biden committee included representatives from the Defense Department, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Treasury Department and other agencies.

But Biden often leaves out what happened after that. Obama sent U.S. troops back into Iraq in his second term. Biden was still the vice president.

The Biden camp argues that these are two different conflicts and that the troop levels were much higher pre-2011 and much lower post-2014. However, as top Obama administration officials have said in public, the two conflicts are inextricably linked. The Islamic State gained a foothold in Iraq in large part because U.S. forces had withdrawn.

We previously gave Two Pinocchios to Biden for telling half the story.

Buttigieg is correct here. Despite frequent claims, Trump did not express opposition to invasion of Iraq before it occurred. He even praised the invasion immediately afterward. Trump only became outspoken in his opposition in 2004. Trump earned Four Pinocchios for his claim.

Adjusted for inflation, Biden’s $42,500 salary as a senator in 1972 would be almost $260,000 in today’s dollars. Meanwhile, the average cost of child care in Delaware currently ranges from nearly $9,000 to $11,000 per year, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

That suggests Biden would have had the means to afford child care in his home state in the early 1970s, though we can’t be certain because other financial factors could have been at play.

It’s worth noting that in an emotional speech at Yale University in 2015, Biden said “the real reason I went home every night was that I needed my children more than they needed me.”

In this debate, Sanders did not define what he meant by the “status quo,” but in the third debate he said the cost of the “status quo” would be $50 billion over 10 years, compared with more than $30 billion for Medicare-for-all. When we queried the Sanders campaign during the debate for the source of the $50 trillion figure, we were directed to posts that were written by Paul Waldman for The Washington Post’s “The Plum Line,” an opinion column.

Waldman compared a government projection that national health spending would amount to about $50 trillion over the next decade to an estimate that projected the federal cost of Medicare-for-all as $32.6 trillion. In one column cited by the campaign, Waldman wrote: “So if Medicare-for-all actually costs $40 trillion, we would save $10 trillion. Hooray!”

Waldman told the Fact Checker he has not read academic studies that looked closely at the impact of a Medicare-for-all plan on national health expenditures. It turned out that all but one of five major studies, from the left to the right, predict the Sanders plan would increase health spending, not reduce it. The author of the fifth predicts a decline but said Sanders’s statement is exaggerated.

We ended up giving Sanders Three Pinocchios for his comment.

Sanders said this twice in the debate, but both times he did not quite get it right. He apparently meant to say that the United States spends twice as much as other developed countries — defined as members of the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Instead, he said twice as much as any other country.

United States pays far more than per capita on health care than any other major country in the world ($9,892 in 2016) — twice as much as Canada ($4,753). The OECD median was $4,033. But Switzerland is a major developed country, and U.S. costs are 25 percent higher than Switzerland ($7,919). These figures come from a study by a team led by a Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researcher.

More recent OECD estimates show the United States spent $10,586 per person, compared with Switzerland ($7,317 per person), Norway ($6,187 per person) and Germany ($5,986 per person). All of those are more than half of U.S. spending, though the OECD average was just under $4,000. So Sanders would have been correct if he spoke about the average or median of other developed countries.

Sanders often repeats this talking point, asserting that 500,000 people go bankrupt every year from medical bills. That’s approximately two-thirds of the 750,000 total bankruptcies per year.

We’ve previously given Three Pinocchios to Sanders for this claim, which he keeps repeating.

The claim is based on an editorial published by the American Journal of Public Health in March. The researchers surveyed debtors and asked about factors that contributed to their bankruptcies. Forty-four percent said either medical bills or loss of work related to illness “very much” contributed; 22 percent said either medical bills or illness “somewhat” contributed. Combining both groups of respondents, the study estimated 530,000 bankruptcies a year.

But the study doesn’t establish that all 530,000 bankruptcies were caused by medical bills. It’s broader because it measures medical bills and illness. It measures contributions, not causes, to bankruptcy. And it includes respondents who said medical bills or illness factored into their bankruptcy either “somewhat” or “very much.”

A different study published in the New England Journal of Medicine looked at the same question of medical bankruptcies and found that the rate was far lower: 30,000 to 50,000 a year. However, this study was limited to non-elderly people who were admitted to the hospital for non-birth-related reasons, so it covers only a subset of all people facing medical debt.

The research team Sanders cited once included Elizabeth Warren, who contributed to earlier versions of the study when she was a Harvard University professor. Interestingly, though, Warren never makes the same claim about 500,000 medical bankruptcies a year.

This is a favorite line of Sanders — he used it twice in the debate — but the way he frames it is exaggerated. His number came from a single-night survey done by the Department of Housing and Urban Development to measure the number of homeless people. For a single night in January 2018, the estimate was that 553,000 people are homeless.

But the report also says that two-thirds — nearly 360,000 — were in emergency shelters or transitional housing programs; the other 195,000 were “unsheltered” — i.e., on the street, as Sanders put it. The number has been trending down over the past decade. It was 650,000 in 2007.