Off the Jersey Shore, a vast deposit of fresh water lies beneath the ocean floor

The underground aquifer system is thought to cover an area of close to 15,000 square miles, nearly twice the size of New Jersey.

Decades ago, oil companies drilled exploratory wells off the Jersey Shore, yet did not find much of what they were looking for. But deep in the rock beneath the salty surf, they found hints of another precious resource: fresh water.

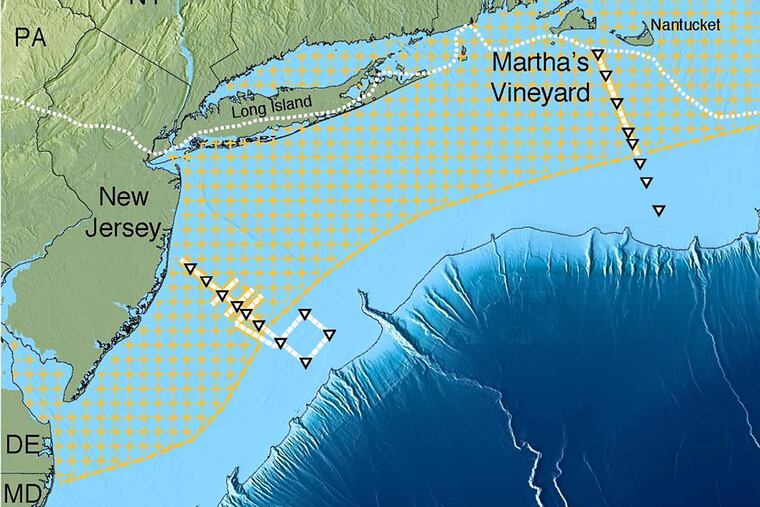

Using sophisticated electromagnetic sensors, a team of scientists has finally started to map the extent of this underground water, and they think it is enormous. In a study published this month, they said a freshwater aquifer system appears to extend more than 55 miles off the shore, likely reaching from New Jersey up to Martha’s Vineyard.

With an estimated volume well into the trillions of gallons, the water is probably not fresh enough to drink, but it is close. The concentration of salt in typical seawater is about 35 parts per thousand, while in earlier drilling samples, the salinity of the water beneath the ocean floor was found to be as low as 2 parts per thousand.

The new findings suggest some of the underground water may be even less salty than that, said lead author Chloe Gustafson, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Drinking water has a salinity below 1 part per thousand, so in theory, Jersey’s offshore resource would not require much treatment. (Just think of the marketing opportunities: Soprano Springs! Eau de Boardwalk!)

In all seriousness, there is little chance utility companies would train their sights on the deposits beneath the northeast Atlantic, as fresh water is relatively plentiful on land in the region. But evidence suggests that similar freshwater aquifers exist offshore throughout the world, and they may well be targeted for human use in areas where clean water is scarce.

The researchers said it was important to study these aquifers and determine where the fresh water came from, in order to determine the potential environmental impacts should companies ever propose to drill.

