Thanks to the Phillies, Bryce Harper is the modern-day version of Dr. J | Mike Sielski

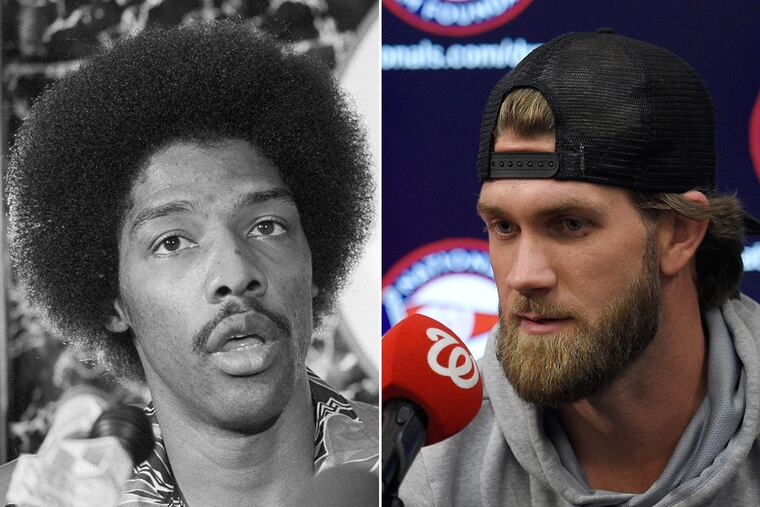

The best historical analogy for the Harper signing happened in 1976, when Julius Erving joined the Sixers.

There is a temptation, a natural one, to suggest that the core of the story that shook Philadelphia on Thursday — Bryce Harper’s decision to sign with the Phillies — is without precedent in the city’s sports history.

Harper arrives having already established himself not merely as one of Major League Baseball’s best players, but as its biggest star at the apex of his abilities, as the face of his sport. That status sets him apart from Pete Rose in 1978 and Jim Thome in 2002 and Cliff Lee in 2010, from the 1992 trade for Eric Lindros, and the 1996 drafting of Allen Iverson.

Each of those athletes was great, but Harper is younger, better, more famous, and/or more established than any of them. He was on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 2009, when appearing there still carried remarkable pop-culture cachet, as a 16-year-old. He was baseball’s LeBron James. He has been named to six All-Star teams, been named the National League rookie of the year and most valuable player. This is as big as it gets, and you have to go back nearly 43 years to find an appropriate comparison.

You have to go back to a man who could fly.

The mystery of Dr. J

Bill Melchionni, out of Bishop Eustace in Pennsauken, out of Villanova University, a rookie on the 1966-67 NBA-champion 76ers, was a month into his new job, as the general manager of the ABA’s New York Nets, when the phone calls about Julius Erving started.

There were two kinds of calls, both born of the same problem: Roy Boe, the Nets’ owner, was moving the franchise to the NBA, and he needed money to pay a territorial fee to the New York Knicks. Erving was Boe’s meal ticket. Three ABA championships, three scoring titles, four MVP awards with the Virginia Squires and the Nets, the perfect Afro, the nickname “Dr. J.,” soaring slam dunks that had to be seen to be believed: Erving was as much myth as man.

So in the fall of ’76, Melchionni began fielding those phone calls. One kind was from NBA executives who wanted to schedule exhibition games against the Nets — and who, Melchionni said, were willing to pay $50,000 per game to do it — because Erving was so great a gate attraction.

The other kind was from NBA executives who wanted Erving to play for their teams.

“Roy felt that being in the NBA was more important than one player, and [coach] Kevin Loughery and I tried to persuade him otherwise,” Melchionni said Friday morning by phone from his winter home in Naples, Fla. “But he was under the impression he could get another player, but he didn’t realize the magnitude of losing somebody like Julius.”

Understand: At the time, the NBA was not the global, billion-dollar behemoth that it is now, and the ABA was even more rag-tag, though its talent pool was nearly as deep. (Ten of the 24 players selected for the 1976 All-Star Game, the first after the leagues merged, had been in the ABA the previous season.)

The ABA had no national-television contract. If the league was lucky, a single playoff game — one that happened to fall on, say, a Sunday afternoon — might be telecast on one of the country’s three networks: ABC, CBS, NBC.

Pro sports still had a small-time feel to it then, particularly a fly-by-the-seat-of-their-short-shorts operation such as the ABA, and there was an element of mystery to it all, especially to Erving and the sequence of events that led him to the Sixers, that 24-hour news and social media have long since eradicated.

“You have to realize the magnitude of what happened,” Melchionni said. “Harper coming to the Phillies is a big deal, but Harper has been exposed across the country.

"With the ABA, everybody thought we were in the hinterlands. We had a lot of really good players people didn’t know, and a lot of people hadn’t seen Doc play throughout the country. All they’d see was snippets of this Julius Erving. So I think it was bigger than Harper coming because everybody’s seen Harper. Everybody’s seen LeBron James. Three-quarters of the country probably never saw Doc.”

Pat Williams, the Sixers’ GM, had. Erving held out of Nets training camp over a contract dispute, and Williams called Melchionni.

“If things ever deteriorate to the point that you have to trade Julius Erving, please let us know,” Williams told him, then hung up and didn’t think more about it. “It was kind of like saying to Raquel Welch’s mother, ‘Hey, if she ever needs a date, here’s my phone number,’ ” Williams and former Inquirer columnist Bill Lyon wrote in their book, We Owed You One! The Uphill Struggle of the Philadelphia 76ers.

Two weeks later, Melchionni called back. Williams went to New York to meet with him and with Irving Weiner, Erving’s agent.

The best of bargains

“We talked about what kind of guy Julius was, would he fit in,” Melchionni said. “I didn’t want to have that conversation because I knew what kind of guy Julius was. I knew what kind of player he was. And I knew he would be a home run for wherever he was going. But Roy Boe said I had to go talk to Pat. Shortly afterward, they made the deal.”

It was a thunderbolt then. It seems so modest now. The Nets agreed to sell Erving to the Sixers for $6 million: $3 million to Boe, $3 million to Erving over a six-year contract.

For an indication of just how much professional sports has changed, just how big the business has gotten, consider: The Phillies and Harper agreed to a 13-year, $330 million contract. Even in 2019 dollars, adjusted for inflation, Erving’s six-year deal would total just $13.3 million. A bargain, in any era, for someone who could walk the sky.