John Cale’s ‘nerd-brother’ Tony Conrad is charming, difficult, and totally worth your effort in a big ICA retrospective

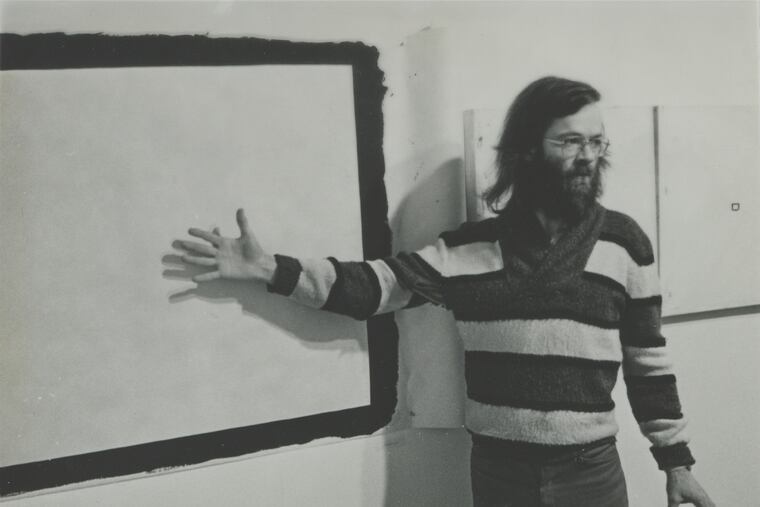

From hippie math prodigy to avuncular professor, Conrad has shaped the music, art, and ideas of the avant-garde.

Tony Conrad wouldn’t have approved of what I am doing right now. One of Conrad’s chief messages is that we shouldn’t let ourselves be manipulated into seeing things as others wish us to see them.

“Introducing Tony Conrad,” at the Institute of Contemporary Art through Aug. 11, is a dense, often rewarding exhibition that resists reviewing. It documents a lifetime exploration of music, film-making, videos, teaching, community activism, and scientific and mathematical thought.

By expressing my point of view, I risk ignoring ways in which you might respond to a difficult, fascinating body of work.

Conrad, who died in 2016, did not exhibit in museums and art galleries until the final decade of his life, but for half a century, he was an influencer, a collaborator, a tinkerer who left his mark in many fields — preeminently in music through his collaborations with La Monte Young, John Cale, and others. In a statement to Rolling Stone after Conrad’s death. Cale called him his “nerd-brother.”

“You don’t know who I am,” Conrad once told an interviewer, “but somehow, indirectly, you have been affected by things I did.”

Among the handful of pieces in the show that were actually made for museum display are a couple of clear glass panels hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the gallery. They have the proportions and much of the presence of paintings. Each has a hole cut into the glass more or less at eye level.

The viewer is invited to look through the eyehole — in other words, to take the traditional fixed position of the viewer in perspective-based western art. But because the glass is clear, it seems silly to use the eyehole. These mute works are an invitation to stop seeing things as we usually do, and to look around at everything.

Although he was part of the New York downtown scene in the 1960s and ’70s, Conrad spent most of his teaching career at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo organized this retrospective.

Though it does provide a comprehensive selection of the works Conrad meant for exhibition, it is at heart an examination of Conrad’s thinking and personality. There are so many videos here, mostly of Conrad talking and demonstrating his works, that you could probably spend a day in the galleries and not see everything.

Conrad was a charmer. He was able to speak engagingly, and even clearly, to all sorts of audiences about how the world works. The show begins with his Invented Acoustical Tools, a selection of broken drums and whimsical, maybe musical, instruments.

They are fun to look at, but they really don’t mean much unless you watch Conrad demonstrate how he used them and recount why he invented them. Most depend on a bow and a loose electric guitar pickup, which he used to get sounds out of almost anything.

The ultimate example is a piece called Quartet, a suspended wooden bench wired for sound. Visitors can sit on it and bang and rub different parts of it to produce a vast range of sounds, many of them striking, few of them pleasant.

In a video later in the exhibition, Conrad pretends to be grading his students’ papers by running his bow along the sides of them. “That one sounds like an A+,” he enthuses, as he bows its edge and produces a deep yet whiny sound. He notes it sounds a bit like the students themselves, asking for better grades.

This is good comedy, but it is also a way to discuss and question the whole idea of standards and where they come from.

In the videos, we see the evolution of Conrad from hippie math prodigy in the 1960s to the avuncular figure of his later years, but there is tremendous consistency in the work. He first became known in the mid-1960s for The Flicker, a radical black-and-white film that consisted solely of frames that were all white or all black, arranged in patterns Conrad developed.

In 1973, he went farther with his Yellow Movie series of paintings, some of which looked like video screens, and others like blank movie screens. There was sound but no obvious visual content. He presented these not as the paintings they literally are, but as very slow movies whose subject is the deterioration of the cheap paint with which they are made.

These works were long unseen, but now it is possible to see that Conrad was right. They have changed over time, though nobody would be patient enough to sit for 46 years and watch how it happened.

This show, and Conrad himself, demand patience. It is not visually seductive. You don’t see it and get it instantly. But if you see it with the kind of playful intensity the artist embodied and encouraged in others, you will be glad you were introduced to Tony Conrad.

An artist to watch … and a series to put on your radar

Also on exhibit at ICA, through March 31, is “Cecilia Vicuña: About to Happen,” the first major U.S. solo exhibition of the artist and poet born in Chile in 1948.

This show, which deserves more attention than I will be able to give it here, at first feels like a visually rich antidote to all the rasping and cogitation going on downstairs. But it soon becomes clear that this work grows from a strong personal vision, a sense of place, and from a narrative of environmental catastrophe and resilience.

Its centerpiece is Balsa Snake Raft to Escape the Flood (2017), which Vicuña made for the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans, where this show originated. The work is made of materials she salvaged from the Mississippi. She posits that reclaiming our trash might be essential to our survival when catastrophe happens.

I was most impressed, though, by the dozens of small sculptures Vicuña calls precarios, which she began making years ago from materials she found on the beach.

These constructions, which seem to be made from bone, stone, used dental floss, and ruffled feathers, among other things, are mostly only a few inches high. But that does not mean they are trivial. Each is a well-considered sculpture.

Some address issues of balance and structure. Others highlight materials. All are the right size, though some could be the seeds of monuments.

A third exhibition, “Mundane Futures,” is the first of three shows in ICA’s yearlong project “Colored People Time.” This first one, which offers more to read than see, runs through March 31. I expect to return as future installments unfold.

ON EXHIBIT

Introducing Tony Conrad, plus Cecilia Vicuña and Mundane Futures

Conrad retrospective through Aug. 11, Vicuña exhibition and “Mundane Futures” through March 31, all at Institute of Contemporary Art, 118 S. 36th St.

Hours: 11 a.m.-8 p.m. Wednesday, 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Thursday-Sunday, closed Monday and Tuesday.

Admission: Free.

Information: 215-898-7108 or icaphila.org.