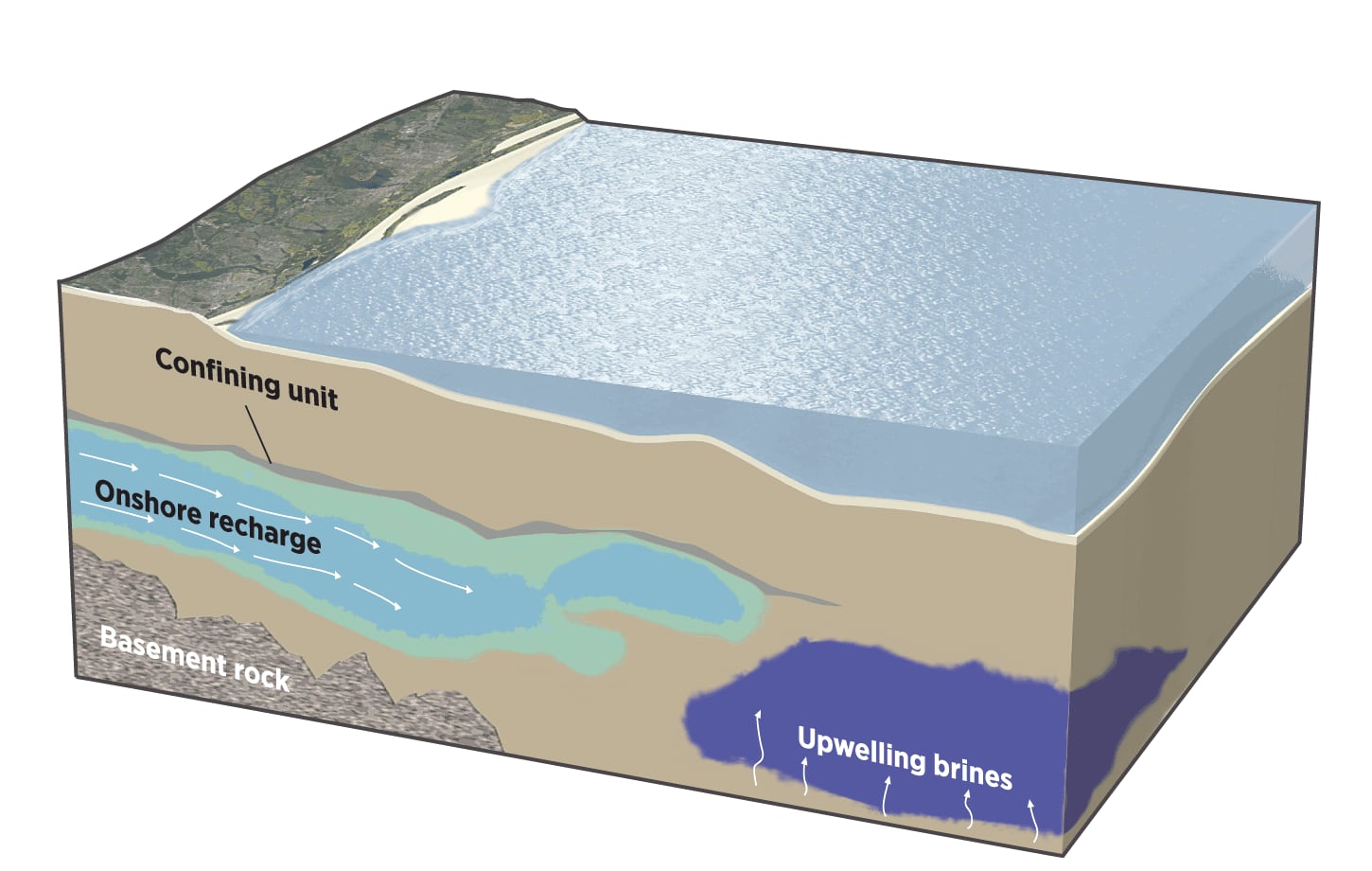

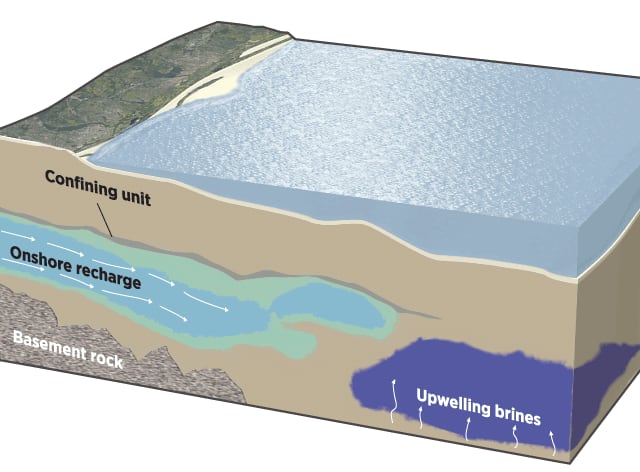

Some of these offshore water deposits are likely connected to underground aquifers on land, and thus could be replenished by rainfall, said Rob L. Evans, another of the study authors.

“It’s coming from land and leaking offshore,” he said.

Other such aquifers may have been deposited ages ago, when sea levels were far lower and the water from melting glaciers seeped below the exposed land surface.

While some of these glacial deposits may also be connected to aquifers on land, others might not, said Evans, chair of the department of geology and geophysics at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

“If it’s an isolated body, then it’s a one-shot deal,” he said. “If you were to pump it, then it’s gone.”

Evans joined Columbia geophysicist Kerry Key in taking measurements of the deposits off New Jersey and Martha’s Vineyard. Evidence suggests that both are connected to aquifers onshore, and the Martha’s Vineyard offshore deposit may also have been fed by melting glaciers long ago.

The scientists did not measure salinity directly, but used electromagnetic sensors to determine the water’s conductivity. The saltier the water, the better it conducts electricity.

The team took continuous measurements for many miles off the coasts of New Jersey and Massachusetts, finding evidence of freshwater deposits locked in the pores of rocky sediment more than 100 yards beneath the ocean floor.

The scientists cannot say for sure that the underground water systems off New Jersey and New England are connected, but they think it is likely, covering a total area of close to 15,000 square miles.

There Is Water Under the Ocean

Using electromagnetic sensors, scientists have mapped a vast freshwater aquifer beneath the ocean floor off of New Jersey. Evidence suggests it is connected to freshwater aquifers on land and is periodically replenished through underground seepage.

Groundwater experts not involved with the study said the method used by the Columbia-Woods Hole team was a valid way to gauge salinity — especially because the results were consistent with the data from the earlier drilling samples.

Further research is warranted to confirm that the aquifer system actually runs up and down the East Coast, but the initial study is nevertheless valuable, said Vincent Post, a hydrogeologist with the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Germany.

“The present data are already an important step forward in our understanding the offshore groundwater resources,” he said.

As for any potential oil and gas beneath the Atlantic seafloor, that issue is in the news as well. Last year, the Trump administration proposed allowing seismic tests in preparation for possible drilling, but New Jersey and other states have gone to court to block such tests. Then in April, the administration said it would hold off on plans to allow drilling, pending the outcome of a separate legal challenge in federal court.