Emma Amos’ artwork is celebrated in a traveling retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

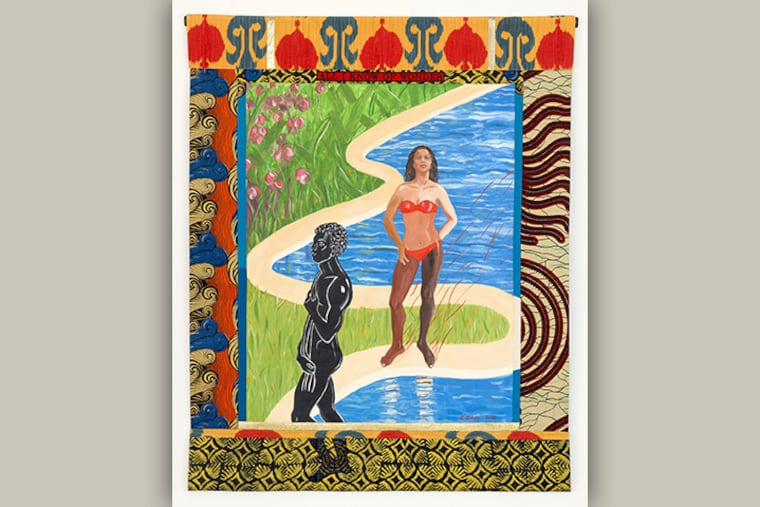

The artist explored race and gender through paintings, weaving, and textiles.

It’s likely that you’ll think of Jasper Johns when you hear mention of an artist born in the South who has created striking paintings of targets and flags and is now the subject of a major exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

And you would not be mistaken.

But there are, in fact, two such artists. Johns, of course, now 91, and among the most celebrated artists of his generation, is one of them. He’s the subject of a huge, two-part exhibition now up at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The second artist on view at the Art Museum is Emma Amos, a Black painter and printmaker from Atlanta, who grew up in a household frequented by W.E.B. DuBois and Zora Neale Hurston, and was a member of feminist and activist art groups like Heresies in the 1970s and the Guerrilla Girls in the 1980s, and Black collectives like Spiral in the 1960s.

She is not as famous as her white, male compatriot, to put it mildly.

In fact, Amos never even had the opportunity to see her work in this current exhibition, her first major solo traveling museum show. She died in May of 2020 at the age of 83 — about a year before “Emma Amos: Color Odyssey” opened at its first venue, the Georgia Museum of Art.

Now “Color Odyssey,” an exhibit of roughly 60 works, has opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art for a run through Jan. 17.

That Amos — creator of a powerful body of work as a painter, printmaker, weaver, and textile designer — had not achieved broad acclaim by the time of her death is attributed to two factors: her gender and her race.

The view that she has been excluded from the painterly club is a consensus that has only formed in the wake of the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements. Nevertheless, it’s safe to say that Amos was more than aware of the issue.

“It’s always been my contention,” she once told an interviewer, “that for me, a Black woman artist, to walk into the studio is a political act.”

Laurel Garber, assistant curator of prints at the Art Museum and author of an essay on Amos in the exhibition catalog, said Amos’ “identity as a Black woman artist seemed to be a factor” in her lack of recognition.

Amos was also a weaver, in addition to her other skills, a craft often seen as one of “the stepchildren of the contemporary art world,” Garber said.

“Weaving has a long history of association with Black makers,” Garber continued. “So it wasn’t just her contemporary practice, but the whole history of that medium” that contributed to her artistic identity.

Shawnya L. Harris, curator of African American and African Diasporic art at the Georgia Museum of Art and organizer of the exhibition, said that for Amos, race was not a straightforward matter,despite the racial simplicities that dominate the art world.

“She had a very sophisticated sensibility about race,” said Harris. “She shows that race is a very fluid construction. It’s not this stable, firm fixed entity that we try to make it out to be. It’s pretty fluid. I mean, she was in an interracial marriage. And, you know, that whole notion of passing comes up in some of her works.”

Amos, said Harris, was also “aware of the fact that, as a Black artist, she was automatically going to be expected to produce more political material, you know, even when she didn’t want to so.”

This was a source of annoyance for Amos who told her friend, the critic Lucy Lippard, that “every time I think about color, it’s a political statement. It would be a luxury to be white and never have to think about it.”

In other words, race exists in the art world for Blackpeople — but not for whites. Yet, returning again and again to representation of Blackness, Amos presents skin tones that are modulated across a range of hues. Race is not so easily captured, pinned down, or maybe even recognizable, she seems to say.

“In the mid-’80s, I noticed that curators from public institutions mostly chose to exhibit paintings of mine showing figures that could be identified as ‘black,’” Amos once wrote. “This pattern made me more determined to use a multicolored mix of skin tones. Every African-American artist, including those whose work is more abstract or who do not paint recognizably ‘black’ figures, has confronted curatorial and editorial definitions of ‘black art’ that both include and exclude works, thus continuing the segregation of images and artists.”

But if race cannot be easily pinned down, the corrosive nature of racism is everywhere in the culture, a point Amos meets head-on with a series of great paintings largely completed in the 1990s. Targets (1992) makes use of a characteristic bull’s-eye target and expands it by including two falling figures. X-Flag (1991) deploys the Confederate flag as a motif. Work Suit (1994) makes startling use of a photo of Lucian Freud’s naked torso topped by Amos’ head. Tightrope (1994) presents the artist with the tools of her trade — brushes and breasts.

These works, plus a number of others painted during Amos’ miraculous 1990s , stand at the heart of the exhibition.

“Someone said once that every 30 years or so, certain ideas resurface and there are these paradigm shifts that occur in culture,” said Harris. “I like to think that it was 30 years before that a lot of the work that is in the exhibition was first exhibited and first created.”

Perhaps Amos “was kind of thinking ahead,” Harris said.

“All these ideas of looking at race, looking at gender, looking at the fluidity of all these categories. We take it for granted now, … but she was thinking about all those ideas way back a long time ago. And so I think its time has rolled around again. And people are revisiting these ideas, even if they use different vocabulary to talk about it.”

“Emma Amos: Color Odyssey” runs through Jan. 17, free in the Morgan and Korman Family Galleries with timed museum admission. The museum is closed Tuesday and Wednesday, open Saturday, Sunday, Monday, and Thursday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Friday from 10 a.m. to 8:45 p.m.