What a poem and an Eagles game may have in common, and a psychiatrist’s unusual prescription in the time of COVID-19

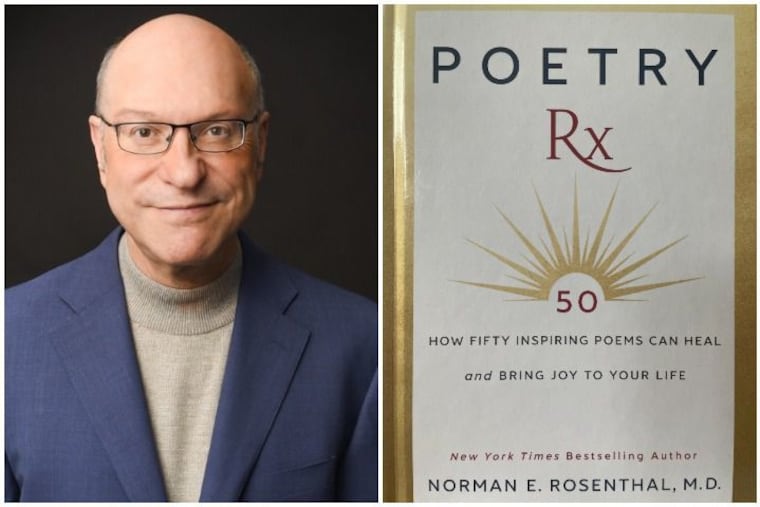

Poetry can stimulate our “reward circuitry,” says psychiatrist Norman Rosenthal, like the sensation we might get from watching a sporting event.

After psychiatrist and author Norman E. Rosenthal moved from his native Johannesburg to New York to begin a residency in 1976, he was shocked by the literal night-and-day differences between the two cities.

In the fall, the rapid loss of light in Gotham, 1,000 miles farther from the equator than his homeland, darkened his mood and sapped his energy. That experience inspired him to identify Seasonal Affective Disorder and pioneer the use of light therapy. He wrote a seminal treatise on SAD, Winter Blues, and subsequent best-selling works.

Rosenthal, affiliated with the National Institute of Health for 20 years, these days is a clinical professor of psychiatry at the Georgetown University Medical Center, maintains a private practice in Maryland, and is still writing.

In his 10th book, Poetry Rx, Rosenthal interprets 50 poems by the likes of William Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Robert Frost to argue for the healing power of verse. He suggests that Eagles fans might want to give it a try, although it’s possible at least some will pass.

To paraphrase the question you raise in your introduction, what qualifies a practicing psychiatrist with no formal literary training to wax expert on the power of poetry?

A major desire I had was to share my love of poetry and explain what it can do for people psychologically. I am not a poetry professor, simply a well-read amateur who loves poetry. I am a seasoned psychiatrist and coach; I can take my knowledge of those fields to help people understand how to read a poem and get the most out of it in terms of what could benefit them, to squeeze the last drop of juice out of the orange.

For a psychiatrist, poetry therapy certainly would qualify as the road less traveled by, to invoke Robert Frost. What made you choose this road?

By nature I have always preferred the road less traveled by. I think you will usually discover more if you don’t go with the crowd. For example when I started my research on Seasonal Affective Disorder, nobody even knew it existed and some people thought it was a joke. It was the road less traveled by, and it’s been one of the best roads I have ever taken.

Can reading a poem actually stimulate that physiological ‘reward circuitry?’ In short, could it effectively act as a natural ‘drug?’

Researchers have found that listening to a poem can actually stimulate goose bumps and alter the reward circuitry in the brain as measured by imaging studies, though perhaps not as much as an exciting Eagles game. … [But] in their own ways, reading a good poem and watching a good game are likely to stimulate our reward circuitry.

You divided your book into five parts. The logic of ‘Into the Night’ as the final one is obvious enough. What was behind the sequence of the first four?

I started with “Loving and Losing” because so much poetry has been written about those powerful experiences, and people seem to gravitate to those kinds of poems, either when they’re in, or out of, love. So it was a natural place to start. Next, so many people are stimulated to write poetry by natural settings. So that was a logical follow up. The third category, “Aspects of the Human Condition,” picks up diverse important topics, such as anger, trauma, and the difficulty of immigration and leaving home. This section also captures positive experiences like the healing power of reconciliation and faith, and the thrill of discovery. The fourth section is one that often arises in maturity — figuring out what constitutes a good life and transmitting that knowledge to the next generation.

Regarding COVID-19, aside from the physical toll and anxieties, from the psychiatric perspective what has been the most damaging consequence of the pandemic?

A recent study found that a full third of people with severe COVID are left with damage to their nervous systems as evidenced by neurological or psychiatric problems. That has the potential to wreak tremendous damage, physically and financially. One little-known fact about depression, for example, is that the World Health Organization has found it to be a leading cause of disability worldwide. The psychological aftermath of COVID can only add to this burden.

If you had to choose a poem that best speaks to what people have been through in the last 13 months, what would it be?

Being asked to choose the best poem is like being asked who is your favorite child. But I would venture the best poem for this particular purpose is “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley. It has inspired millions of people in the harshest and most extreme situations. Nelson Mandela, the great South African leader, memorized it during his long imprisonment on an island fortress and taught it to fellow prisoners. It has been emblazoned on the masthead of the eponymous Invictus Games, established for wounded servicemen. It is a great poem and a great source of inspiration for people when they need it most.